The man in the room: Mikhail Gorbachev’s translator says Russia will come to appreciate last Soviet leader’s legacy

Seen but rarely heard. Moustachioed Pavel Palazhchenko was the man who saw the end of the Cold War from close up and makes his voice heard in a new book, reports Oliver Carroll in Moscow

Next year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Soviet Union, a shift remarkable not only for its momentousness as the relative lack of bloodshed that accompanied it. That fifteen republics and the Soviet bloc were calmly allowed to go their own ways was the one undeniable achievement of the time — and of Mikhail Gorbachev in particular.

But the late Soviet era and beyond was little fun for most of those living through it, and that has made the 90-year-old Gorbachev a popular target for populists all throughout Russia’s post-Soviet history. Those closest to him admit they are not looking forward to seeing how the current elite will decide to spin the anniversary.

Pavel Palazhchenko, for six breathtaking years from 1985 to 1991 Mikhail Gorbachev’s trusty translator sidekick, says the broad domestic criticism of the former leader comes mostly from ignorance. There were plenty of mistakes, he says, and Gorbachev admits to most himself, but it was “absurd” to blame him for so much that has gone wrong since.

“Making him a scapegoat 30 years on, when presidents have had plenty of time to do things differently, is mad,” he tells The Independent. ”But the lack of appreciation for what he did is not his problem, it’s Russia’s.”

Few men are better placed to reflect on the metamorphoses of late twentieth history as Mr Palazhchenko. From modest beginnings in the Moscow region — he was drawn to the English language by his teacher mother and a love of The Beatles — the high-level interpreter was for a while one of the most recognisable Soviet faces in the West.

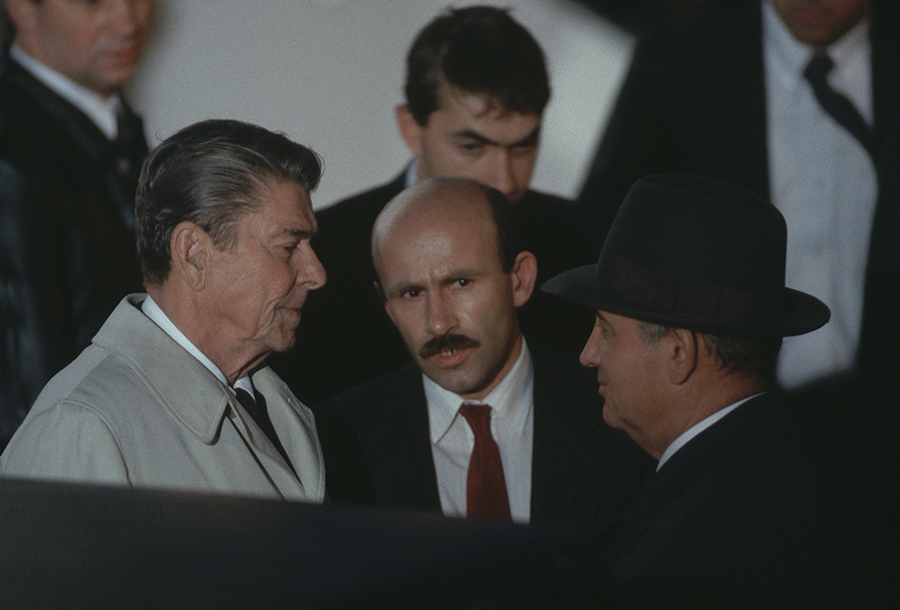

Palazhchenko, with trademark translators’ stoop, moustache, balding head and dark suit, was a fixture behind the giants of the era: Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, George H.W Bush, Helmut Kohl. Many of those historical figures are now dead — the 90-year-old “fighter” Gorbachev is a notable exception — but are reanimated on the pages of Mr Palazhchenko’s new memoirs, “Time and the profession”, published in Russian earlier in December.

Those reflections piece together the interpreter’s life from boyhood to the Cold War summits between Reagan and Gorbachev in Geneva (1985) and Reyjkaviik (1986) that opened the path to massive arms reduction treaties.

They recall many forgotten positions from the time: how Margaret Thatcher, for example, was instinctually against the reunification of Germany. (She feared the change would be “too much for Central and Eastern Europe,” recalls Mr Palazhchenko, and a newly powerful Germany “detrimental” to UK interests on the continent.)

The former diplomat, who admits to having conflicting opinions about the “larger than life” British leader, says the union between Thatcher and Gorbachev was one of the major dynamos of the era. The right-wing prime minister was early in understanding Gorbachev was a new type of Soviet leader, he says: “They hit it off despite being philosophically, very, very different people. There was never any personal tension between them, and Margaret Thatcher more than others believed Gorbachev was for real.”

Thatcher lent a supportive voice even in retirement. She was especially critical about the lack of support sent Mikhail Gorbachev’s way in difficult weeks following the July 1991 G7 meeting. Her intuition certainly wasn’t wrong: a month later came an attempted coup by military hardliners, after which the Perestroika reformer’s position became untenable.

“Thatcher was right the West could have done more to help,” recalls Palazhchenko. “But frankly not much more, since the roots and the problems were mostly domestic in making.”

The man-in-the-room’s account also sheds light on another important matter of Soviet-West relations: NATO expansion. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has regularly seized on a promise supposedly given by the United States to the Soviet leadership not to push NATO membership eastward. For Mr Putin, it is a reason for his citizens to be wary of the West. According to Palazhchenko, he is, “for whatever reason,” mistaken.

The former Soviet diplomat says there certainly was a promise, delivered by James Baker, the US Secretary of State under George H. W. Bush, but that promise only concerned the neutrality of East Germany. The Americans kept their side of the deal, he added, shielding the former Soviet bloc country from major military installation and nuclear weapons.

“It’s simply impossible that Eastern Europe would have been discussed in similar terms,” the interpreter says. “That would have meant amending the North Atlantic Treaty, which says that NATO is an open organisation.”

Mr Palazhchenko says he is sure those pushing the messages today understand that reality. He is far too diplomatic to accuse them of hypocrisy, but hints at the underlying differences of worldview. Relations between Gorbachev and Putin are complicated, if “mutually respectful”.

“Gorbachev has been quite open about his positions on the current international position of Russia,” the interpreter says. It was “no secret” his former boss lamented the lack of trust between the US and Russia. Or that things are unlikely to improve soon given the well-known animosity between Vladimir Putin and incoming US president Joe Biden. Not to mention the fallout from opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s apparent state-sponsored poisoning.

But the undeniable tensions did not mean the two strategic superpowers would be unable to find mutual ground, says Palazhchenko. There were “obvious areas of cooperation in the strategic sphere,” and there was still “a year or two” left to save the main framework of Cold War stability that he helped negotiate.

The first step would be to extend the new START strategic arms reduction treaty, which expires in February, and then negotiate its successor. The INF treaty, concerning shorter range nukes, rejected by the Trump administration last year, could also be “revived” in some form given will on both sides.

“The idea of a world without nuclear weapons is not popular now either in the U.S. administration and the Russian government,” Palazhchenko says. “But if you look at things that have been done already and that's the enormous reduction in the number of nuclear weapons, particularly the number of deployed nuclear weapons, the direction of travel is still there.”

Mr Palazhchenko said it was not idealistic to think that the lessons of the Gorbachev era could be picked up by future politicians.

“It was no easy time for Gorbachev, or any of the people who worked with him,” he says, recalling his boss’s agonising final days before his resignation on Christmas Day, 1991. “But I think that under the circumstances, Gorbachev behaved with great dignity.”

Would the next transfer of power be marked with the same stateliness?

“That I do not know,” he says, “and I certainly don’t know if I’ll see it in my lifetime.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks