Tolkien's black pine: Why do we love old trees?

Tolkien fans have been devastated by news that the author's beloved pine will be cut down. Emma Townshend looks at why the demise of old trees fills us with such great sadness

It was to be a relaxed family day out in Oxford Botanic Garden, a sunny afternoon of crafts and stories, and music from the local band Kismet. But as the musicians were setting up for a concert under the garden's biggest tree – a black pine, Pinus nigra, which dominates the centre of the four-acre, 17th-century walled garden – they could hear a series of strange creaks. "We were just about to hold one of our regular summer picnics," explains Dr Alison Foster, the garden's director, "and suddenly the musicians said they could hear little noises, like cracks." The disturbing sounds were coming from the tree.

"You could actually see a crack developing where the limb joined the trunk," says Dr Foster. "Someone even videoed it, bizarrely, and it's already on YouTube." The footage captures the moment, minutes later, that the massive limb crashes to the ground. The day's events last weekend continued under the shade of a nearby Japanese Katsura tree. But the fate of the ancient black pine was already in the balance.

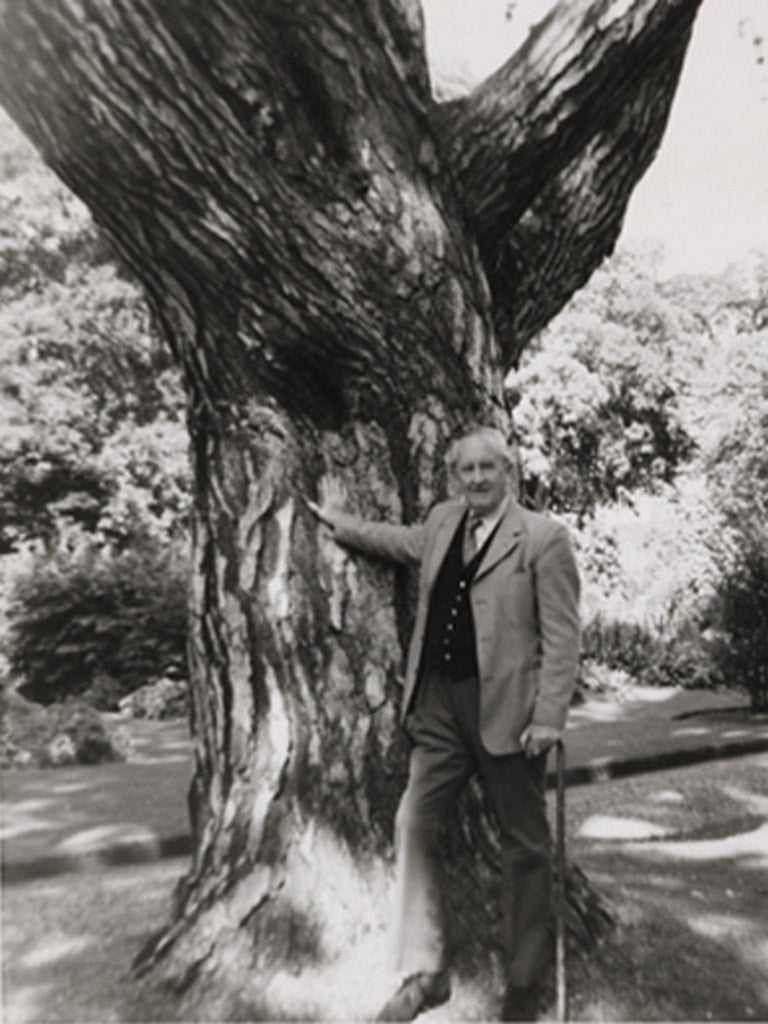

The tree, possibly as old as 215 years, has been totemic in Oxford for its associations to JRR Tolkien, who sat and wrote beneath its branches, creating his Ents (giant talking trees) in response to its whirl-patterned bark. "The last photo of Tolkien before he died," Foster says, "was him standing with his hand on the trunk of this tree." But after expert consultation, it was deemed unsalvageable, and the difficult decision was taken to remove it. As a result, emotions about the fatally damaged black pine have run high. "All of the staff are really sad, really upset," says Foster. "Even down to people who've only been here a couple of months. It's our most important tree. It's a living, breathing thing. And our regular visitors have been really supportive."

The garden has received letters and emails from across the world about "Tolkien's Tree", not all of them positive. "Lots of fanatics who believe they are living in the Shire think [we] are murdering the tree. And they are deadly serious. One particular person has managed to find everyone's work emails, has complained to the city council, and probably a number of other people, actually alleging that we are Saruman," says Dr Foster, in reference to Tolkien's fictional character and main protagonist in The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

The sight of big old trees mostly fills us with delight, and great sadness at their loss. A strange sense of melancholy was aroused at Kew earlier in the year as visitors watched the sawing up of an oak, planted in 1914 as an acorn collected from the battlefields of Verdun, and felled by this winter's high winds. Messageboards sprang into action, as regular visitors and friends of the garden expressed strong wishes that something "useful" be done with the wood.

Yet this doesn't stop trees from making us anxious. Bob Widd, an arboricultural consultant at BWA, who often acts as an expert witness in inquest and insurance cases, is precise about the dangers. "You can't rule out all danger from life," he says. "But the Victorians loved their trees. And now we've got the legacy of 100ft trees next to houses, and ever-increasing pressure on housing, so we're becoming more vulnerable to the big trees. We've got to manage them carefully to make sure humans are safe underneath them."

Dr Foster explains how garden managers must balance the concerns. "Everyone has a very different take – if you say, we're closing this area for health and safety, some people will be really cross, and say 'why can't I come in, it's entirely at my own risk?' And other people will say, 'why didn't you protect me?'"

Discussion among arborists and tree surgeons tends to focus on practical measures: trees from which one branch has already dropped should be felled, and benches and footpaths beneath such trees relocated. At the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the Arboretum team led by Tony Kirkham, star of TV's The Trees That Made Britain, has laid bark-chippings under some trees to discourage picnicking. "I would even avoid parking my car underneath a mature tree with horizontal branches," remarks Bob Widd.

The dangers of old trees, though, are still pretty small. About six people a year are killed by falling branches, mostly during storms. My slightly paranoid advice, though, after talking to the experts? Picnic under something small, like a magnolia or a mulberry, and leave the really big trees for admiration only.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks