Starmer’s Beijing test: Free Jimmy Lai, not chase Xi’s empty promises

China’s most feared critic and a British citizen, Lai has now spent more than five years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement. As Keir Starmer heads to Beijing, securing the media tycoon’s release would show that UK influence still matters in an age of authoritarian power, says Mark L Clifford

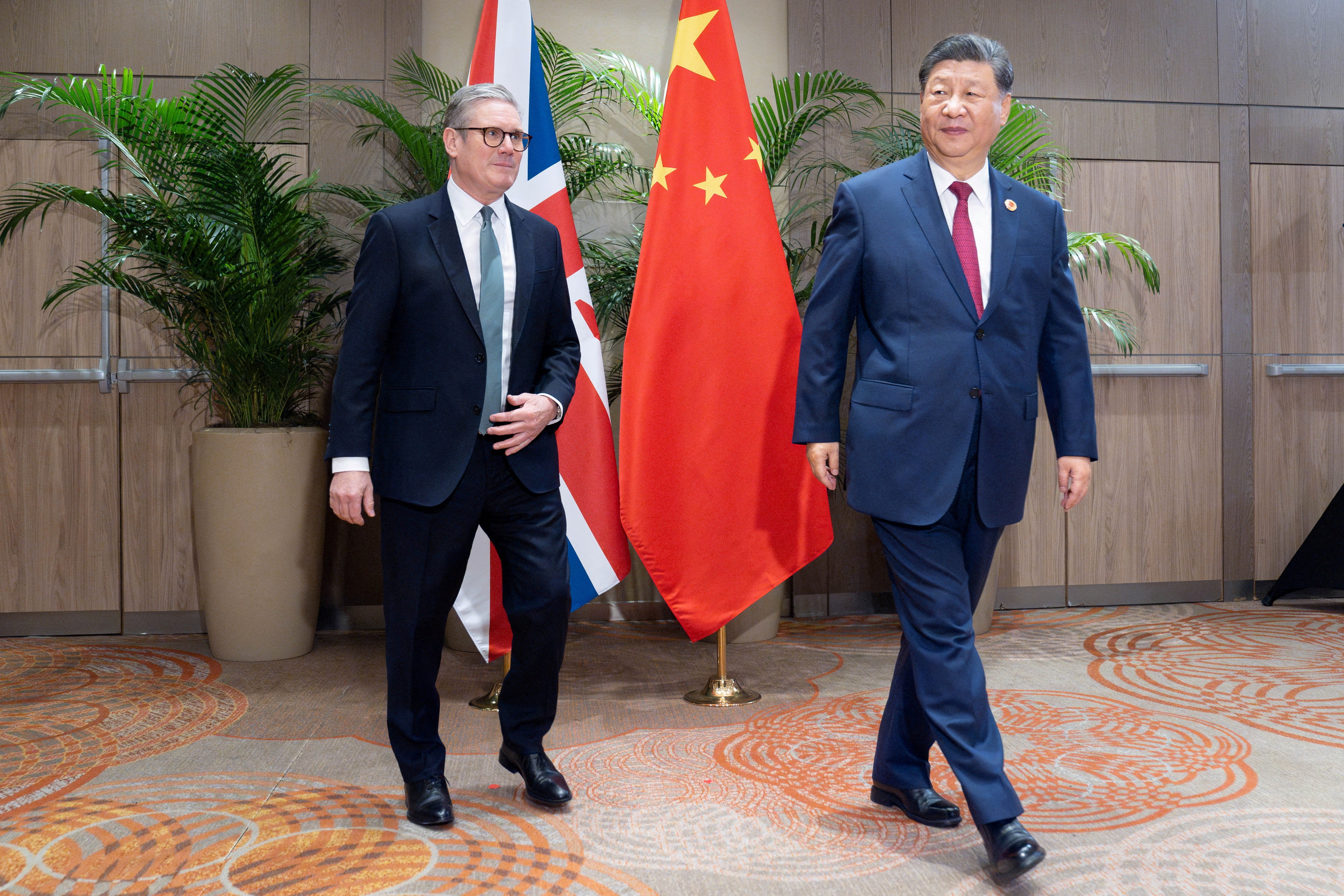

Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping has rewarded Keir Starmer’s approval of China’s “mega embassy” with an eagerly sought trip to Beijing. British officials hope for a renewal of the “golden era” of Sino-British ties of the 2010s, and a slew of CEOs will accompany the prime minister. We can add Starmer to the long line of PMs who nurse the fantasy that a sputtering China – a tiny trade partner – can help pull their economy out of its slump. Expect him to come back with a list of promised trade and investment pledges that will, in the end, amount to much ado about very little.

Using his time in Beijing to get British citizen Jimmy Lai out of the Hong Kong prison, where he’s been languishing in solitary confinement for most of the more than five years that he’s been held, would be a far more concrete accomplishment. That would build on Starmer’s background as a human rights lawyer and burnish Britain’s reputation as a fighter for freedom. At a time when the world faces an authoritarian onslaught, securing the freedom of Lai would send a strong signal that British values and influence still pack a punch.

At 78 years old, China’s most famous political prisoner could spend the rest of his life in jail following a verdict last month by a trio of hand-picked Hong Kong national security judges who found that he colluded with “foreign forces” and published seditious articles.

There’s a strong British connection to Lai’s conviction. The list of those with whom Lai supposedly illegally colluded reads like a who’s who of Anglo-American politics – Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo, John Bolton, Chris Patten, David Alton, Iain Duncan Smith, Luke de Pulford, Benedict Rogers, and Bill Browder. The verdict cited human rights activist and writer Rogers alone 93 times.

The judges denied Lai his right to trial by jury – perhaps worried that he would have been found innocent by a panel of ordinary Hong Kongers who weren’t squeezed by Beijing. They even scotched his choice of lawyer, British human rights barrister Tim Owens, leaving the newspaperman dependent on a team of cowed local attorneys.

Lai’s guilty verdict totalled 855 pages – a doorstop that tried to make up in length what it lacked in substance. The reasoning behind the decision amounted to little more than a cut-and-paste job reprising much of the testimony during the marathon 156-day trial. Prosecutors showed only that Lai was an energetic newspaper proprietor pushing China to make good on its promises for a democratic Hong Kong. The judges decided that his activities and the articles were criminal.

Lai exemplifies Hong Kong freedom. Arriving in the city as a penniless 12-year-old, he first slept on a factory floor. Fifteen years later, he owned a factory, a sweater manufacturer that quickly became Hong Kong’s largest. Bored with making clothes, he started selling them, jump-starting the idea of fast fashion with his Giordano retail clothing chain.

The Tiananmen Square killings of 1989 spurred Lai to switch from the rag trade to the media. Despite knowing nothing about the business, he founded a magazine and then the Apple Daily newspaper. The wildly popular paper peddled a radical brand of freedom – economic and political – wrapped in sizzle and scandal. A self-described troublemaker, Lai made no secret of his distaste for the Chinese Communist Party or his love for Hong Kong.

That distaste is the real reason why he’s in jail. He sits in solitary confinement because he wants to rid China of the Communist Party. He was too rich, and his paper too popular, for the Leninist thugs in Beijing.

Lai and his publications channelled and amplified the aspirations of the Hong Kong people for freedom and democracy. A Catholic convert and a devout apostle of non-violence, Lai is no firebrand. Many young Hong Kong radicals saw him as too conservative, a holdover from a polite play-by-the-rules generation that they believed had accomplished nothing.

Lai could have left Hong Kong before his arrest. He’s been a British citizen for more than three decades and has a home in London. He wasn’t looking to take a position of political leadership. But he wanted to keep speaking truth to power, and so he camped out in the Admiralty district during the 79 days of the 2014 Occupy movement, offering himself up for arrest at the end. As he once told a colleague, he “would rather be hanging from a lamp post in Central [Hong Kong’s financial district] than give the Chinese communists the satisfaction of saying that he had run away”. He hasn’t been strung up, but most of his nearly 2,000 days in captivity have been spent alone, in a windowless cell.

Lai’s fate is about much more than one man. He stands as a symbol for the suffering China can inflict on those it wants to crush, no matter how rich or well connected they are. If we can do this to Lai, is the not-so-subtle text, imagine what we can do to you or your family. That demonstration of brute Chinese state force, of thuggery, is exactly the point.

Lai’s trial and conviction underscore China’s lack of trustworthiness. China vowed that Hong Kong’s people would be able to keep their freedoms for 50 years after the end of British rule. Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping famously quipped that “horses will still run, stocks will still sizzle, dancers will still dance” after the 1997 Chinese takeover.

Beijing offered more than vague phrases of horse racing and dancing to back up its promises. It signed the sweeping Sino-British Joint Agreement in 1984 detailing post-handover arrangements, an international treaty lodged at the United Nations. China followed that up with the Basic Law, a mini-constitution promulgated in 1990. Both promised all manner of freedom – freedom of the press, of assembly and many more. These vows turned out to be meaningless.

China wants to be taken seriously as a responsible global stakeholder. Yet China has broken promise after promise made to Britain and the people of Hong Kong in the run-up to the handover. On the 20th anniversary of the handover, China’s foreign ministry dismissed the Sino-British treaty as a “historical document” that had “no practical significance.” In other words, we got what we wanted, so leave us alone. China’s pledges are the sort of lies teenagers throw out to buy time and hope they won’t be held to account.

I’ve known Lai for more than three decades, since shortly after I moved to Hong Kong in 1992. Both of us believed in the liberalising power of freer markets, convinced that more economic openness would lead to political liberalisation, as it had in South Korea and Taiwan. It didn’t. Or at least, it hasn’t.

We need to be blunt about the threat China poses to freedom everywhere. In the United Kingdom, peaceful pro-democracy Hong Kong activists, like my colleague Chloe Cheung, have bounties on them – £100,000 (HK$1m) for anyone who helps bring about their arrest and prosecution. They are targets simply for free speech advocacy here in Britain. Yet that is tolerated by the British, with little more than a perfunctory protest from the government.

The Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in London, set up to promote trade and investment opportunities, has morphed into a spy nest. Staff have harassed and spied on British activists. A trial set for March may bring more information about this Hong Kong skulduggery in Britain.

Jimmy Lai matters for his own sake, but he symbolises something more. By fighting for Jimmy Lai, we fight for democracy. By securing Jimmy Lai’s freedom, Keir Starmer has a chance to advance the cause of freedom everywhere.

Mark L Clifford is the author of ‘The Troublemaker: How Jimmy Lai Became a Billionaire, Hong Kong’s Greatest Dissident and China’s Most Feared Critic’. He is president of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks