The fights and crimes of Carlos Monzon, Argentina’s violent idol and one of boxing’s greatest middleweights

There was never going to be a fairy tale end to the life, fights and crimes of Argentina’s finest boxer

There was never going to be a fairy tale end to the life, fights and crimes of Argentina’s finest boxer Carlos Monzon.

In 1988 he fell from a second-floor balcony and injured his arm; he was drunk and holding tight his latest girlfriend Alicia Muniz as he plunged. She died, an accident he claimed. The coroner disagreed and the following year Monzon was sentenced to 11 years in prison for her death in a courtroom packed with a thousand people, most weeping, at the fate of their idol.

Muniz was the latest woman to make the headlines with Monzon. His first wife shot him in the back and his second wife was Argentina’s number one actress. He had the bullet in his back for the rest of his life, a reminder of the violent times he kept and the women he loved.

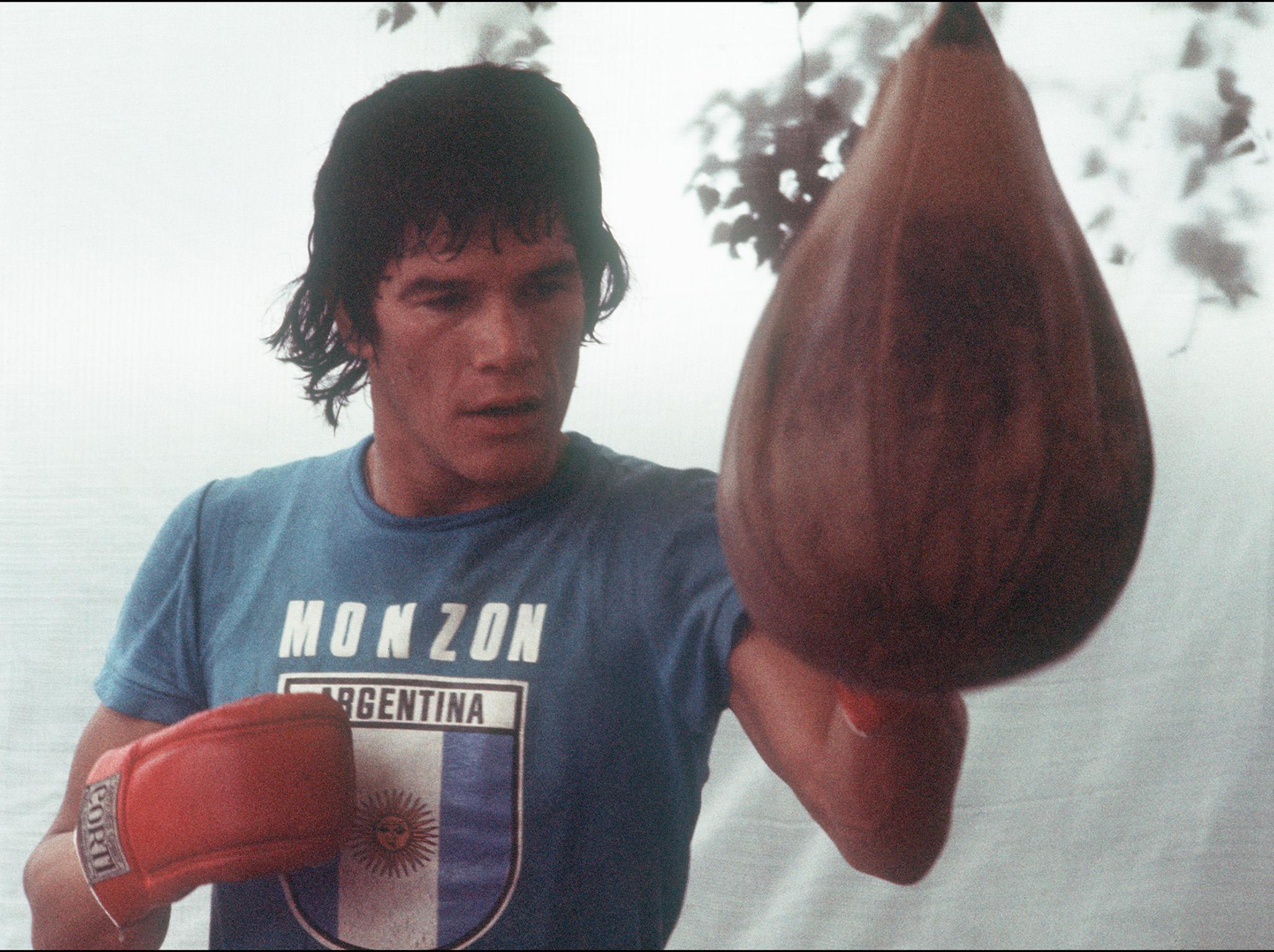

As a child he was sold for a few pesos for fights in streets, one of 12 he was silent, angry and poor. Monzon was a troubled boy of 20 when he turned professional for peanuts in 1963, a dark-haired, sullen scrapper on a circuit so crude that it is barely recognisable as a professional sport. He lost three times on points in a year and then fought 81 more times without loss before walking away in 1977. It is the type of statistic that will never be equalled in the squeaky clean modern business.

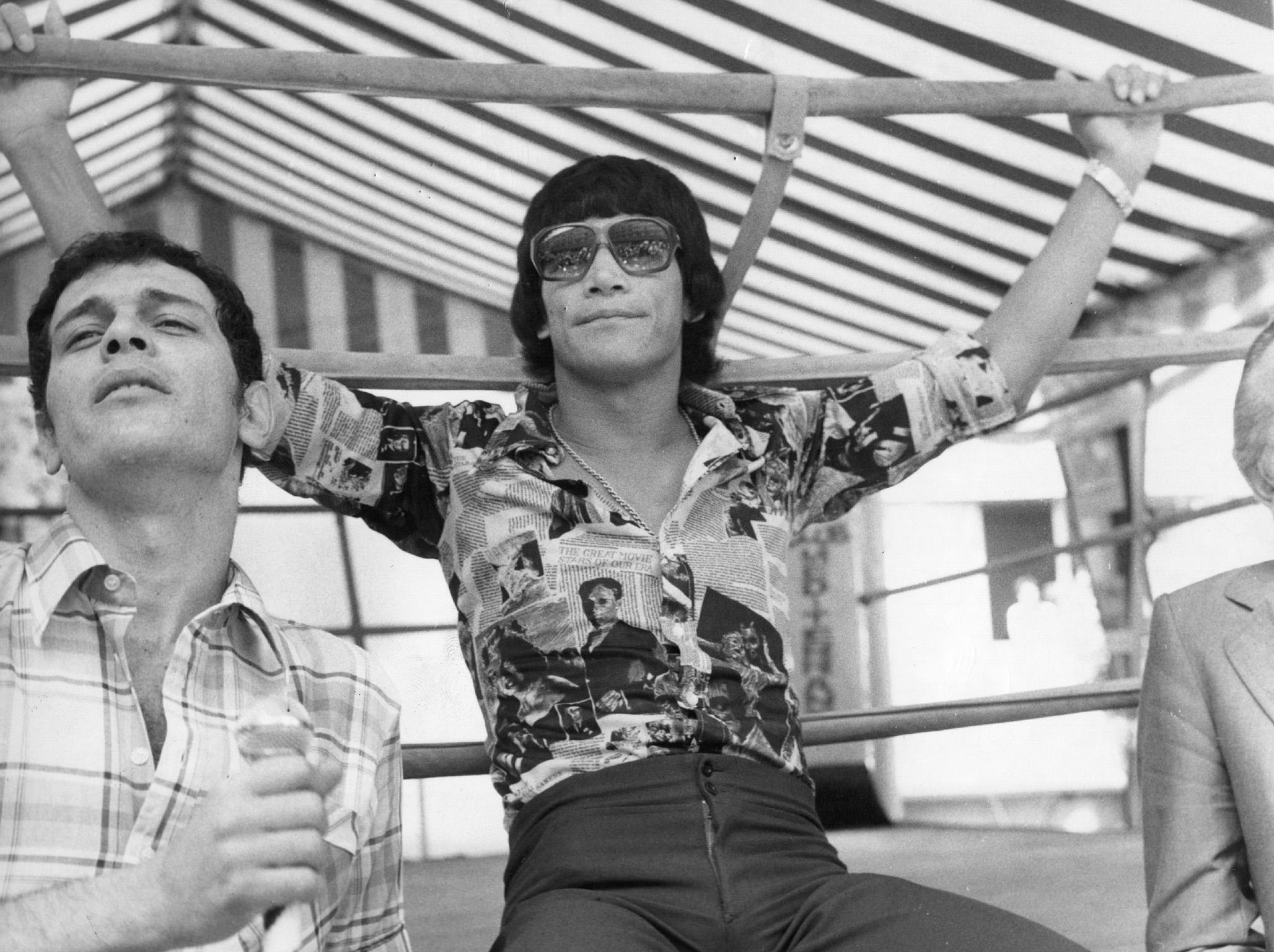

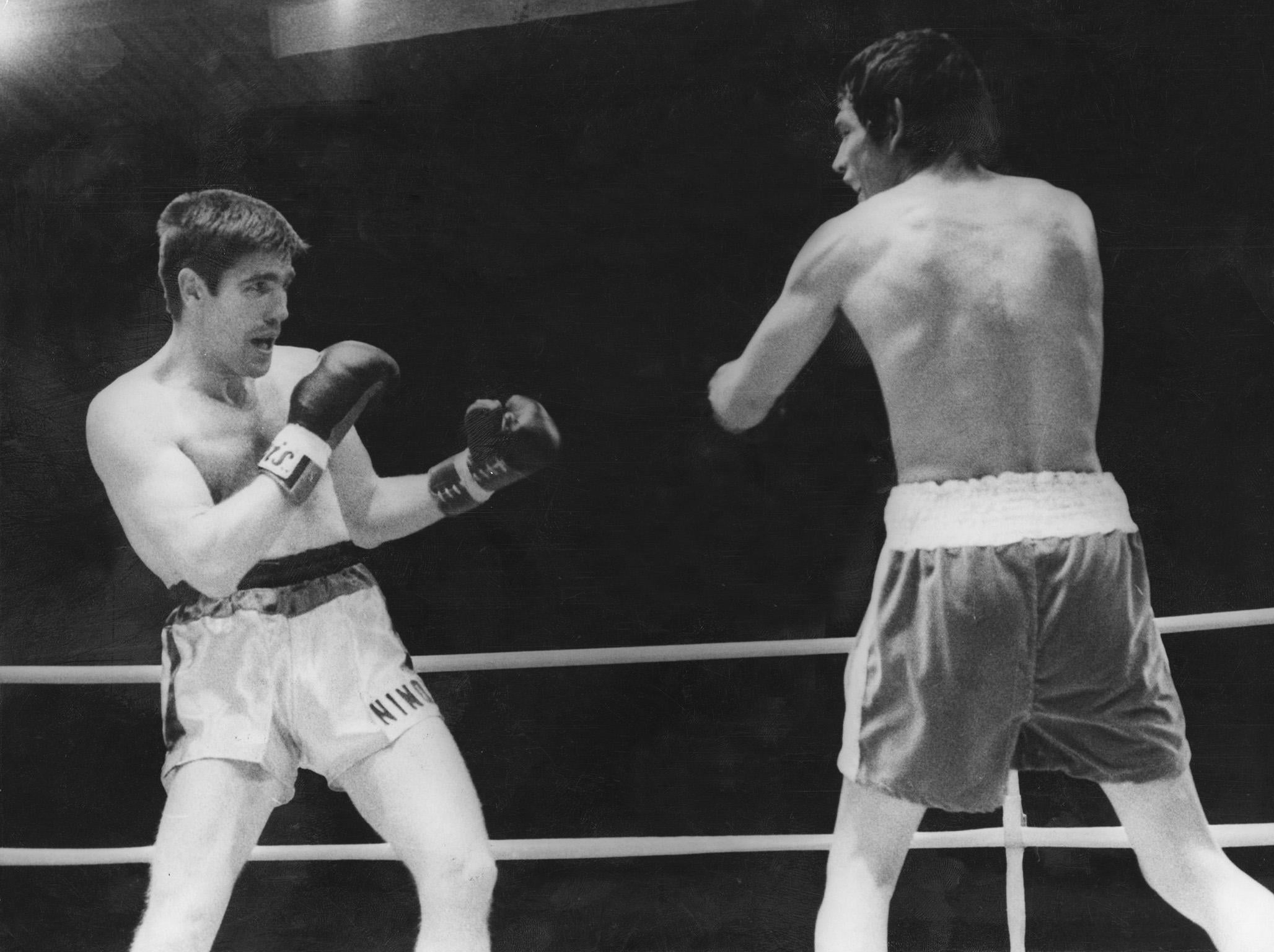

He finally won the world middleweight title in his 80th bout, another boxing fact that will never happen again, when he travelled to Rome to fight the Italian playboy and fighting hero Nino Benvenuti, gold medal winner at the Rome Olympics and a man that is treated like a deity in Italy to this day. It is too easy to dismiss sweet Nino as a playboy, he was far more than that and having worked alongside him at several Olympics he remains a courtly gentleman. Benvenuti is a fighter from a noble time, a reminder of a sport captured in faded colour films that never quit your memory.

It was nasty that night in 1970 and Monzon had death in his heart after Benvenuti pinched his bottom at the weigh-in. It was a calculated risk and it never worked: Monzon knocked Benvenuti out cold in round 12 of 15, a sickening right hand dropping the Italian in a still heap. He did it quicker six months later in Monte Carlo in his first defence of the world title; Monzon would make 14 defences in total, beating every single number one contender during a seven-year reign of utter terror. Monzon was a rare beast in the ring, a calculating boxer with enough deception in his movement to confuse the finest opponents before ruining their ambitions. Monzon won 10 of his 15 world title fights by stoppage or knockout and I would argue he was not fed one easy touch. The 70s was a truly unforgiving decade in the boxing ring.

“Monzon destroyed you little by little,” Angelo Dundee told me one afternoon in Tokyo. “I studied him before the fight and was confident my guy was slick enough – I was wrong. Monzon did a job.” Dundee’s ‘guy’ was world welterweight champion Jose Napoles; the fight was near Paris and Monzon won in six rounds. The French adored Monzon, even when he was brutally dismantling their finest, and he had seven world title fights there.

In 1974 he was stripped of one championship belt in an early act of stupidity by a sanctioning body and then secured his legacy by twice beating the “other” middleweight world champion, Rodrigo Valdes, in back-to-back 15 rounders in Monaco before retiring in 1977. He left the sport after 100 fights. His turbulent private life as Argentina’s number attraction could now continue without any interruptions for training camps.

After he was sentenced for killing Muniz his notoriety increased and Mickey Rourke, at the time a professional boxer, took a film crew to the prison for a sparring session. Monzon was 50 when he knocked out Rourke, leaving the wannabe slugger unconscious; Rourke’s hired hands soon sold the footage. In 1995 Monzon died in a car crash after a home visit, one of many. He remains both a violent, flawed idol and one of the greatest middleweights in history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks