‘Only $100m?’: Secrets of rich and powerful exposed in the Pandora Papers met with a weary shrug

The revelations are eye-catching, but the test will be whether they lead to major reform, writes Borzou Daragahi

A leak of documents over the weekend showed Azerbaijan’s strongman, Ilham Aliyev, had secretly bought $540m (£400m) worth of property worldwide, including a central London home registered in the name of his then 11-year-old son.

But on the streets of Baku and other cities of the Caucasus nation of 10m, infamous as a kleptocracy, there were shrugs. Azerbaijanis have long been used to the idea of their leader as corrupt, and they now broadly support him for leading a military victory over Armenia in a war last year.

“A majority doesn’t really care about it,” said Arzu Geybulla, journalist and analyst specialising in the Caucasus and Turkey. “I don’t think they’re going to rise up. Not because they don’t care about corruption. Everyone is so used to it. Everyone knows about it. People don’t care because they know there won’t be any punishment.”

In films, the crusading journalist spends 90 minutes exposing corruption before police lead the bad guy away in shackles, just as the credits roll. The real world is never as simple, especially at a time when publics have grown almost immune to official misconduct and dysfunction and often vote for or acquiesce to autocrats appealing to vague notions of national or ethnic pride.

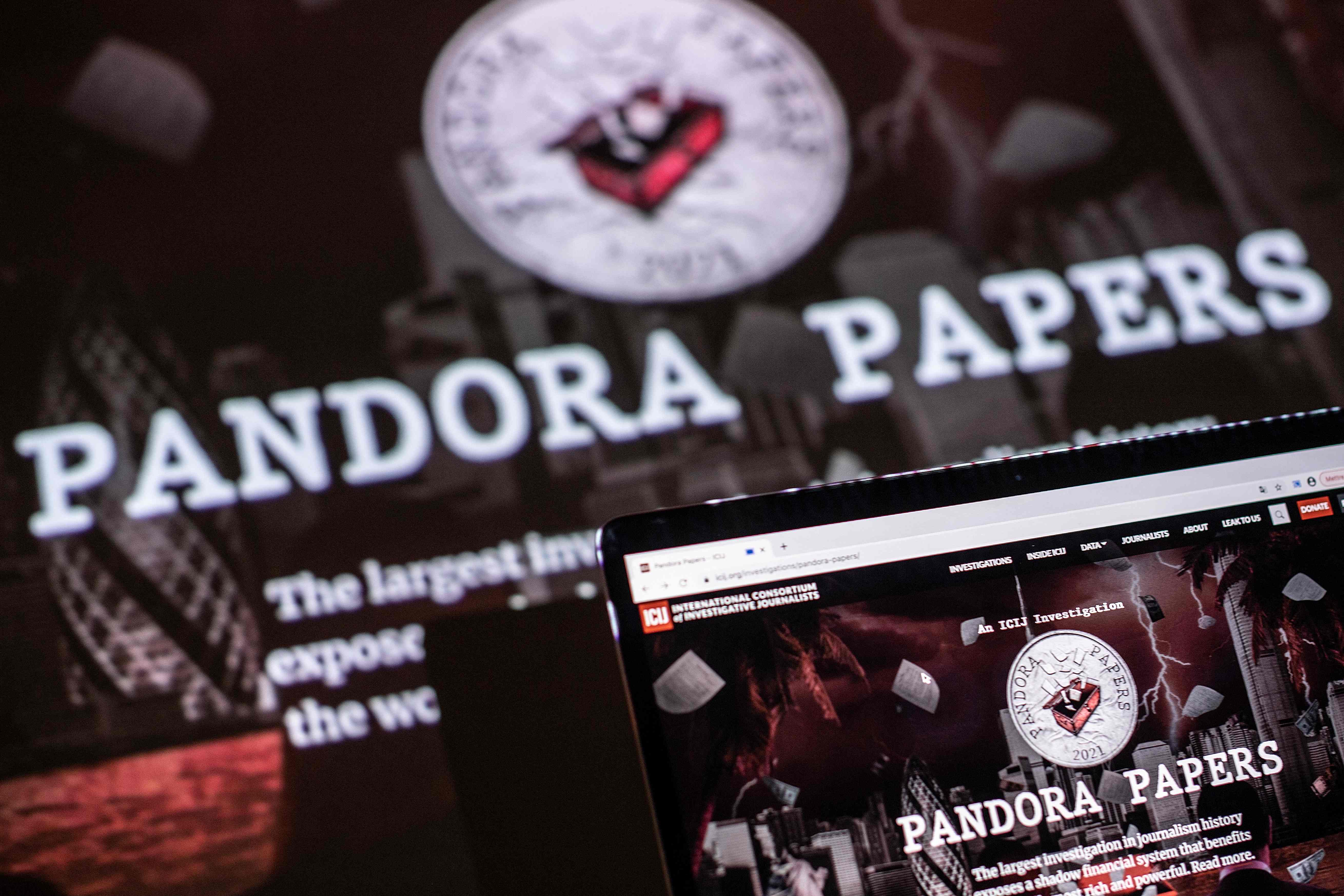

On Sunday, a consortium of journalists and news organisations across the world unveiled the Pandora Papers, a series of reports based on 11.9m leaked documents from more than a dozen private firms that show efforts by politicians and oligarchs worldwide to shield their potentially ill-gotten wealth from the eyes of tax collectors and the public. The trove reveals lavish spending and outrageous attempts to hide loot by the world’s super-rich.

Among the top revelations: Jordan’s King Abdullah secretly bought 14 luxury homes worth $106m; Czech prime minister Andrej Babis, a populist rightwinger currently running for re-election, moved millions through offshore companies to secretly buy an estate on the French Riviera; and members of Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan’s inner circle owned companies and trusts worth millions of dollars.

King Abdullah called the claims “defamatory and designed to target Jordan’s reputation”. Babis protested his innocence on television on Sunday night, and Khan that any “wrongdoing” would be investigated.

But like the Panama Papers, a smaller 2016 leak of documents from one firm in Panama City, it is doubtful whether any of it will spark political change or reform.

“Right now as a citizen you’re worried about climate change, Covid, food prices – corruption is still seen as one issue out of many,” says Max Heywood, of Elucidate, a Berlin-based risk-management firm specialising in financial crime. “This is perhaps the critical issue that links to others. But that message hasn’t broken through.”

One Jordanian journalist said people in Amman were shrugging over the revelations about their king, whom they have long dubbed Ali Baba. “Only $100m?” joked one Jordanian.

Like the Panama Papers, the Pandora leak exposes a parallel financial system of accountants, lawyers and financial planners who use legal loopholes and accounts in sketchy offshore havens to hide wealth and lavish purchases.

Even more than the Panama Papers, the latest leak shows how powerful leaders and politicians often purporting to be anti-corruption figures avail themselves of these mechanisms. For example, Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, a former comedian who campaigned as an anti-corruption crusader, showed up in the Pandora leaks as a co-owner of a firm that took advantage of the offshore banking system.

Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyatta, who has also campaigned on anti-corruption credentials, has allegedly amassed $30m of offshore wealth. He said he would “respond comprehensively” to the allegations in time.

Hiding wealth and getting around the “know your customer” rules established by banks in the wake of the Panama Papers and other scandals is expensive and complicated. Yet the tools to circumvent them still exist, and providing them has become a sort of business model for a kaleidoscope of financial services, lawyers and consulting firms.

Revelations that this world of tax havens, offshore accounts, obscured ownership records and blind trusts live on despite the legal changes and political reforms of recent years add to the sense of hopelessness.

“Many politicians campaigning on anti-corruption platforms are the ones using the system,” says Maira Martini, an anti-money-laundering specialist at the anti-corruption advocacy group Transparency International. “You have a powerful lobby of people who benefit from the status quo. How can we expect them to change the rules?”

Where reform may be possible is in the west, which emerged in the Pandora Papers as the major conduit for facilitating the hiding of wealth and laundering proceeds through property investments. Among the top addresses for the secretive trusts and accounts were US states with lax laws such as South Dakota and Nevada, which are used by oligarchs and human-rights abusers to hide wealth. Property in wealthy enclaves such as London and Southern California are among the top receptacles for laundered money.

“We see real-estate prices increasing and we see threats to democracy and the rule of law in the west,” says Ms Martini. “I hope this creates the momentum that is necessary.”

Fighting corruption is one of the pillars of the much-vaunted Summit for Democracies planned by the administration of US President Joe Biden in December. Among policymakers, scholars and journalists, there is a growing consensus on the need to check the rising power and abuses of an elite class of super-rich and powerful who undermine democratic norms.

“Across the globe, weak state capacity, tenuous rule of law, high inequality and corruption continue to erode democracy,” said a White House statement about the 9 December summit.

“What I hope is that some changes are already in motion,” says Heywood. “There are openings and venues and things are moving forward.”

But Biden himself is a beneficiary of the parallel system, even if he doesn’t necessarily partake in it. Before becoming vice-president in 2008, he was a senator in the state of Delaware, infamous as a place where corporations and trusts from around the world registered to avoid the scrutiny of regulators and tax authorities. Securities, investment and financial firms have donated $25m in political contributions to Biden since 1989. Lawyers and law firms, which also play a role in hiding wealth, kicked in another $61m, according to Open Secrets, a website that tracks American political money.

“It’s very difficult to mobilise people because there’s so much cynicism and apathy,” says Ms Martini. “It’s like, ‘Don’t tell me again that my politician is hiding money’.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks