Stargazing in August: Heartbeats of the universe

What they lack in visual splendour, a number of fainter stars more than make up for in cosmic importance, Nigel Henbest writes

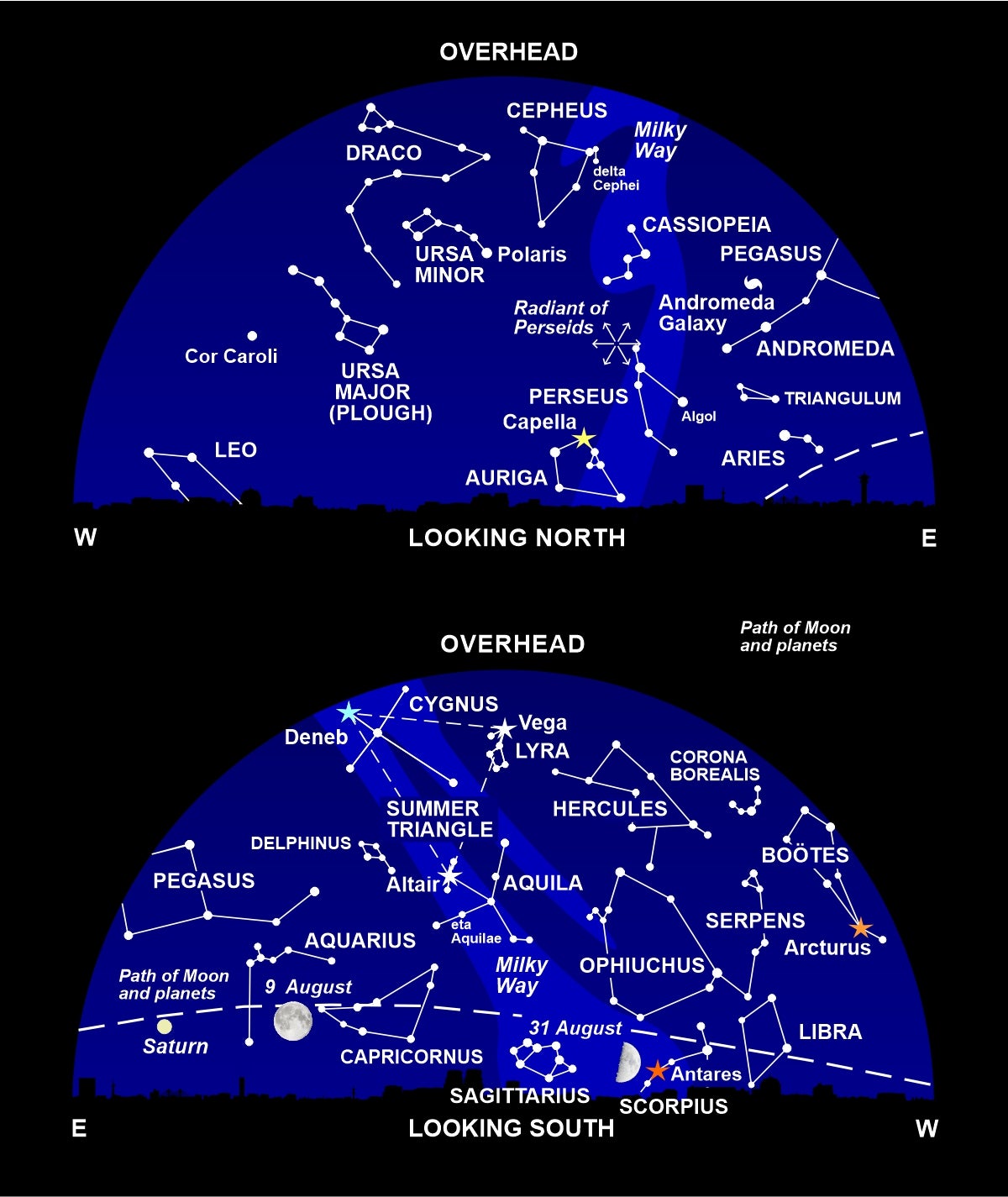

Away from the razzle-dazzle of bright summer stars like Vega, Arcturus and Antares, take some time to seek out two fainter stars this month. What they lack in visual splendour, they more than make up for in cosmic importance: delta Cephei and eta Aquilae have pointed astronomers the way to measuring the size of the Universe.

In the late eighteenth century, the British astronomer Edward Pigott was intrigued that sky catalogues sometimes listed the same star as being quite different in brightness. He suspected that these weren’t errors by previous astronomers, but meant that some stars actually change in brilliance. Pigott made it his mission to check out the prime suspects, and he teamed up with a neighbour in York, John Goodricke, who was still in his teens, and deaf from an early age.

First, they found that Algol, in the constellation Perseus, regularly dimmed in brightness. Goodricke correctly proposed that a darker object was orbiting the bright star and obscuring its light.

Then, in 1784, Pigott found that a faint star in Aquila (the Eagle) was pulsating in brightness every seven days. Known only by its catalogue designation, eta Aquilae lies below brilliant Altair (see starchart), and over a period of a week it doubles in brightness and then fades again.

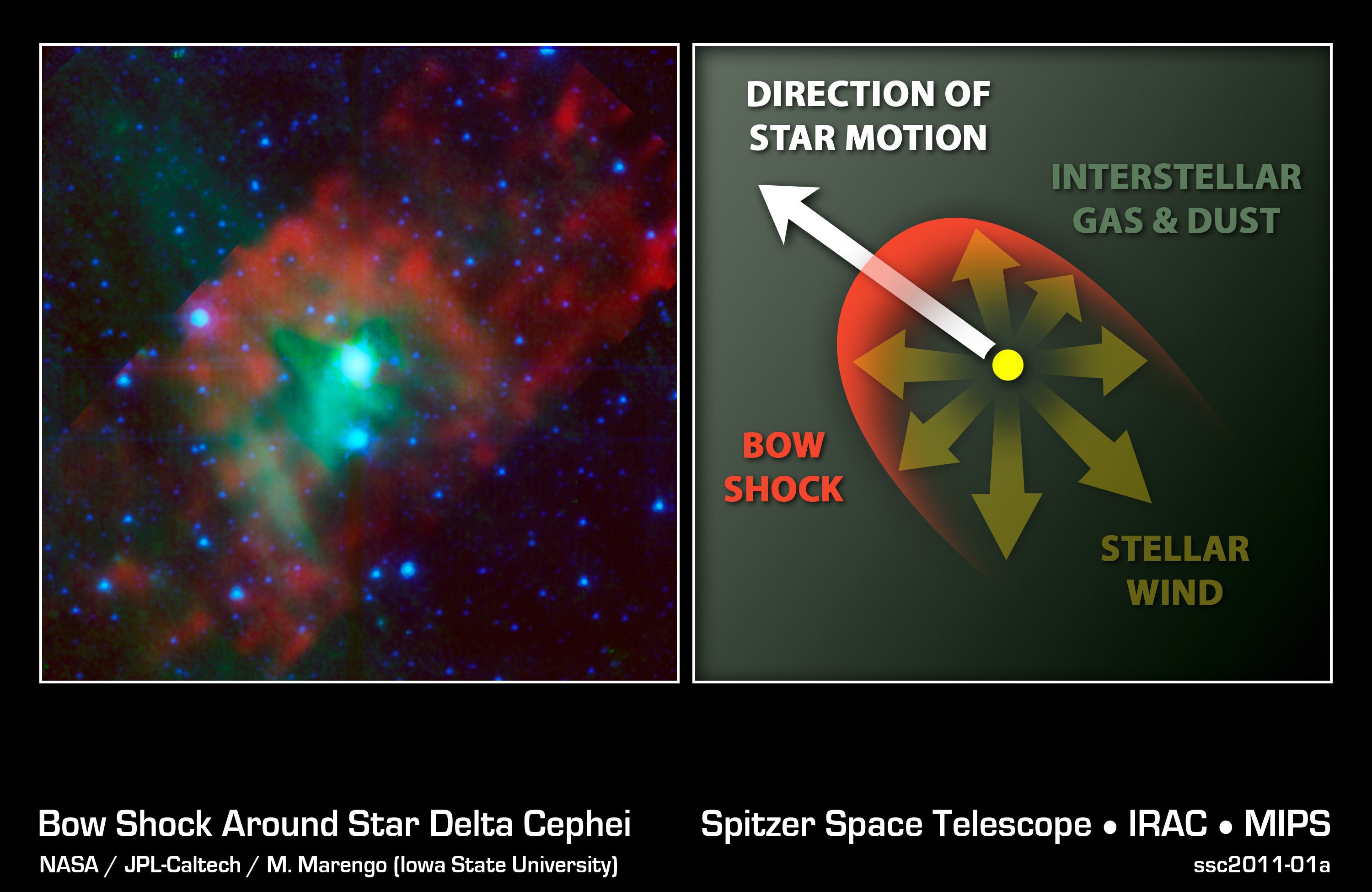

A month later, Goodricke discovered a remarkably star in the constellation representing King Cepheus. Delta Cephei (see starchart) rises quickly to maximum brightness and then fades more slowly, over a period of about 5 days. The chill nights Goodricke spent observing this star in the northern English winter led to him contracting pneumonia, and he died at the age of 21. But ‘his’ star went on to name a whole class of variable stars, including eta Aquilae, which we now call Cepheids.

Like our local star, a Cepheid is made primarily of hydrogen and helium. Hot helium is very effective at absorbing the intense light streaming out from the star’s core, and this trapped radiation pushes outwards, making the star grow larger. As it expands, the outer regions of the star cool down.

When it’s cooler, helium become much less effective in trapping light, and so the star’s energy flows out to space unimpeded. With less radiation pressure pushing outwards, gravity takes control and makes the star shrink again.

As it contracts, the gas heats up and the helium becomes more efficient in intercepting the energy from the star’s core. The trapped radiation pushes outwards to start another cycle of expansion, to be followed by contraction – a regular heartbeat on the cosmic scale.

In 1908, the American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt was checking out variable stars in a neighbouring galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud, when she made an unexpected discovery. The Cepheid variables with the longest periods were also the brightest.

The implications were immense. Cepheids are so brilliant that astronomers can spot them in very remote galaxies, and can distinguish them from other variable stars by their distinctive heartbeat. Once an astronomer has measured a Cepheid’s period of light variation, then Leavitt’s discovery reveals how bright the star actually is. The star’s light is dimmed by its immense distance, and by comparing the actually luminosity of the Cepheid with how faint it appears in the sky, astronomers can work out how far way the star lies – and hence the distance of its home galaxy.

The record-holder is the galaxy NGC 5468, where the Hubble Space Telescope and its bigger sibling, the James Webb Space Telescope, have observed Cepheid variables even at a distance of 130 million light years. With the locations of galaxies like this firmly pinned down by their Cepheids, astronomers can use them as a first stepping stone to working out the distances to more remote objects throughout the visible universe.

What’s Up

Most of the excitement this month is happening in the morning sky; but before unveiling these highlights, here’s a quick round-up of what’s on view before midnight.

Sun, and it won’t be visible again until next year.

Hugging the southern horizon is another ruddy object, the red giant star Antares – whose name, aptly, means "rival of Mars" You’ll find the Moon next to Antares on 31 August.

Higher in the sky are three stars that form the Summer Triangle: Vega, Deneb and Altair. And over in the east, Saturn is rising about 9.30pm. The Moon lies near the ringworld on 11 and 12 August.

The night of 12 August is also the time when the annual Perseid shower of meteors reaches its peak. But don’t expect too much this year, as there’s a bright Moon around and its light will drown out all but the brightest shooting stars. If you catch a meteor and make a wish, spare a thought for American astronomers Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, who discovered the Perseids’ parent body – Comet Swift-Tuttle – in 1862.

In the morning sky, we have the glorious sight of the two brightest planets rising together, in the east, around 3.30am. At the start of August, brilliant Venus is higher than the giant planet Jupiter – a bit dimmer than Venus, but still outshining all the stars in the sky. But they are moving together, and on the morning of 12 August they are so close that you can see them together in binoculars or a small telescope.

Venus, though brighter, appears as a rather smaller globe. In the case of Jupiter, look out for the dark bands on its flattened disc, and its four brightest moons lined up on either side of the giant planet itself.

As the days go by, Jupiter rises higher while Venus sinks towards the horizon. And, in the second half of the month, they’re joined by fainter Mercury, down to the lower left of Venus. There’s a lovely view on the morning of 20 August, when the crescent Moon lies between Jupiter and Venus. And before dawn on 21 August, the Moon lies just above Mercury, with Venus and Jupiter to the upper right.

Diary

8 August, 8.55am: Full Moon

11 August: Moon near Saturn

12 August, before dawn: Venus very near Jupiter

12 August: Moon near Saturn; maximum of Perseid meteor shower

16 August, 6.12am: Last Quarter Moon

19 August: Mercury at greatest elongation west

20 August, before dawn: Moon between Venus and Jupiter

21 August, before dawn: Moon near Mercury, Venus and Jupiter

23 August, 7.06am: New Moon

31 August, 7.25am: First Quarter Moon near Antares

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks