Stargazing in January: Gas giants of the galaxy

Jupiter – the leading light of January’s sky – is big enough to contain 1,300 Earths, Nigel Henbest writes

_(jupiter-auroras2).jpeg)

Lording it over the heavens this month is the planet Jupiter, king of the gods in Roman mythology and the leading light of January’s sky. The planet is opposite to the Sun on 10 January, when it is highest in the sky at midnight and visible all night long.

Because the planets’ orbits are not perfect circles, Jupiter is actually closest to us – and at its brightest – the previous night, when it’s three times more brilliant than the first-ranked star, Sirius. Despite its immense distance of 633 million kilometres, Jupiter is prominent because of its vast size: the planet is 11 times wider than the Earth, leading astronomers to categorising Jupiter as a "giant planet".

Jupiter is big enough to contain 1,300 Earths, but it only weighs as much as 318 Earths – so the planet must consist of material that’s much less dense than our rocky world. With evidence from the robotic spacecraft that have visited Jupiter, astronomers know that it’s a huge gaseous ball with no solid surface, consisting mainly of hydrogen and helium, making Jupiter technically a "gas giant".

In the Solar System, there’s only one other gas giant: Saturn, currently visible to the west in the early evening. Leaving aside its glorious rings, Saturn has another claim to fame: this gas giant has such a low density that it would float in water – if you could find an ocean big enough!

Researchers have now detected a multitude of similar planets orbiting other stars: of the 7915 exoplanets known on 21 December 2025, around 30 per cent are gas giants. The planet HIP 11915 b, in the constellation Cetus, is an almost exact twin of Jupiter, orbiting a sunlike star at the same distance that Jupiter circles the Sun. But HIP 11915 b is very much the exception. Gas giants come in a huge range of sizes, masses and temperatures.

The first exoplanet to be discovered, in 1995, was a gas giant around half of Jupiter’s mass orbiting the star 51 Pegasi – and it now bears the name Dimidium, meaning ‘half’. But it doesn’t orbit at a sedate distance from its star. While Jupiter takes 12 years to circle the Sun, Dimidium orbits 51 Pegasi in only four days, following a much tighter orbit than Mercury’s path around the Sun. Its proximity to the star’s heat means that Dimidium roasts at 1,000°C, similar to the temperature of lava erupting from a volcano.

At the opposite extreme, the gas giant GU Piscium b is 70 times further from its star than the distance between the Sun and Neptune, and it takes 160,000 years to complete one orbit. Even odder is WISE 0855−0714, an object that’s between three and 10 times heavier than Jupiter and floats freely in the space between the stars. It’s probably a gas giant that’s been ejected from its original planetary system to live an independent life as a "rogue planet".

Astronomers are pretty sure that both hot jupiters and rogue planets were born in a swirling disc of gas and dust at roughly Jupiter’s distance from their own sun, and then migrated either inwards or outwards. But there are two competing theories as to how they formed.

More popular is the theory that solid particles in the disc clumped together to make a planet rather similar to our rocky Earth. This protoplanet lived in such a dense part of the disc that it was able to scoop up a huge amount of the surrounding gas, to grow into a gas giant.

But cracks have begun to appear in this theory. The Juno spacecraft orbiting Jupiter has found the planet doesn’t consist of a solid core separate from the surrounding gaseous layers: instead, the centre of the planet is a fuzzy mixture of rocks and gas. And calculations show the accretion of rocky material into a protoplanet would have been so slow that the surrounding gaseous disc could well have dissipated by the time the core got massive enough to grab it.

According to the alternative theory, the original disc became unstable as it swirled around the young star, forming a spiral shape – like cream stirred into coffee – which then broke up into clumps, and these each quickly collapsed under their own gravity to form a planet. Because the disc was made mainly of hydrogen and helium, the world that formed would naturally have been a gas giant.

The Atacama Large Millimetre Array radio telescope in the mountains of Chile is now probing details in the discs around many nearby young stars, and astronomers hope that these observations will soon reveal exactly how the gas giants in our galaxy were created.

What’s Up

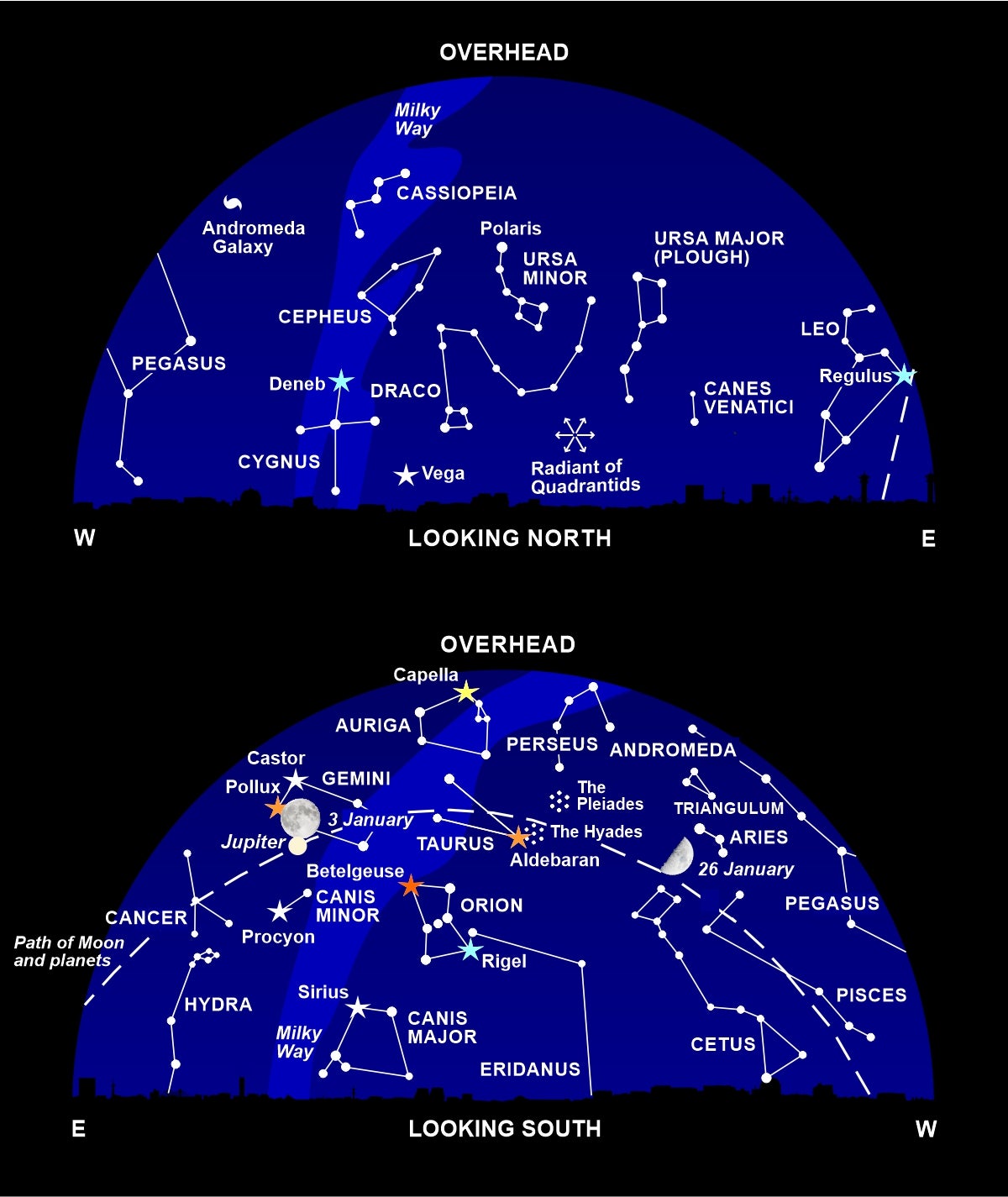

Jupiter dominates the night sky this month (see main story), shining near the twin stars of Gemini, Castor and Pollux. Mythology relates a close link between these three celestial bodies. Castor and Pollux were born together (along with their sisters Clytemnestra and Helen of Troy): Pollux was immortal, but Castor was doomed to die – and met his fate during a cattle raid. Pollux couldn’t bear to be separated from his brother, and so Jupiter raised them both to the heavens as celestial double act.

An unusually big and bright Full Moon lies near Jupiter on 3 January, the first of three supermoons this year – you’ll have to wait until December to see the best supermoon of 2026. On that same day, the Earth is nearest to the Sun – a "mere" 147 million kilometres away – and there’s an annual shower of shooting stars, the Quadrantids, though the light from the supermoon will wash out all but the most brilliant meteors.

On 9 January, Jupiter is nearest to the Earth and at its brightest this year. The following day it’s opposite to the Sun in the sky. The Solar System’s second-biggest planet, Saturn, is over in the west during the evening. You’ll find the crescent Moon near Saturn on 22 and 23 January.

A few nights later, on 27 January, the Moon moves in front of the Pleiades star cluster and hides some of its stars. Binoculars will help you see the stars so close to the overwhelming light from the Moon.

Away from all this action, the starry skies are magnificent this month. The familiar humanoid shape of the hunter Orion lies to the lower right of Jupiter, featuring bright red Betelgeuse and blue-white Rigel. Below lies Sirius, the brightest star in the sky; while to the upper right you’ll find Aldebaran in Taurus, with Auriga’s leading light Capella almost directly overhead.

Diary

3 January, 10.03am: Full Moon near Jupiter; supermoon; Earth at perihelion; maximum of Quadrantid meteor shower

6 January: Moon near Regulus

9 January: Jupiter closest to Earth

10 January, 3.48pm: Last Quarter Moon; Jupiter at opposition

18 January, 7.52pm: New Moon

22 January: Moon near Saturn

23 January: Moon near Saturn

26 January, 4.47pm: First Quarter Moon

27 January, 8pm to 11.30pm: Moon occults the Pleiades

30 January: Moon near Jupiter

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks