Remembering the great Les Stevens: A terrific fighter, an iconic trainer, and one of British boxing’s finest men

Beloved former heavyweight, who passed away on Saturday aged 69, touched and transformed the lives of countless hopefuls and champions alike at Pinewood Starr amateur boxing club

He was known as Big Les, boxer, trainer, father, granddad and the man at the very heart of a boxing gym for 40 years.

Les Stevens went to hospital three weeks ago, it was serious, he was in a coma, intensive care, but resisting every day; the boxing world sent short films of support; “pray for him” his fighting family asked. He died on Saturday, he was 69.

He was the man in the corner at the Pinewood Starr amateur boxing club, the big man with a sponge, a spray gun of magic water and the right words for novices and experienced seniors. He also had a shoulder for a six-stone boy of 11 to cry on when he lost a fight. He turned out champions, he made better men and he helped shape a community. Big Les was an old-fashioned rock.

And Les Stevens could really fight, I mean really fight.

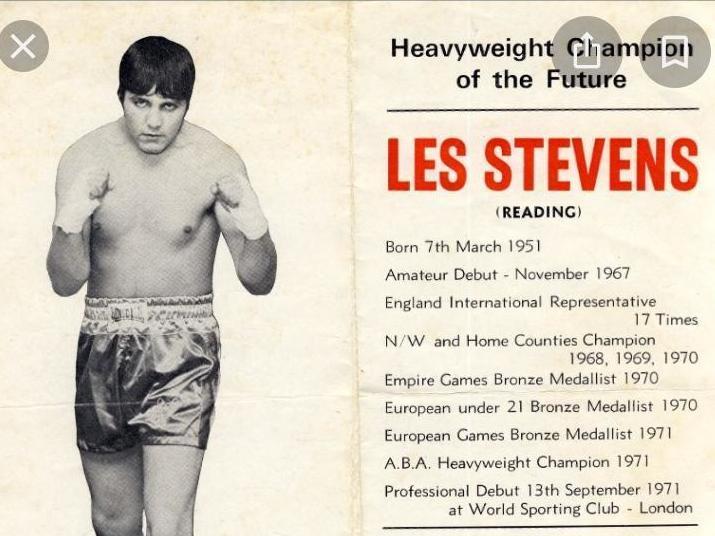

When he was just 18 he was representing England in international matches and when he was 19 he was part of a GB touring party to America, a team that included future world champions Alan Minter and John Conteh. Stevens was the baby in the team, but he won and lost in fights against men.

In the summer of 1970 he went to the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh and won a bronze medal, and that same winter he travelled behind the Iron Curtain to Miskolc in Hungary and won a bronze medal at the inaugural European under-21 championships. He was doing this, winning these medals as a heavyweight baby, not as a raw-boned giant.

In 1971 he won the British amateur title and completed a rare triple of medals at a major tournament when he won a bronze at the full European championships in Madrid. Stevens was just twenty when he got back from Madrid. Ten weeks later he lost the vest and turned professional at the World Sporting Club in London’s Park Lane; the kid from Reading won that night and he had the look; that Elvis Presley look, a proud traveller look. He had a fearless look.

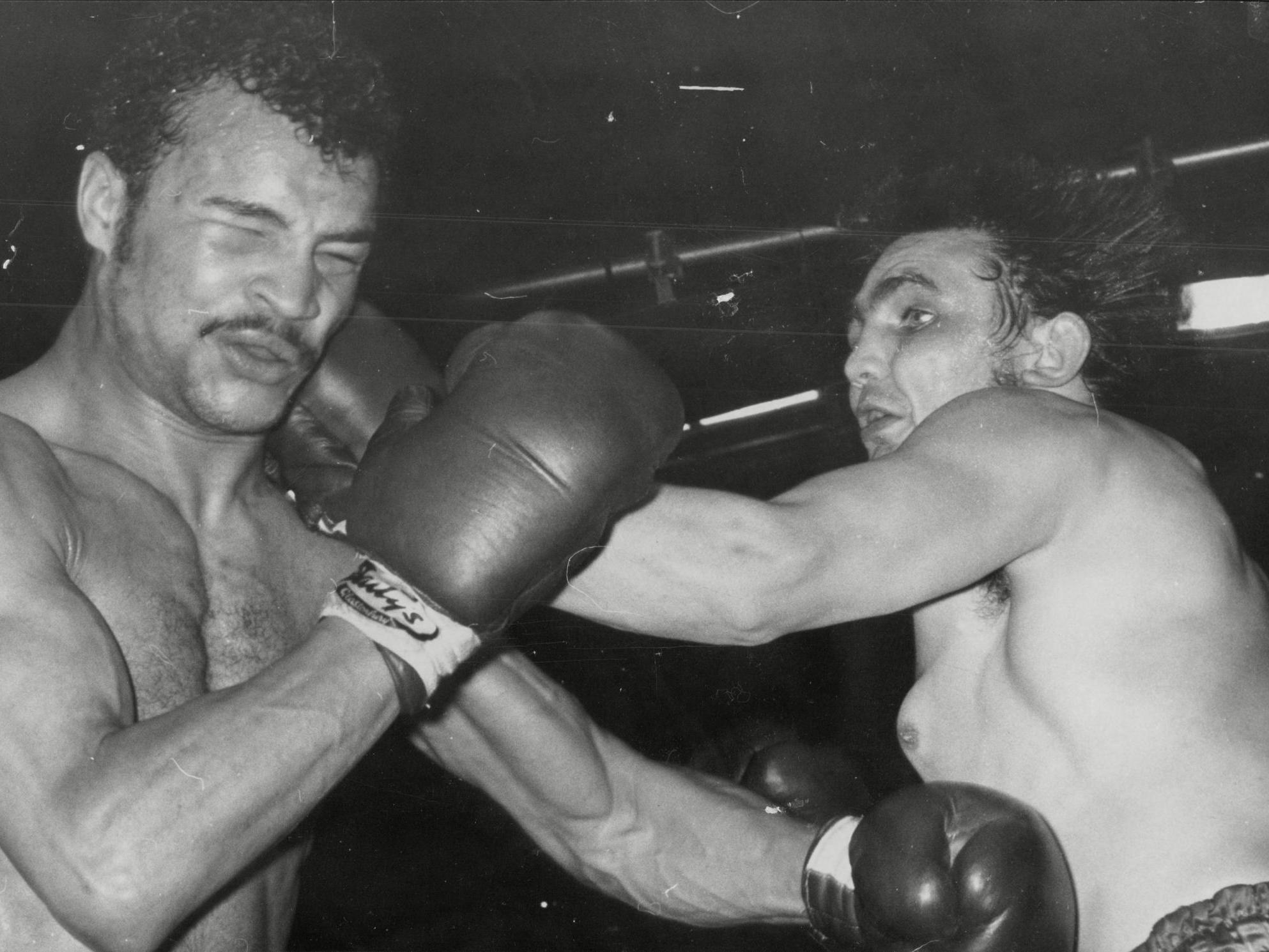

He fought hard men, men that growled, the men that filled the circuit in the Seventies and Stevens was as hard as them even if he looked like a boy. He went on a winning streak of 15, rare at the time, before a gash over his right eye forced a stoppage loss in 1973. He beat infamous scrappers like Dave Hallinan, Lloyd Walford and Rocky Campbell; they were men that lost, but never surrendered on any given night.

He lost an eliminator for the British heavyweight title to Bunny Johnson over 10 rounds at the Royal Albert Hall in 1973; Johnson would win the heavyweight championship and then drop down and take the light-heavyweight version, the only boxer to ever pull off that unique rare double in that order. The following year Stevens was back at the lovely old hall to lose on points over ten rounds to Conteh. A few months later, and a few pounds lighter, Conteh won the world title. The two remained friends.

Just six weeks later, Stevens, who never once weighed a pound above the modern cruiserweight limit, lost on points to Jimmy Young. It was a ten-round heavyweight fight, a hard, hard assignment for a British fighter. Young, you see, was a great fighter, an avoided fighter, a top, top operator and would beat Earnie Shavers later the same year. Young would then beat Ron Lyle, go the full fifteen rounds with Muhammad Ali in a world title fight and then send George Foreman into a 10-year retirement. Stevens went the full 10 with Young and that is real currency in the heavyweight realm of the Seventies.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

He retired from professional boxing in 1979, finishing with 23 wins and just five defeats. And then he became an iconic figure as the man in the corner at Pinewood Starr, the trainer of champions, as many as 200 over a nearly 40-year period in the gym. That is a life devoted, dedicated to helping others and there is no cash incentive, often no glory and no hype for trainers in amateur clubs. He transformed men and boys and not just the champions, and did it without fanfare. However, a man like Big Les is never an unsung hero. The people he helped – maybe even saved - know what he did and he is never overlooked in their mind.

There are so few true boxing men like Les Stevens left. He will be missed by so many and never forgotten when boxing people gather. Never, no chance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks