French fancy: Anna Pavord discovers a 19th-century garden near the Dordogne where box rules supreme

My brother has a farm in the Causse de Gramat, the high, wild, rocky country just north of the glorious Cele valley, south of the less interesting Dordogne. He's spent his working life as a vet, a horse doctor, but has always had a good eye for making gardens. He has the necessary practical skills too, which is much rarer. He can repair and build dry stone walls. He knows how to shift vast rocks with the forklift on his Massey Ferguson tractor and how to use the scrub-basher to rid his pastures of the prickly, low-growing juniper that had grown there unchecked for decades, swamping everything under its dour, prickly advance.

His little fields now are like medieval tapestries, stitched all over with wild flowers. The soil is very thin, the ground exceptionally stony, and the underlying rock fast-draining limestone. Though it must have been hellish ground to earn a living from, it provides the most perfect conditions for wild flowers. Grass scarcely exists. Instead you look over sheets of papery flowered white cinquefoil, thyme, acid-yellow spurge, a beautiful deep-blue veronica, pompoms of sheep's-bit scabious and thousands of orchids, never in clumps, but scattered singly everywhere: lady orchids, burnt- tip orchids, early purple orchids and in the shade of scrub oaks, the extraordinary folded purple asparagus-like spikes of violet helleborines. They were all there, waiting underground for the day when they would be liberated from the crushing prison of the juniper.

It's a potent dream, the flowery mead. For us it's a kind of idealised world, the way we think it looked before we spoilt it all. It's a luxury of course. Managing the fields for the benefit of wild flowers would not have been an option for any French farmer of the past, trying to feed a family from the fruit of his labours. But wandering around those complex, interknit pastures, I realised yet again how impossible it is to do this sort of thing on the kind of ground that most gardeners have. Our land is almost always too rich. You can't impoverish soil in the course of one generation. Rather than trying to garden with wildflowers (which usually means fighting a constant war against nettle, dock and other bullies), perhaps we should be grateful for our good land, use it to grow good food and spend the money and energy that we pour into wildflower gardening in fighting for and protecting the real thing instead.

Being so high and stony, many of the little farms in the Causse de Gramat are like my brother's, full of flowers. The verges along the lanes are the same. We drove through webs of empty lanes, the grass either side studded with orchids. When we'd overdosed on flowers, we went over to Marqueyssac, 9km west of Sarlat, to visit a garden that's almost entirely without them.

Marqueyssac overlooks the Dordogne, one of a whole clutch of grand, battlemented houses here that glare at each other from their respective peaks. In terms of situation, it is by far the most extraordinary, because it sits on a long, thin promontory of land that drops steeply to cliffs on both sides. In the middle of the 19th century it was owned by Julien de Cervel, a man in love with Italy and here, perched above the Dordogne river, he planted a garden as close to his Italian dream as he could manage. The ground is poor and stony, the terrain bizarre in its dimensions, but the result, more than 150 years on, is spectacular.

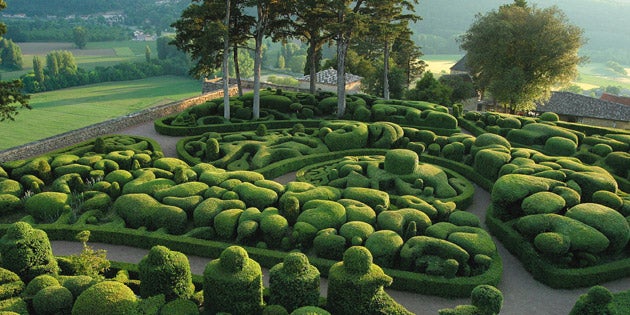

Marqueyssac is an almost entirely green garden, planted mainly with box under tall thin cypresses and umbrella pines. On the cooler northern slope of this strange peninsula are stands of lime and hornbeam. When de Cervel first planted his allées and parterres of box in 1861, they would have been laid out formally, geometrically. But then the garden was abandoned and by the time Kleber Rossillon took it on, 10 years ago, the box had had anarchic ideas of its own about what it wanted to do and how it wanted to grow.

In the parterres close to the house, rounded hummocks of the stuff look like dough rising: lopsided, smoothly interlocking organic shapes, bulging over the edges of the hedges that once contained them. Occasional mad box trees rise up from the molten mass, clipped like French poodles with bobbles on the end of each branch. Down below (the cliff drops 130 metres) is the glittering river and the rich, flat arable land that is the river's gift to those lucky enough to farm it.

The chateau at Marqueyssac, with its astonishing roof sweeping almost vertical (the stone tiles weigh more than 500 tons) sits at one end of the promontory. Three long paths, each different in character, lead to the belvedere 800 metres away at the other end. It's clever having three paths. If there were just two, you'd effectively do the same circuit each time. As it is, you are given constant choices, with sets of steps twitching through the undergrowth to connect one route with another.

Les Jardins Suspendus de Marqueyssac, 24220 Vezac, Dordogne are open daily (10am-7pm). During July and August there are special openings every Thursday until midnight when the garden is lit by candles. Admission 7.20€. For more information call 0033 5 53 31 36 36 or go to the website, marqueyssac.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks