A solar eruption will narrowly miss the Earth on Thursday

A massive eruption on the far side of the Sun may create arctic auroras Thursday, but not geomagnetic storm

Earth just dodged another high energy plasma bullet, as space weather watchers determined the radiation released by a solar eruption on Monday will mostly miss our planet.

Chances for minor impacts to Earth’s magnetic field, and some glowing arctic auroras, on Thursday, persist, however.

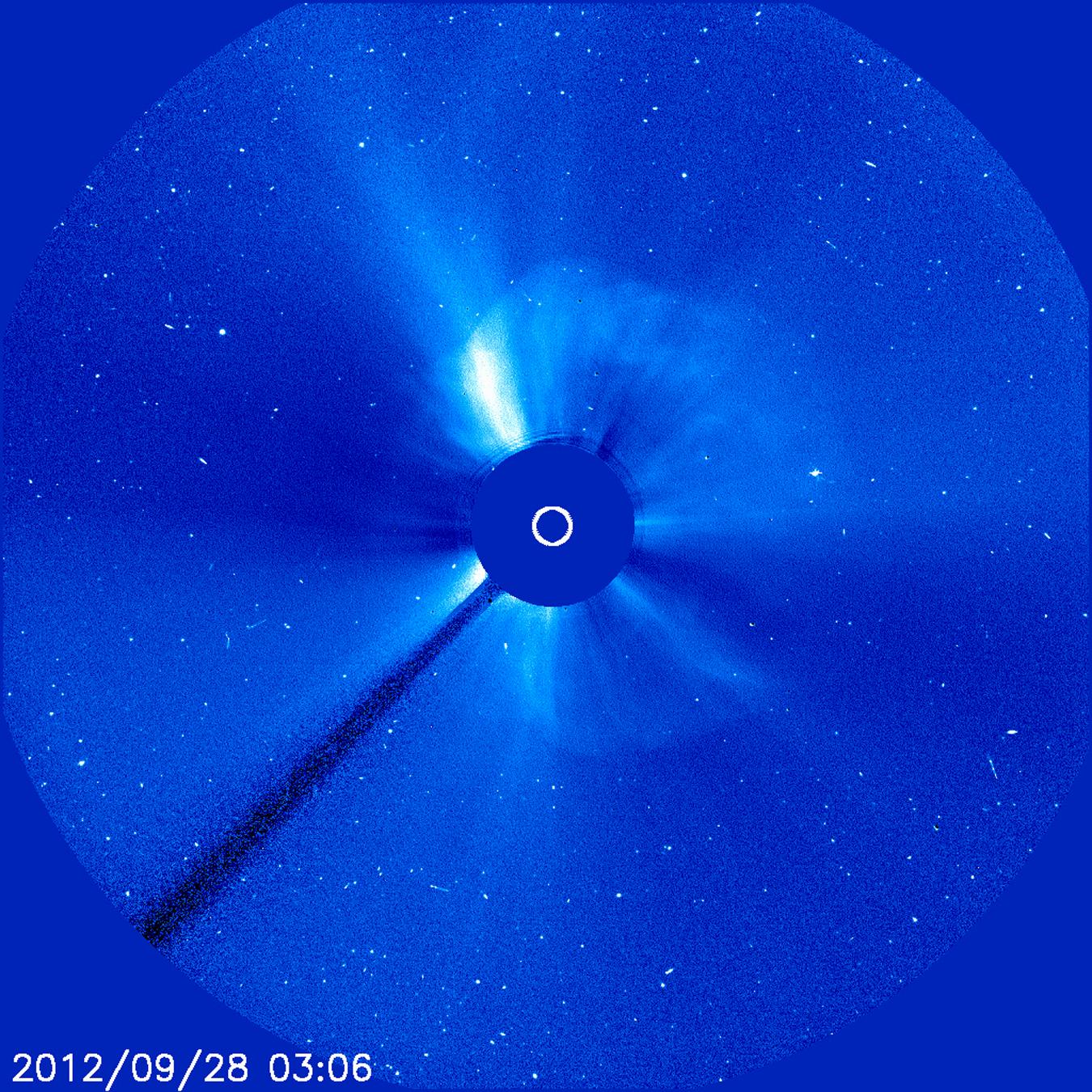

Nasa and the European Space Agency’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO spacecraft, observed a massive coronal mass ejection from the Sun on 21 March, according to reporting by spaceweather.com. A coronal mass ejection is a plume of charged particles and magnetic fields thrown loose of the Sun during a solar eruption.

When particles from a coronal mass ejection strike the Earth, they transmit a tremendous amount of energy into the planet’s magnetic field, generating a geomagnetic storm that, when powerful enough, can swell the atmosphere and drag down satellites. Such a geomagnetic storm brought down 40 SpaceX satellites in early February.

Another massive solar eruption on 15 February would have produced a similar geomagnetic storm had it not taken place on the far side of the Sun. Thursday’s predicted near-miss stems from the same situation — the solar eruption and coronal mass ejection of 21 March took place on the far side of the Sun, so that most of the charged particles will miss our planet.

Solar eruptions increase in frequency and intensity as the Sun becomes more magnetically active over the course of its 11-year sunspot cycle, these dark portions of the Sun’s surface are linked to powerful magnetic fields that twist and eventually snap to produce solar eruptions.

As the Sun is currently in the upward swing of the sunspot cycle, with activity peaking around 2025, solar eruptions, and potential geomagnetic storms, will be a hazard satellite operators and space agencies will have to deal with for much of the 2020s.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks