How a small team in Baltimore brought the Webb telescope’s images to life

A big showy rocket launch put the Webb Telescope in space, but a small group of people in Baltimore worked behind the scenes to make its first images possible, Jon Kelvey writes

From its orbit one million miles from Earth, the now operational James Webb Space Telescope has finally returned its first images, including a deep field view of thousands of galaxies, shining like gems billions of light years away. But as stunning as those images are, they’d be nothing but an array of black pixels without passing through the Steven Muller Building, a modest khaki-brick structure tucked into the trees on the Johns Hopkins campus in Baltimore, Maryland.

There are few permanent features alerting the casual passerby that the building is the headquarters of the Space Telescope Science Institute, (STScI), though a blue and gold banner hung over the main entrance proclaiming “Go, Webb, Go!” provides an obvious clue. STScI began operating the Hubble Space Telescope on behalf of Nasa and scientists in 1990, and the institution’s mission has now expanded to include Webb. STScI controllers helped guide the new space telescope through the deployment and commissioning process, and in early June, began taking the first images with the big gold telescope.

And those images don’t magically appear in brilliant colour and balanced brightness. The raw data captured by Webb must be processed, cleaned of artifacts, and colourised by specialists at STScI who work behind the scenes to process all Webb images released to the press over the years the telescope does science. And it’s in many ways an artistic process as much as a technical one.

Shedding light

On 24 June, roughly two weeks before the first Webb images would be released to the public, science visuals developers Joseph DePasquale and Alyssa Pagan sat in their shared office surrounded by large computer screens, demonstrating how they processed the very first Webb images beamed back to Earth. With the flick of a mouse, Mr DePasquale took the first Webb deep field image, an array of glowing gems, actually thousands of incredibly distant galaxies, and returned the image to the way it came to him: a black screen.

“The pixel values are mostly dark, because the sky is mostly dark, and only the brightest regions show through when you see it at first,” he said. Mr DePasquale and Ms Pagans’ task is to use a suite of software to raise the brightness of the image to allow people to see the darkest details, without washing out the bright regions. “All this information is hidden in here, because it’s really very dim.”

With a few more clicks at the keyboard, Mr DePasquale raises the brightness in a process known as “scaling” the data, revealing a grayscale version of the Webb deep field. Adding colour comes in a later step, but that must wait until Mr DePasquale deals with another problem introduced by scaling the image to make it bright enough to see.

“Bright stars in Webb will tend to saturate to the point where the detector no longer gives you valid information,” Mr DePasquale said. “When that runs through the pipeline, you end up getting a black hole in the centre of a bright star.”

This effect can be seen in the Webb image released on 6 July as a sneak peek, an orange-hued star-field captured by the space telescope’s guidance instrument. At the centres of bright, spiky stars are black circles looking like holes burned through a film negative.

“We were sweating this out as we were getting closer and closer to the [Webb image release] date,” Mr DePasquale said, but he eventually hit on a computer script that would fill in the black holes with the values of neighbouring pixels. It’s the sort of novel solution required with the Webb data, he adds, because unlike the familiar workflow for developing images from Hubble data, with Webb “the process is sort of in flux right now because everything is new.”

Which Webb first?

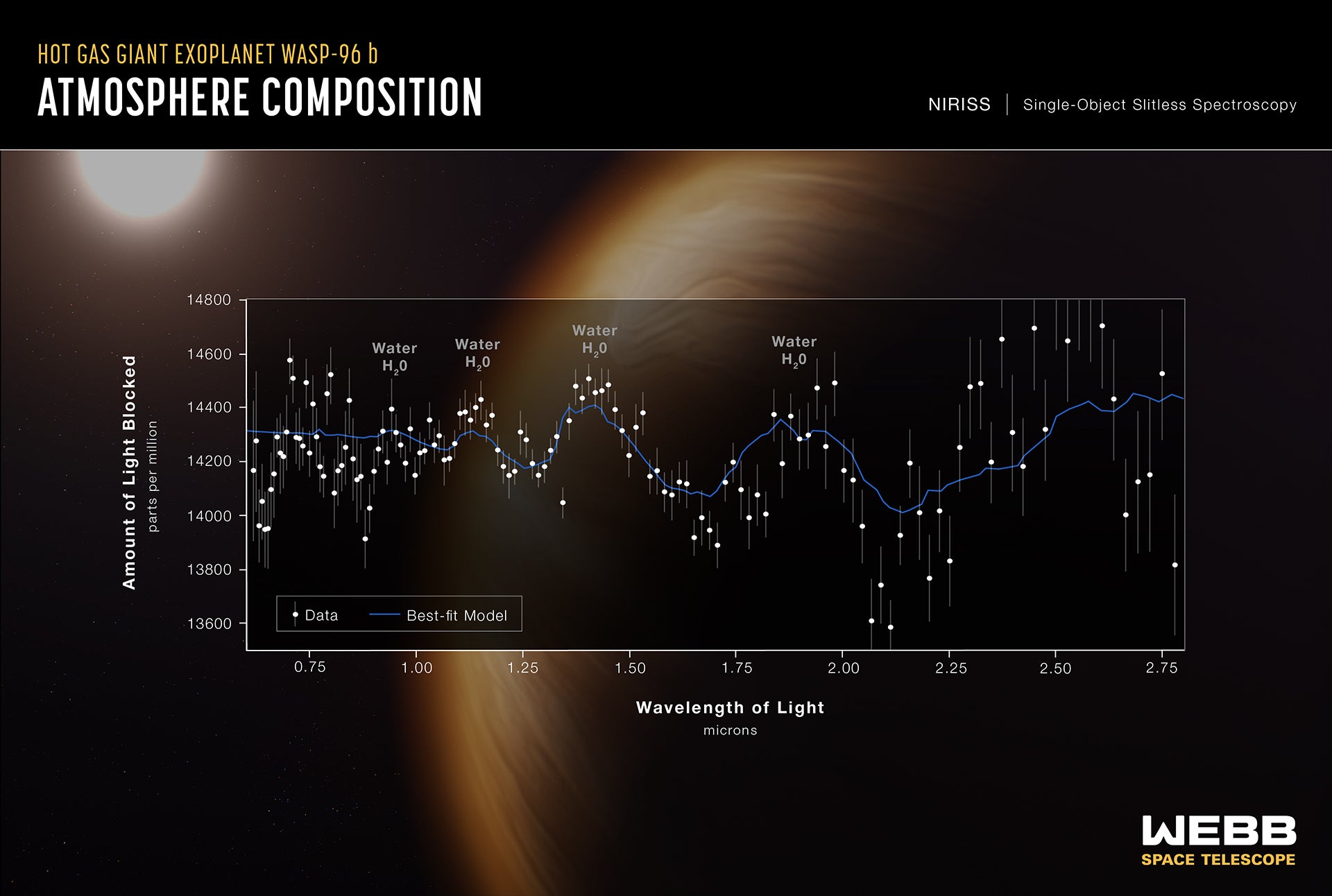

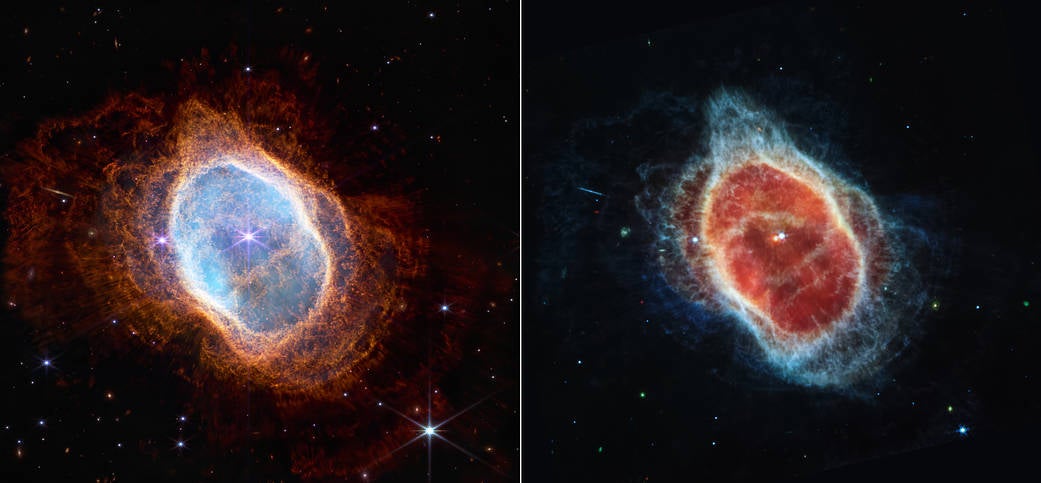

The Webb deep field image was the first of five images selected by STScI and Nasa to show the tangible results of the more than 20 years and $10 billion it took to design, develop, build, test, launch, deploy, configure and commission the most sophisticated telescope ever constructed. US President Joe Biden previewed the deep field image from the White House on 11 July, while the remaining four images were revealed the following morning through Nasa’s website. The full set of images includes the deep field, the spectrum, or pattern of light filtered through the atmosphere of the exoplanet Wasp 96 b, and images of the Carina nebula, the Southern Ring Nebula, and Stephan’s Quintet, a collection of five galaxies locked in a tight gravitational dance.

But as of 24 June, what images the public would see first, and exactly what they would look like, was still a matter of discussion.

“The charter we have is to demonstrate to the world that the observatory is ready to do science, to celebrate that it’s ready to do science,” said Klaus Pontoppidan, an associate astronomer at STScI. He was one of about a dozen people in a small conference room on 24 June to discuss the images to be released to the public.

“Almost nobody else in this building or even at NASA has seen this,” Dr Pontoppidan added. “It’s just this room.”

The small group had been meeting most mornings all month to discuss the latest images and processed by Mr DePasquale and Ms Pagan and displayed on a huge wall-hung monitor. On 24 June, the discussion turned to which version of the Carina nebula image would make the public release, an image taken with Webb’s near-infrared instrument, NIRcam, or its mid-infrared instrument, MIRI.

While the NIRCam image highlighted the orange and gold dust clouds, MIRI peered through the dust to reveal more stars, but with the gas clouds showing up in shades of greyish blue against a red “sky,” a controversial aesthetic.

“To me, the greyish blue, the way it turned out on the MIRI image, that is not attractive,” came one of many overlapping comments in the room.

But there was a third option presented by Mr DePasquale and Ms Pagan — a combination of NIRCam and MIRI imagery, a blend of perspectives preserving the contrast of the MIRI image while overlaying the many details and stunning colours of the NIRCam image.

“It’s like the best of both worlds,” Ms Pagan said.

The group ultimately settled on the Carina combination image, which is what the public saw on 12 July.

Colour coordination

But the creation of the Carina image highlights another way in which creating visible images from Webb’s data is a creative process in its own right, particularly when it comes to the colour process.

Step back to the fact that most raw Webb images are essentially blank to the human eye. The distant objects it images are in many cases incredibly faint, too faint to register in the colour perceiving cone cells in the human eye. That’s often true even with less exotic astronomical observations.

“Look through a telescope at a planet like Jupiter or Saturn, and it looks almost black and white, because the light is so dim that it’s really only activating the rods in your eyes and not the cones,” Mr DePasquale said. “You’re not really getting colour information.”

In Webb’s case, add to that the fact that the telescope sees only in infrared, wavelengths of light too long for human eyes to see at all, no matter how bright. To make Webb’s images visible then, Ms Pagan and Mr DePasquale must transpose frequencies of light invisible to human eyes into the visible portion of the spectrum.

“Telescopes are designed with filters to separate out the different colours, and then we assign those colours chromatically,” he said. “The shortest wavelengths of light are assigned to blue colours, then you move from blue to green to red as you increase wavelength.”

That’s a system that worked well with Hubble, that saw only into the near-infrared, and so far seems to work well for Webb’s NIRCam, according to Ms Pagan.

“But when we go into the mid-infrared with MIRI what we are getting is very different, which is a challenge,” she said. To avoid garish colour combinations like the MIRI image of Carina, they had to get a little creative with the colour mapping, “so it might be red, orange and cyan” rather than red, green and blue.

The process might be entirely different for scientists using Webb to study a particular aspect of a distant object, Ms Pagan noted. Rather than attempting to transpose non-visual wavelengths of light into the visible spectrum in a way that makes visual sense, a researcher might request colour highlighting based on some phenomenon of interest, such as organic gas clouds. Researchers may also call upon their office’s services when publicizing the results of their research with Webb.

“There’s a web page for scientists to submit their proposals for a press release,” Mr DePasquale said. “They can go through that avenue, contact the news office here, and then we’ll determine if it’s actually press worthy. If so, then it comes to us to process the data.”

The processing can be a lot of work, especially with Webb — developing the Carina Nebula image took 16 hours — and Ms Pagan and Mr DePasquale worked through weekends in the days leading up to the release of the first Webb images. But the work is also so captivating, they would have processed the new images even without the urgency of the imminent public release.

“The first data set came in on a Saturday morning, and I had to drive up to Philly for a family party,” Mr DePasquale said. “I’m at the party. And I’m like, ‘I just want to be working on that image.’”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks