James Lawton: D'Oliveira, the quiet hero whose life was a battle for decency

The sound of Die Stem was a jarring memory as Mandela embraced Pienaar in 1995

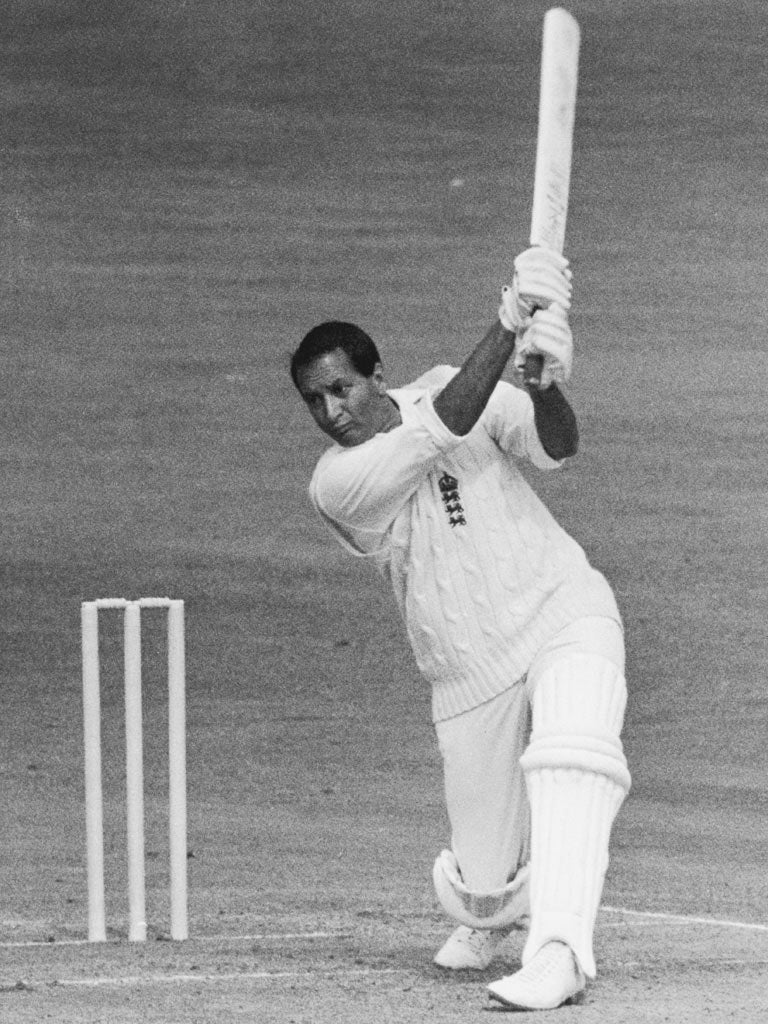

Basil D'Oliveira's life was of such understated heroism and unforced dignity, had such brilliant wide-ranging effect, that when it came to an end this last weekend there might have been an inclination to soften the hard edge of its drama.

We might have seen it not so much as a battleground as a softly stated appeal for decency.

We might have seen it as the triumph of a man who helped shape huge, civilising steps for humanity simply because he played cricket superbly well and just happened to have a little more enterprise, and mobility, than so many of his more resigned fellow victims of apartheid.

But then we couldn't have strayed much further from a reality that even now, 40-odd years after its most vital expression, is nothing less than stunning.

D'Oliveira wasn't a propagandist for a great cause, a natural-born rebel. He was a man like any man, but then he was also one who knew right from wrong and, in the end, the injustice he suffered every day, going about his work and walking 10 miles to play cricket on surfaces that would have been sneered at by players of vastly inferior ability but who just happened to live in a more conveniently coloured skin, could no longer be borne.

Not without an unbearable frustration – and an overwhelming sense that he could no longer accept his harsh, arbitrary fate.

The story of D'Oliveira is, of course, a foundation stone of the battle to break apartheid.

We know well enough how he elicited the help of the great cricket writer John Arlott, who found him a first post in the league cricket of Lancashire, and of the threats of the South African government and the compromises of the MCC when he later demanded to return to his homeland as a member of the England team with a brilliant century against the Australians.

What might not be so easy to reconjure now is the ferocity of the inhuman system he so calmly defied and undermined as South Africa was pushed into 20 years of international sports isolation.

It is a task, though, somewhat less challenging if you happened to be at Ellis Park in Johannesburg when the All Blacks returned in August, 1992, to play rugby there in one of the great Boer citadels for the first time in 16 years. Then you had a measure of the force that Dolly, safe now in his new home coaching youngsters and minding his family in Worcestershire, had taken on and beaten.

It wasn't a losing political theory you felt all around you that day at Ellis Park. It was one of the last undiluted outpourings of a working belief that the nature of your life should be determined by the colour of your skin. There were, as Nelson Mandela was already deeply involved in the inexorable process of taking over the reins of power, not so many black men and women in the great stadium that day. Of those that were, the most visible carried cleaning pails and brushes and on the official benches it was just possible to see a few token representatives of the African National Congress. South Africa, we were being told as the barriers of boycott began to fall away, was turning its back on apartheid. And yet when the call was for a minute's silence, perhaps to remember the pain and bloodletting of all those desperate years, the stadium was filled with something quite else.

It was the sound of "Die Stem", the Boer poem turned national anthem which had long been a source of bitter resentment by the non-white population. "Die Stem" crashed across Ellis Park in great waves of passion and that was something that three years later would be the most jarring memory as Mandela donned his Springbok jersey and embraced the winning South African captain, Francois Pienaar, in the moment of World Cup victory in the same stadium.

Last year Ellis Park, the old fortress, was, of course, afforded a less prominent position in another World Cup, when the spectacular Soccer City stadium, fashioned in the shape of an African cooking pot, drew the eyes of the world when Spain beat the Netherlands in the final.

We might, when you think about it, have given the achievement of Basil D'Oliveira a little nod of recognition in those tumultuous days when non-white South Africans, so many still, it has to be said, way down the financial pecking order, were able to go where they pleased and celebrate the great sports party wherever they chose.

Going back through the life of the fine cricketer these last 24 hours or so is to be reminded of a man who understood more than anything that he had one life, one talent, and that however hard the pressure, however alien the environment his destiny found for him, he had an obligation to do all that he could to make a different kind of life for himself and his family.

The terrors of his new existence can only be imagined now – along with the strangeness of not being herded into stadium cages or certain parts of a bus or a park and the headiness, when he had overcome the huge challenge of playing on uncovered grass pitches rather than "mounds of mud", of being invited to a restaurant by his new admirers in Lancashire and then Worcestershire.

In his tribute to D'Oliveira, Peter Hain, who fought so passionately for the boycotting of apartheid-bound South Africa, makes the telling point that while the hero never enlisted in any campaign, he made out of his life an irresistible case for those who said that the time of compromise had passed.

We may say that it is work that can never be said to have been truly done, and that the beast is at best in repose, but if there is reason to be exercised by the recent eruptions of racism controversy, there must also be encouragement both in the new levels of vigilance and the recognition of quite how far the world has moved from the issues which threatened the existence of a man of achievement like Basil D'Oliveira.

There was a time when you could tour the wind-scoured rugby fields and cricket pitches of his native Cape country, set on hillsides and all kinds of rough ground, with goalposts tilting on hillsides, and wonder what kind of spirit could drive on young sportsmen of talent but so little practical encouragement. It was, we learnt some time ago, the self-belief of a young man who went to a foreign place armed only with an idea that if he fought hard enough, if he kept faith in who he believed he was and might one day become, he might just bring a little more sanity – and decency – to the world.

That now will always be the epitaph of the quiet, handsome man from Cape Town who believed there was another way to live, another way to use the gifts with which he had been so bountifully endowed. In the end, he produced the force and the character to silence the prejudice that might have ruined a life less filled with courage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks