Why Judas Iscariot may actually have been more of a saint than a sinner

Perhaps we could cut Iscariot a little slack – because if the Bible isn’t clear on his character, then how can we be?

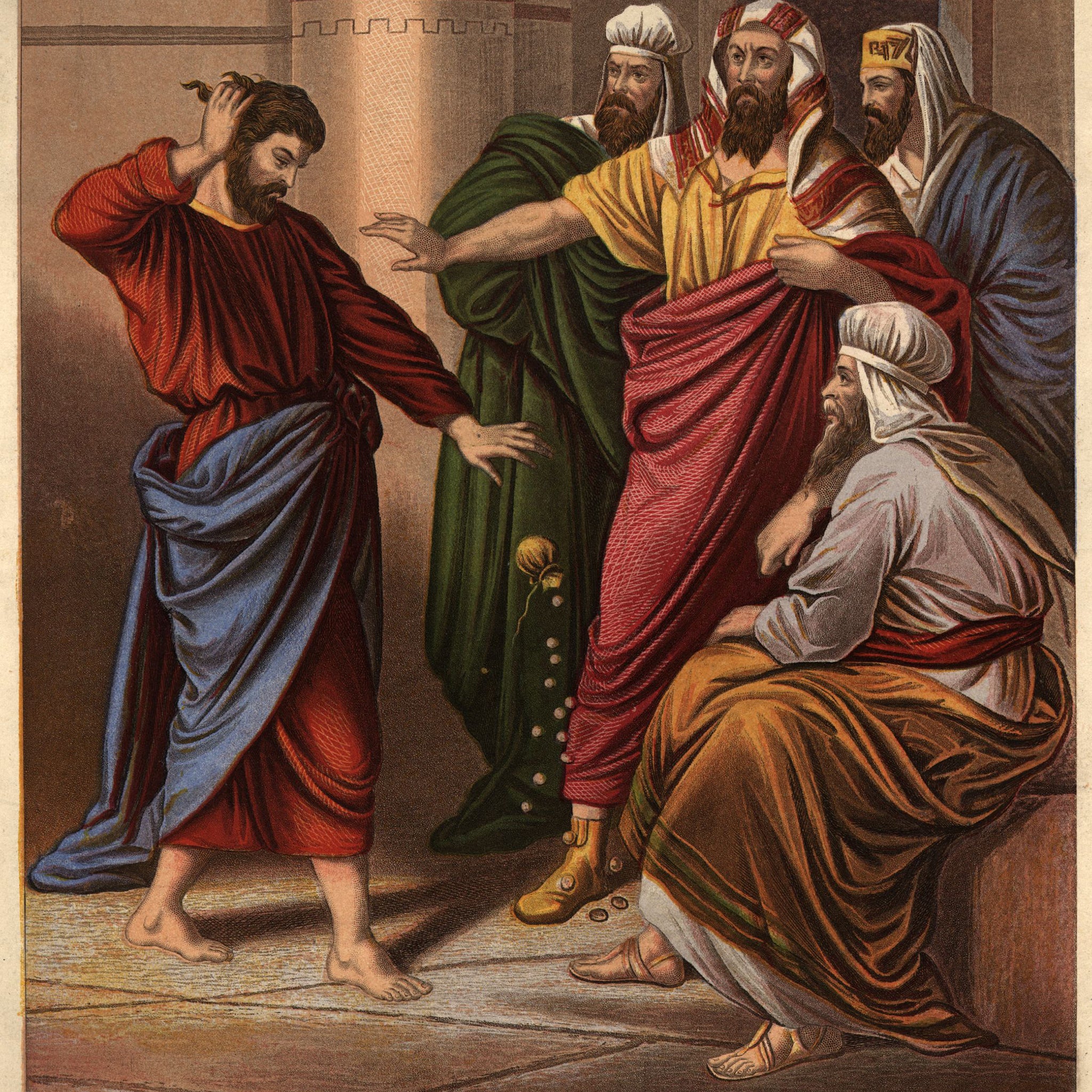

Easter’s almost here, the time when Christian communities reflect on the death of Jesus and celebrate his resurrection. It’s also a time when the biblical character Judas Iscariot is remembered for his betrayal of Jesus. In many Orthodox and Catholic countries an effigy of Judas is burned as part of the Easter rituals, a custom continued in areas of Liverpool in the UK until as late as the mid-20th century.

Judas’s bad rap doesn’t only extend to religious ritual, however, call someone a Judas and you’ll soon see how much significance the name retains in contemporary culture. In football, for instance, the act of moving from one team to its arch rival is known as a “Judas transfer”. Following footballer Sol Campbell’s controversial transfer from Tottenham Hotspur to Arsenal in the English Premier League, the central defender was known as “Judas” by Spurs fans, an accusation he still feels the need to address 14 years later.

The sting, then, from being labelled a Judas can last for decades – just ask Bob Dylan, who was branded a “Judas” when he switched from acoustic to electric.

Of course, the insult isn’t only reserved for footballers, musicians and MPs. Judas also been appropriated as a tool to incite and perpetuate prejudice and discrimination, including anti-semitism. Notoriously, Judas was embraced in Nazi propaganda as a vehicle to communicate stereotypes about Jews, as Peter Stanford explains in his 2015 book Judas: The Troubling History of a Renegade Apostle.

Even redheads haven’t escaped the curse of Judas. Medieval artists painted flame-haired Judases, contributing to gingerism, so much so that red hair was known as “the Judas colour”, referenced by Shakespeare in As You Like It.

Time for a retrial?

But while the name “Judas” may be synonymous with the most heinous of traitors, the wind maybe about to change for this much-maligned biblical character. As part of their Easter religious programming, on Good Friday the BBC will air In the Footsteps of Judas, a documentary focusing on Iscariot.

Presented by Gogglebox vicar Reverend Kate Bottley, the programme promises to “reopen the case against the Bible’s most notorious villain”. The Catholic Herald has already taken exception to the documentary, stating that “a perfectly good word exists in the English language for Judas’ actions: evil”.

But the Bishop of Leeds, Reverend Nick Baines, proves far more sympathetic to our biblical villain: “I feel a bit sorry for Judas,” he says. “He has gone down in history as the ultimate traitor who sells his friend for a few quid. Whether he is a traitor or a scapegoat he has had a lousy press.”

The BBC documentary isn’t the first attempt to rehabilitate Judas. The tide’s been slowly turning for Iscariot since the 1960s with the English language publication of Nikos Kazantzaki’s controversial novel The Last Temptation of Christ and the subsequent filmic portrayals of Judas as less archetypal evil villain and more complex political figure and friend of Jesus.

The evidence

The discovery of the Gospel of Judas in the 1970s was a further move towards re-imagining the character. The gospel offers a much more sympathetic character, a favoured apostle to whom Jesus says: “You will be cursed by the other generations – and you will come to rule over them.”

Despite the centuries of denunciation, the biblical text itself is more ambiguous than we might expect, too. It isn’t clear if Judas is a thief who betrays Jesus or if he is a true disciple, who is a central agent in the fulfilment of God’s plan and does the dirty work that the other disciples won’t do.

The gospels can’t help us to reach a decision because, as with many biblical stories and characters, their evidence is conflicting and often contradictory. Matthew 26:47-56, for example, suggests that Judas is fulfilling a necessary duty. Jesus says to him: “Do what you came for, friend” (26:50).

Indeed, none of the apostles are presented in a heroic light in the text since they all desert Jesus (26:56). Indeed, most of the gospels suggest that Judas’s betrayal is essential to the fulfilment of God’s plan (John 13:18, John 17:12, Matthew 26:23–25, Luke 22:21–22, Matt 27:9–10, Acts 1:16, Acts 1:20). The Gospel of John also suggests that Jesus knows of Judas’s betrayal and allows it (John 6:64 and 13:27-28) but, far less sympathetically, that Judas also was a liar and a thief (12:1-6).

In Mark (14:10-11), meanwhile, it isn’t clear that money is a motivation for his betrayal of Jesus, while the gospels of Luke and John both agree that Judas betrays Jesus because Satan enters into him, suggesting perhaps that Judas may not have been acting of his own free will (Luke 22:3-6; John 13:27).

While Judas may never be fully rehabilitated from his reputation as treacherous villain, perhaps we could cut him a little slack – if the Bible isn’t clear on his character, then how can we?

Katie Edwards, Director, SIIBS , University of Sheffield

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks