Britain ignored genocide threat in Rwanda

Documents declassified 20 years on show the UK and US were warned of a 'new bloodbath'

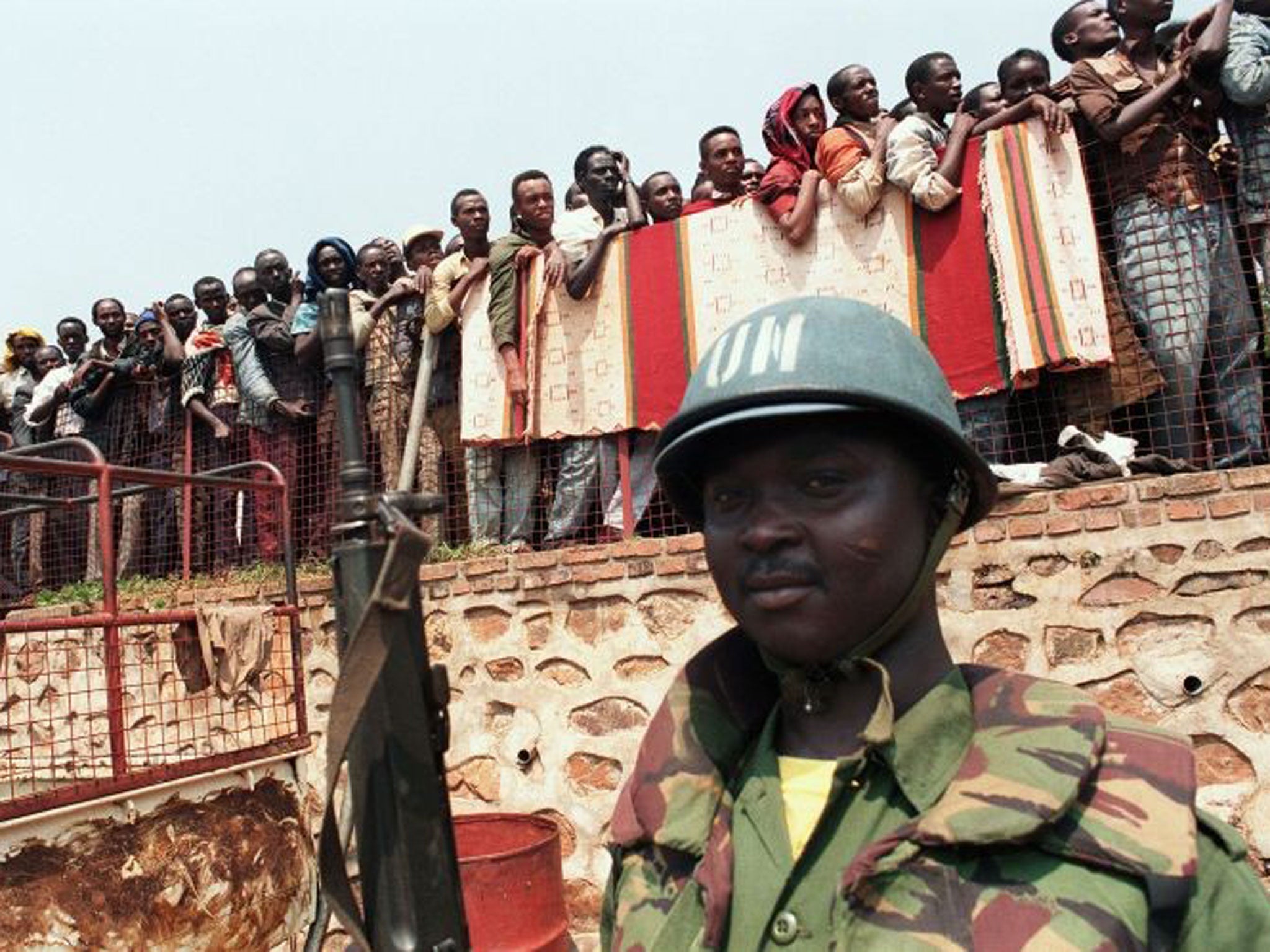

It was an unparalleled modern genocide, an attempt to exterminate an entire people in 100 days. And in the years that followed the killing of some 800,000 Rwandans in 1994, political leaders have expressed their regret at an international failure to stop the violence.

Bill Clinton, United States president at the time, admitted last year that if the West had intervened earlier to stop the killing, mostly by Hutus against Tutsis, 300,000 lives could have been saved.

The violence began with the killing of Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, when his plane was shot down above Kigali airport on 6 April. Within hours, violence spread from the capital across the country, and did not subside until three months later.

Ahead of the 20th anniversary of the genocide, last week declassified diplomatic cables were released by the National Security Archive at George Washington University which showed that the US, Britain and the United Nations were explicitly warned that a "new bloodbath" was imminent in Rwanda.

Rather than increasing the power of the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (Unamir), the governments of John Major in Britain and President Clinton in the US were considering rowing back the peacekeeping effort, according to the cables.

The diplomatic messages showed that on 25 February 1994, the Belgian foreign ministry had expressed "alarm" at the worsening security situation in Kigali. Lode Willems, the Belgian ministry's chief of staff, wrote to Paul Noterdaeme, the country's ambassador to the UN, describing Rwanda's "significant deterioration" and asking for greater UN powers to act. The UN mission in the country could not "firmly maintain public order" and had "a serious credibility problem", Willems added.

But in reply Noterdaeme said that both the US and UK were opposed to action. "Not only are the United States and the United Kingdom against it, they may even, according to their delegations, withdraw Unamir altogether in case of difficulties... There is a financial logic behind this: the United States never wanted more than 500 men for Unamir," wrote Noterdaeme. The UN, he added, was against intervention in the former Belgian colony and "not inclined to adjust the rules of engagement".

Three months after the cables were sent, in May, UN members agreed to increase the contingent of troops to 5,000. They were not deployed for a further six months – by which time the killing had already stopped.

While John Major defended his decision not to send troops to Rwanda – he told MPs in July 1994 it was "simply not practicable" for the UN Security Council to become the "policeman of every part of the world" – Mr Clinton was apologetic on a visit to the country in 1998. "We did not act quickly enough after the killing began," he said.

"We should not have allowed the refugee camps to become safe havens for the killers. We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide." Next month a series of events will be held to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the genocide. Kwibuka20, translated as "remember20" asks the world to ensure that "such an atrocity can never happen again".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks