Fierce competition in stellar nurseries doesn’t hinder star birth, astronomers say.

When condensing out of dense enough clouds, even the violence of star birth cannot keep gravity from birthing additional stars

Astronomers have assumed there is a feedback loop that limits the rate new stars are born in the universe. While gravity causes vast swaths of interstellar gas clouds to condense and form stars, the intense radiation from the newly born stars blows gas away, making it harder for other stars to form.

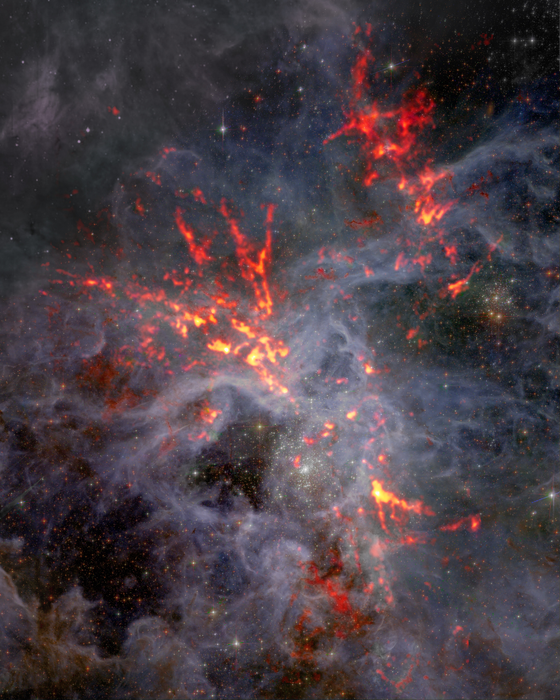

At least, that’s what astronomers thought until they took a careful look at one of the most active star-forming regions, the heart of the Tarantula Nebula in the large Magellanic cloud, some 170,000 light-years away.

A region within the nebula known as 30 Doradus is home to more than 800,000 newly formed stars, and new radio telescope observations presented Wednesday at the 240th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, show that in 30 Doradus at least, gravity always wins.

“We were expecting to find that parts of the cloud closest to the young massive stars would show the clearest signs of gravity being overwhelmed by feedback,” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign professor of astronomy and lead author of the study Tony Wong said in a statement.

“We found instead that gravity is still important in these feedback-exposed regions — at least for parts of the cloud that are sufficiently dense.”

Dr Wong and his colleagues used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, a radio telescope array in Chile to study 30 Doradus in unprecedented detail. Studying the gas clouds in the radio portion of the electromagnetic spectrum allowed them to trace its shape relative to the newly formed stars, which led to surprising results concerning the clouds’ structure.

“We used to think of interstellar gas clouds as puffy or roundish structures, but it’s increasingly clear that they are string-like or filamentary,” Dr Wong said in a statement. “When we divided the cloud into clumps to measure differences in density we observed that the densest clumps are not randomly placed but are highly organized onto these filaments. The filaments themselves appear to be shaped by gravity, so are probably an important step in the process of star formation.”

Studying 30 Doradus presents scientists with a unique opportunity according to Dr Wong. It’s close enough for astronomers to view in detail, but behaves similarly to some of the most distant galaxies, giving researchers insights into how the Cosmos has evolved over time.

“Thanks to 30 Doradus, we can study how stars used to form 10 billion years ago when most stars were born,” Dr Wong said in a statement. “One of the biggest mysteries of astronomy is why we are able to witness stars forming today. Why didn’t all of the available gas collapse in a huge fireworks show long ago? What we’re learning now can help us to shine a light on what is happening deep within molecular clouds so that we can better understand how galaxies sustain star formation over time."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks