The Big Question: What is the Commonwealth's role, and is it relevant to global politics?

Why are we asking this now?

In an international calendar full to bursting with uncomfortable acronyms it's time for one of the worst of them: CHOGM. The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting convenes in Trinidad and Tobago tomorrow for its bi-annual get together, which can ordinarily be counted upon to be in one of the warmer member states. Last time it was Uganda.

The agenda this year is dominated by the expected acceptance of Rwanda into the fold, something which nations such as Britain, Australia, Canada and Uganda have lobbied hard for. Those less happy with the newcomer to the club are the agencies that have examined Rwanda's troubled record on human rights and found it wanting. They have lobbied against the central African country's acceptance.

What exactly is the Commonwealth?

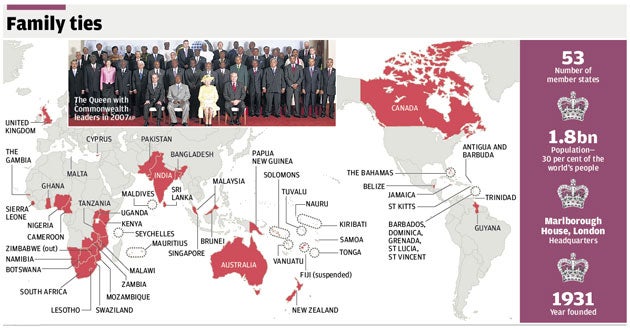

That depends, both on who is asking and who is answering. Formerly the "British Commonwealth", the modern version came into being 50 years ago, shedding the British part of its tag and becoming the Commonwealth of Nations. The old club of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa has since swollen to 54 countries, until it lost Zimbabwe, and is expected to return to that number during the coming weekend.

To its supporters it is a British foreign policy success story that has come to encompass every region, religion and race on the planet, something no other organistation apart from the UN can boast. It enables otherwise isolated and impoverished nations to network with powerful allies and be, in the words of one booster, "a decent club... which confers a sense of identity... no more no less." While its membership is almost entirely made up of English-speaking former colonies that share a legal system and often a constitutional framework, Britain is no longer dominant in what is a voluntary association.

Are there any dissenters?

Yes. Many. Some see the Commonwealth as a peculiarly British consolation prize for the loss of Empire, that bolsters the UK's sense of importance while doing almost nothing else. A collection of not very important states brought together by the unhappy accident of having been colonised by the English.

It talks in high ideals but trades in a much more compromised reality, offering abusive regimes a fig-leaf of legitimacy and a platform that they would otherwise have to look for at the more crowded but equally grubby UN. Considering that it confers no trade priveleges, has no influence on defence or economic policy, no executive authority and no sensible budget to play a global role it remains a talking shop at best and at worst a costly junket. The countries that can would be better served by spending their time and money on organisations like Nato, the UN or trade blocs like the European Union.

Does anyone else want to join and, if so, why?

Yes they do. In fact, there's a queue. Sitting behind expectant Rwanda are Madagascar, Yemen, Algeria and Sudan. Previous unsuccessful suitors have included Cambodia and Palestine, while those with an appetite for being shouted at have even suggested this year that Ireland might rejoin.

As to why – there are several suggestions, and different aspirants offer differing explanations. Meetings like CHOGM give smaller nations the chance to lobby for bi-lateral trade deals, to influence the positions of bigger powers at forums with real bite like the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Its formal and informal channels benefit the little guy, something that Guyana demonstrated when it floated its offer to protect the entirety of its standing forest in return for development aid on the sidelines of the Uganda meeting in 2007. Britain, eventually, declined but the idea got media coverage and Norway took them up on it this month to the tune of $250m.

Are those the only reasons?

Not exactly. A second look at the list suggests some worrying truths. Nations like Sudan, Yemen and to a lesser extent Madagascar may well like the Commonwealth precisely because it doesn't have the power to enforce international norms and has to rely on "constructive engagement" - a staple of regime's from Khartoum to Pyongyang in North Korea. A talking shop which offers access to development aid and informal trade talks while conferring prestige and an international platform is hard to dislike. Let's not forget it also offers access to the Commonwealth Games, an international sporting event where the competition is so modest that even the UK can expect a decent medal haul and which was memorably introduced by the sports writer Frank Keating as "a bucketload of pointless contrivance."

Which high ideals does the Commonwealth espouse?

On the tin it says that the grouping is about promoting democracy, good governance, human rights and prosperity. The Harare declaration in 1991 is billed as the Commonwealth's core set of principles and values. Those include: world peace, economic development, the rule of law, a narrowing of the wealth gap, an end to racial discrimination, liberty regardless of race or creed and the "inalienable right to free democratic processes".

The setting for this declaration could hardly be more poignant. Since 1991 Zimbabwe's life expectancy has imploded, the regime has stoked vicious racial politics, collapsed the economy and stolen elections. The reaction of the high-minded Commonwealth was labelled "spineless" in 2002 by this newspaper, as it dithered over ejecting Robert Mugabe's government, which walked out by itself the following year. Since then it has, in the words of the eminent constitutional expert Yashpal Ghai, "looked desperately for ways of doing nothing" about a host of crises. And only reluctantly suspended Pakistan, twice, and Fiji, once. Professor Ghai's assessment is that the grouping "couldn't care less about human rights".

What about the Queen?

All this leaves Her Majesty on a plane to Trinidad and Tobago, where she will attend to the latest CHOGM with typical seriousness. This despite 33 of her family of nations being republics, five having their own monarchs and only the remainder having her as their head of state. Of them, Australia and Canada now openly debate and ocassionally vote on whether they still want Elizabeth II. When looking for a reason why the Republic of Ireland will not rejoin one need look no further, and it's hard to see Omar al-Bashir of Sudan rewriting the constitution in order to curry favour.

Does the Commonwealth still matter?

Yes...

* The Commonwealth provides a space where big and small nations can speak as equals

* It's a voluntary association and if it wasn't performing properly there wouldn't be a queue to join

* It encourages developing members to raise their standard of democracy, rights and governance

No...

* It talks about ideals that it doesn't uphold and offers a fig-leaf of legitimacy to damaging regimes

* It wastes the time of governments that would be better spent on regional trade blocs and pacts that matter

* Once every four years it provides England with the false impression that it can win things in the sporting arena

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks