Muhammad Ali exhibition serves as a timely reminder that his story is still painfully relevant

More than half a century after he first landed in London, Muhammad Ali returns to the English capital, not in person but in the form of an exhibition celebrating his career in the ring and his life out of it.

In a month when those great, white-washed beauty contests, the Oscars in America and the Brits here, were forced to assess how they represent ethnic diversity, Ali’s story is still miserably relevant.

The exhibition mirrors the permanent installation at the Muhammad Ali Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, once a key trading post in the trafficking of black flesh across North America, and the city where Ali was born and raised.

Boxing provides the context. Magnificent though his contribution to the sport was, his talent for throwing leather at his fellow man was not necessarily better than that of Jack Johnson, Joe Louis or Sugar Ray Robinson. Ali’s significance lay in the remarkable political stance he took amid the seismic black civil rights struggle in Sixties America.

Ali’s significance lay in the remarkable political stance he took

These days the pens in which black slaves were corralled, paraded and sold on Louisville street corners are marked by plaques across the city. When Ali was a kid learning to box as Cassius Clay, America was still in the grip of apartheid policy, divided and fractured. There was no civic recognition via place names of the wrongs committed by a political class that built prejudice into the state apparatus. Clay experienced structural racism at every turn.

The museum in Louisville offers a real sense of this as well as detailing beautifully his artistry in the ring. The exhibition in London offers a flavour of both, too.

It is difficult now to convey the scale of Ali’s fame to an audience saturated by sports coverage that delivers forensic detail live in 360-degree perspective. His first showing against Henry Cooper at Wembley in 1963 drew a crowd of 40,000, which included the Brad and Angelina of the day, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, at ringside. We can assume they had not come to see our ’Enery.

The gloves worn by Clay that day, slit by trainer Angelo Dundee to buy time at the end of the fourth round after Cooper had floored his man, form part of the London exhibit, as does the stopwatch that ticked for at least an extra minute.

An appearance on Parkinson, the eponymous talk show hosted by Michael Parkinson, was an impossibly exotic visitation in the age of the sports highlights reel. There were hardly any live broadcasts in those days. The fact we saw so little of him made any exposure something to treasure.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

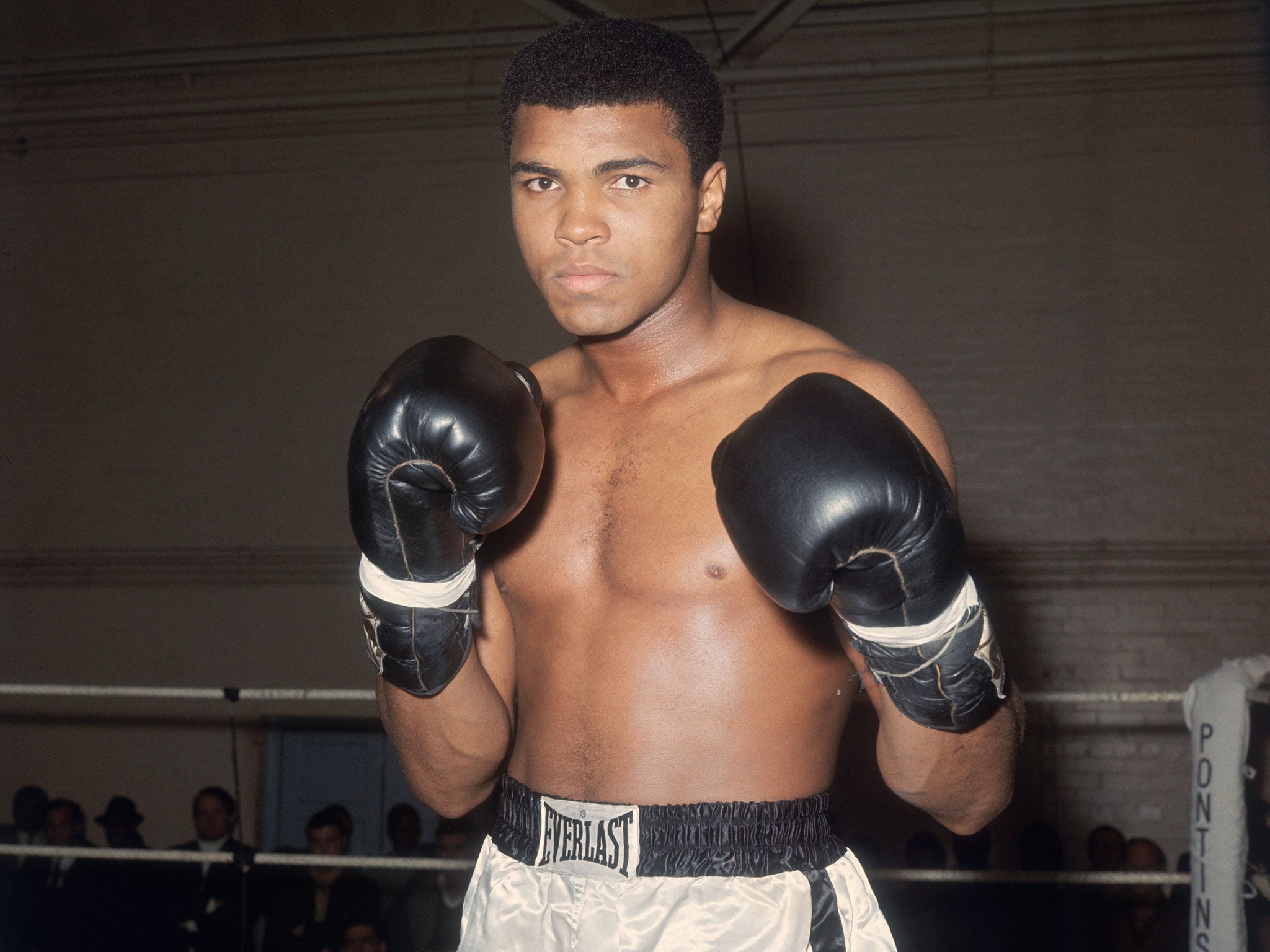

Thus stars like Ali grew in our imaginations. We added and filled around the edges in a process of deification, so that the man became otherworldly. The dazzling figure in the ring, the golden Olympian of Rome, the conqueror of the fearsome Sonny Liston, so handsome, athletic and articulate would have been beguiling enough, but the political dimension moved him on to an entirely different plane, a bruising, passionate advocate of social change that tore at the certainties propping up the Establishment.

“No Vietcong ever called me nigger,” was his celebrated justification for refusing the United States military draft to prosecute the Vietnam War, a sentence way more powerful than any punch he ever threw. The authorities recoiled, stripping him of the world title and sending him into exile for three years. Thus was he made a martyr for his cause, a mighty symbol of injustice, and an international celebrity.

When Ali returned in 1970 the world could not get enough of him. Some of his most memorable performances followed, cementing his place in the pantheon. The trilogy with Joe Frazier, the split-decision duels with Ken Norton and, of course, the epic night in Kinshasa when he somehow eclipsed George Foreman to win the heavyweight title for a third time, a first for the sport. The gown worn by cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown at the Rumble in the Jungle also forms part of the exhibition.

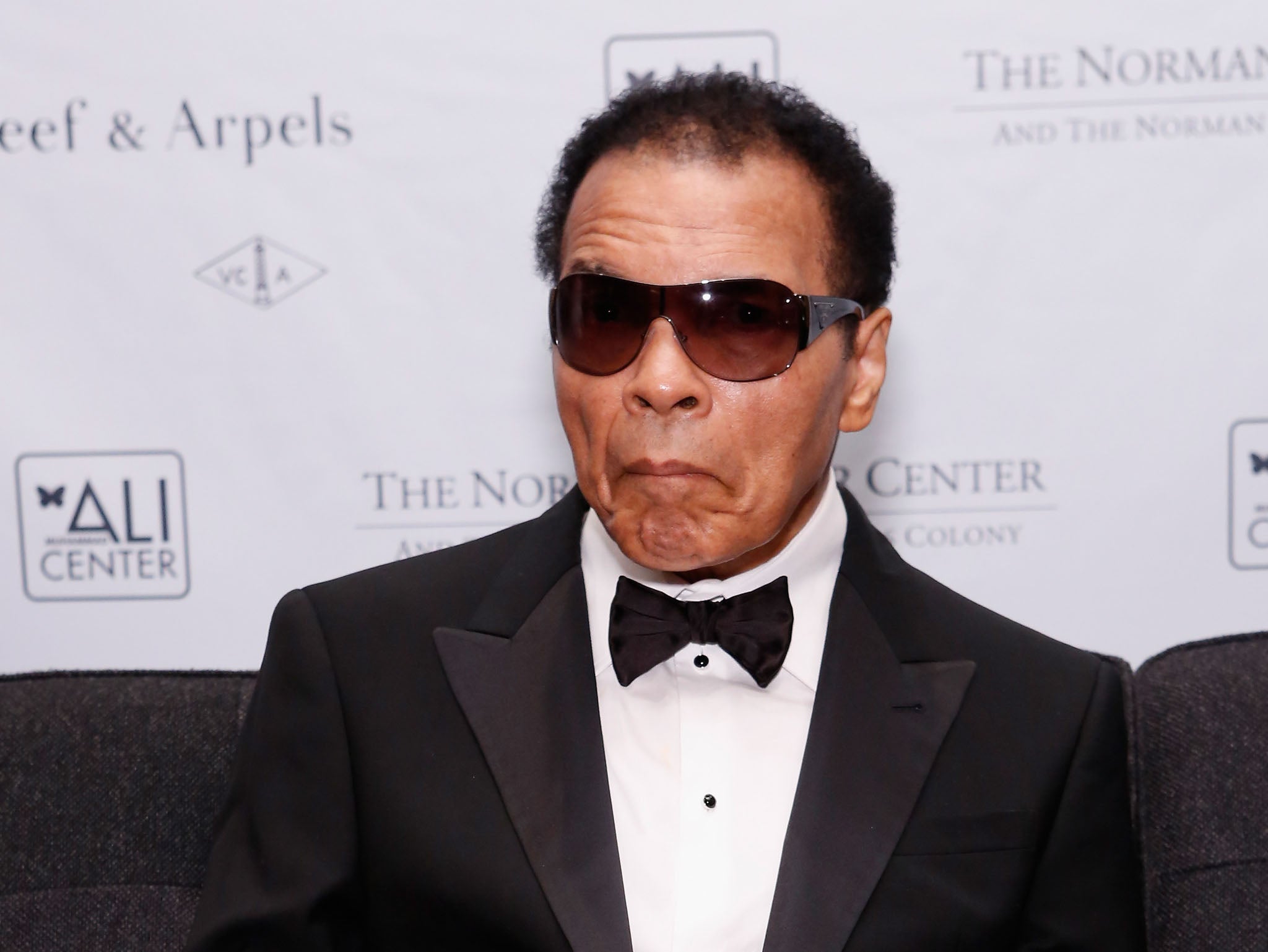

At the close of the decade Ali was fully rehabilitated in the sports community, his days on the barricades over. Parkinson’s disease would later creep upon him to diminish that remarkable physicality and still that waspish tongue. He is seeing out his days in Arizona with his fourth wife, Lonnie, his legacy cemented and his relevance maintained by the continuing inequality faced by black and ethnic people in the Anglo-Saxon world.

The prejudice is more pernicious half a century on, not so easy to identify in the epoch of the righteous do-gooder preaching political correctness. As Chris Rock put it, in skewering the white elites running Hollywood in his address at the Oscars, or “White People’s Choice Awards”, as he described them. “Is Hollywood racist? You’re damn right Hollywood’s racist … not burning-cross racist ... it’s a different type of racist.”

Enjoy the show.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks