Stargazing in November: Secrets of the charioteer

Auriga is often gets overshadowed by other winter constellations such as the mighty hunter Orion or the Zodiac star-patterns of Taurus and Gemini, Nigel Henbest writes. But it is worth paying attention to

Auriga (the charioteer) doesn’t get the same press as other winter constellations such as the mighty hunter Orion or the Zodiac star-patterns of Taurus and Gemini. But its leading light, Capella, is brighter than any star in these more lauded constellations, and it contains an object – Almaaz – that’s been dubbed "astronomy’s longest-running mystery".

In ancient Mesopotamia, this curved line of stars was seen as a scimitar, with glorious Capella as its handle. It then became a shepherd’s crook; and finally metamorphosed into a tribe of goats. The name Capella means "little nanny goat," and the triangle of faint stars to nearby represent her kids.

The Greeks renamed this star-pattern to celebrate the pioneering charioteer Erichthonius. Born lame, he invented the four-horse chariot to improve his mobility, and then realised it was also a formidable weapon of war. Traditional depictions of Auriga combine the two traditions, showing a charioteer incongruously carrying a goat and her offspring on his shoulder.

Capella is the sixth most prominent star in the sky, and the fourth brightest as seen from the UK. Despite appearances, it’s not a single star but consists of two stars, each 75 times brighter than the Sun, orbiting more closely than the Earth circles the Sun.

The second brightest star, Menkalinan, is moving towards the Sun and in a million years will pass so close that it will be the most brilliant star in our sky. Like Capella, it consists of two almost equally bright stars, but in this case the orbit is tipped up so that each star alternately passes in front of the other, partially eclipsing it and causing the overall light from Menkalinan to dim every two days.

One of the kid-stars, Saclateni, is also an eclipsing binary, but its stars follow a much more sedate orbit, with its light dimming every 2 years 8 months as a blue star is hidden by a giant orange companion.

Next to it, the star Almaaz has even odder eclipses. Every 27 years, it’s dimmed by something huge that partially hides Almaaz’s light for a whole two years. That’s far too long for the occulting object to be a star; and away from the eclipses astronomers cannot see any sign of this big, dark and partially transparent object.

Astronomers first discovered that Almaaz is variable back in 1821, but to this day no-one fully understands what is causing the eclipses. The best bet is that it’s a disc of murky dust that’s swirling around a companion star to Almaaz itself. The opaque disc hides the light from its central star; and it also eclipses Almaaz every 27 years as the two stars orbit each other. Let’s hope the next eclipse sheds more light on this weird object – just hang on until 2036!

In the meantime, scan Auriga with binoculars to track down three pretty star clusters, catalogued as M36, M37 and M38. And, under very dark skies, a telescope will show you the Flaming Star Nebula, a patch of interstellar gas and dust that’s lit up by a brilliant young star – AE Auriga – that’s been ejected from the star-forming region of Orion.

What’s Up

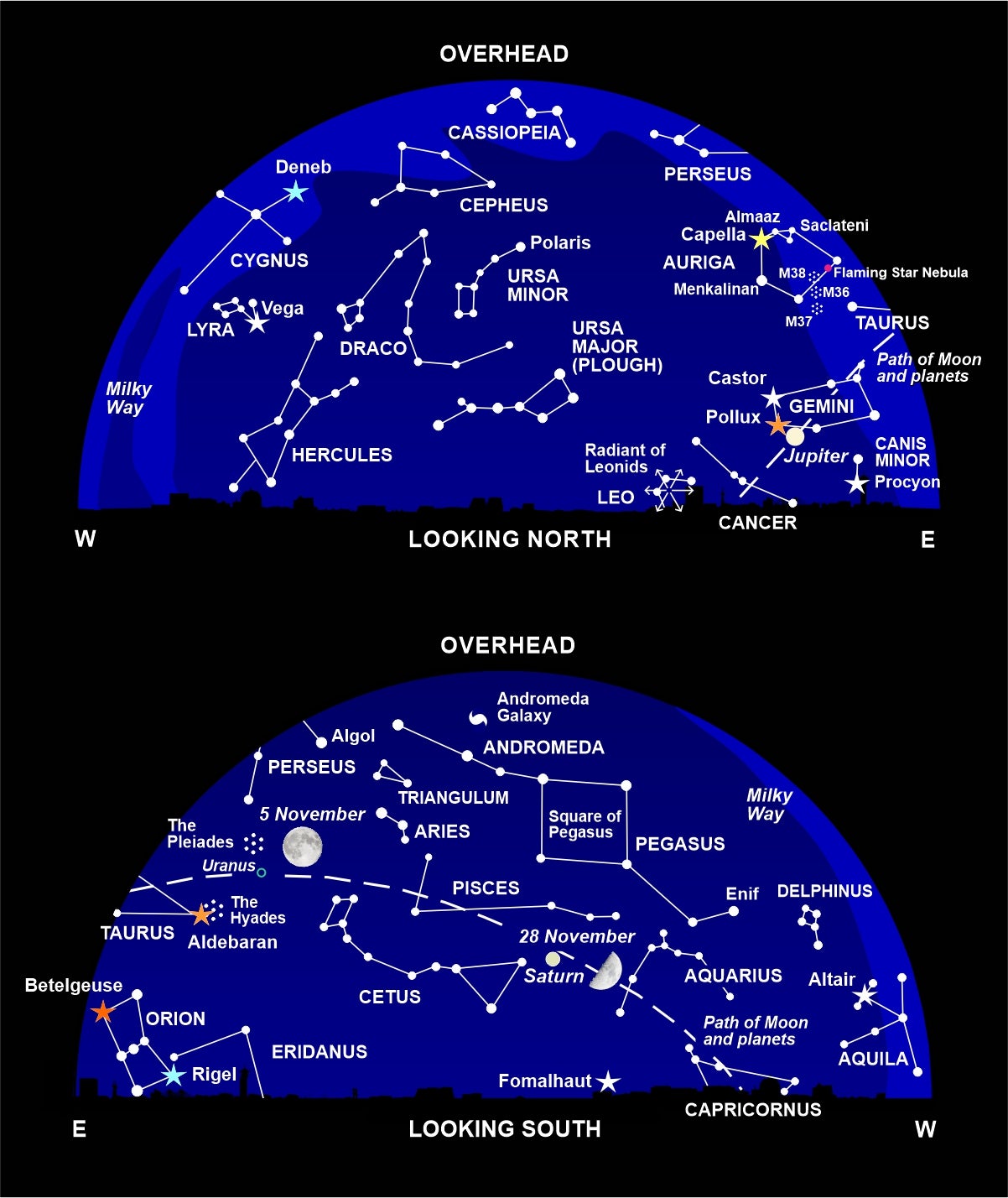

The two giants of the Solar System are gracing our evening skies this month. As it grows dark, you’ll find Saturn as the sole bright "star" in the southern sky: the Moon passes nearby on 29 November.

Over in the north-east, mighty Jupiter is rising about 8pm, more brilliant than any of the stars, with Castor and Pollux, the leading lights of Gemini (the twins) nearby. You’ll find the Moon above Jupiter on 9 November, with Castor and Pollux to its left.

To the right of Jupiter, you can make out the familiar humanoid shape of Orion (the hunter), fighting the celestial bull (Taurus) – featuring bright orange Aldebaran and the glittering Pleiades star cluster – with the prominent star Capella almost overhead.

Expect to spot some shooting stars on 17 November, as fragments of Comet Tempel-Tuttle smash into the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up as meteors that seem to streak outwards from the constellation of Leo (the lion). Occasionally, the Leonid meteor shower has been a veritable cosmic storm, the sky saturated with falling stars as our planet intercepts a particularly dense stream of cosmic debris – but we expect the show this year to be fairly desultory, with only a few meteors per hour at best.

On 21 November, Uranus is at its closest to the Earth this year, some 2769 million kilometres away. Lying to the lower right of the Pleiades, the seventh planet is just visible to the naked eye, but you’ll need really clear skies and no light pollution to spot the seventh planet. It’s an easy target in binoculars, though. Watch this region of sky intently from night to night, and Uranus is the faint "star" that is gradually moving.

Early birds are treated to brilliant Venus rising just before the Sun; but make the most of it this month, as by the end of November the Morning Star disappears into the twilight glow. On the last couple of mornings of the month, its place is taken by the innermost planet, Mercury, shining faintly low on the south-eastern horizon.

Diary

9 November: Moon near Jupiter

12 November, 5.28am: Last Quarter Moon

13 November, before dawn: Moon near Regulus

17 November: Maximum of Leonid meteor shower

18 November, before dawn: Moon near Venus

20 November, 6.47am: New Moon

21 November: Uranus at opposition

28 November, 6.59am: First Quarter Moon

29 November: Moon near Saturn

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks