The cases that never quite close

This week the FBI gave up on the DB Cooper case, and we remembered Peter Falconio. A thriller writer explains the interest in crime’s loose ends

Imagine being trapped. Walls of steel and concrete surround you. No one hears your frantic screams or pounding against the locked door. You’re there, imprisoned, no escape, for a year, a decade, maybe two, until you wonder if you’ve gone insane. You start to imagine the unimaginable, that maybe the rest of the world is right and you’re wrong, maybe you really are guilty.

“No,” you tell yourself, clinging to the most fragile thread of hope. “No. I’m innocent. Somehow, some way, someday I’ll prove that. But how can I, when I’m locked away, with no one who believes me?”

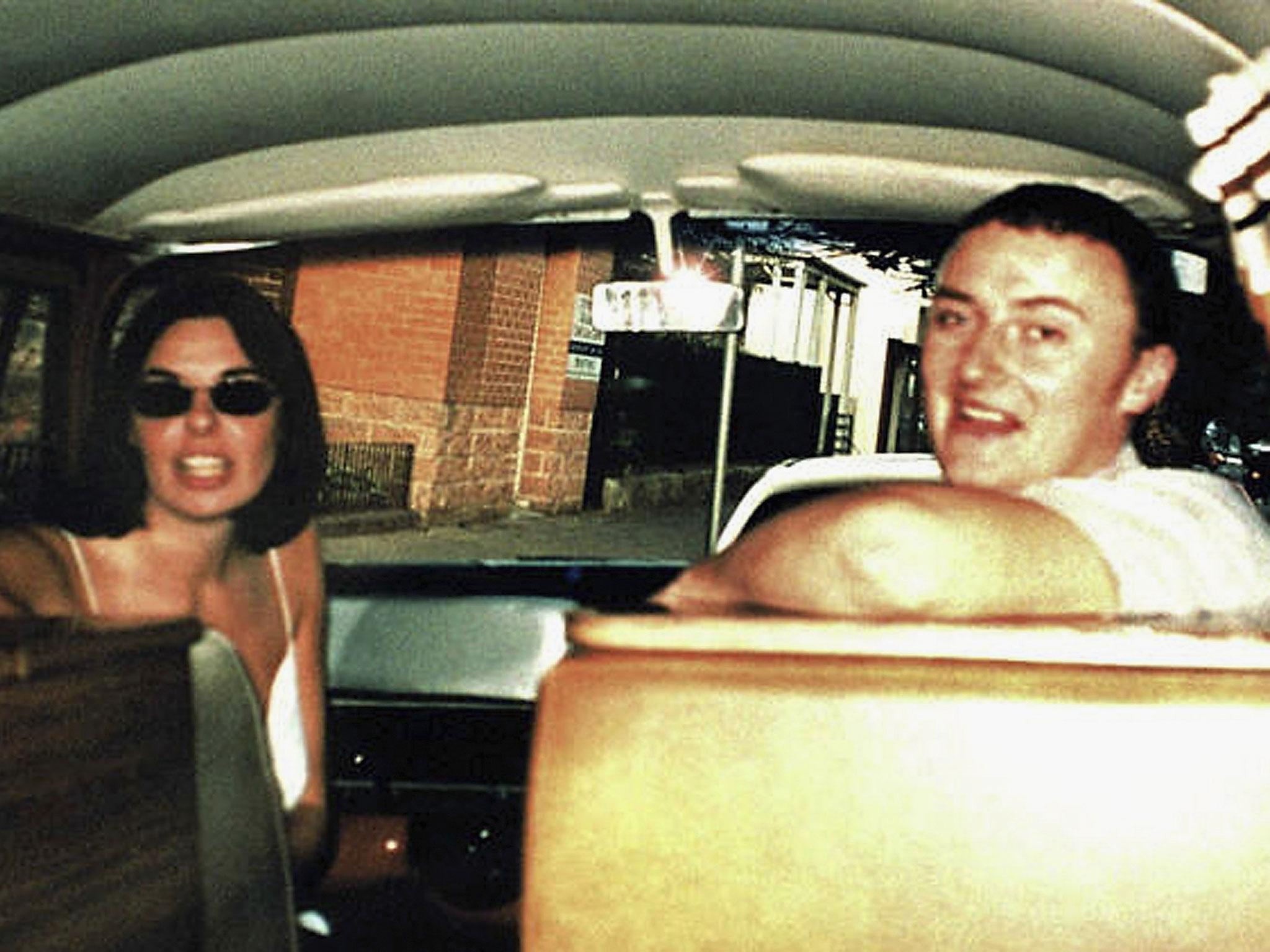

The exploration of cold cases – in fiction, on TV, and in docu-dramas such as Making a Murderer, Serial and The Jinx – has become wildly popular. But it’s important to remember that many of these cases are not cold. Nor are they closed. Not to the prisoners serving sentences for crimes they did not commit, nor the families searching for lost loved ones, nor those who “get away with murder”. That’s why we get a jolt every time the media reminds us, as happened this week with DB Cooper, whose case the FBI dropped after 45 years; or with Peter Falconio, the British backpacker whose disappearance in the Australian Outback had its 15th anniversary this week. (A vagrant was found guilty of his murder, but his body has never been found.)

As a society, we have a vested interest in controlling chaos, serving justice and keeping citizens protected. Unsolved crimes and wrong convictions upset this delicate balance – which is frightening, yes – but we revel in the knowledge that “it could never happen to us” and sleep soundly once we turn off the TV. So here are a few facts about wrongful convictions that might interrupt your slumbers.

According to studies reported by The Economist, psychologists have been able to elicit false confessions from 50-80 per cent of innocent participants – normal university students with no history of mental illness. And in the US, research based on the National Registry of Exonerations reported in 2013 that “for homicide exonerations, the leading cause of false conviction is perjury or false accusations, mostly deliberate misidentifications. Homicide cases also include a high rate of official misconduct, and 74 per cent of all false confessions in the database.” They also found that false confessions are most common from those less than 18 years old and those with any history of mental illness – including the very commonly diagnosed attention deficit disorder, or ADD.

I based a recent novel on several actual cases here in the US, where suspects gave police false confessions but were decades later proven innocent. A variety of factors played a role – sleep deprivation, fear of receiving a worse sentence or being charged with a more serious crime – but some subjects simply surrendered, believing the police’s case was so strong that there was no chance of fighting it with the truth.

That was unsettling. But another type of cold case – missing persons – can be even more unsettling, especially for the families left behind. It’s a parent’s greatest fear. Your child, walking home from school, vanishes. Gone a day, a week, a year, a decade, maybe two, and life as you know it becomes a mockery of what it once was. You learn to plaster a false smile and to nod politely as others talk about their children’s accomplishments. You turn away before anyone can ask you if you have children of your own. You did. You do. Language fails you. Because “missing” has no tense. It’s always present. A life sentence with little hope of escape. Just like the wrongly convicted.

It’s an awful condition for these people to be in – a tragedy – and it’s scary that there are undiscovered criminals in our midst. But from perspective of thriller writers, it’s not all bad: real-life stories not only allow us to bring imaginative closure to such travesties but also perhaps to empower and educate audiences about the truth behind the fiction.

CJ Lyons’ new Lucy Guardino book ‘Devil Smoke’ (Canelo, £3.99) is published on 25 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks