Euro 2016: Why a deep sense of injustice is making it hard for Karim Benzema's home city to love the French team

France's most talented striker is absent from their European Championships squad. What is at the core of the controversial frontman?

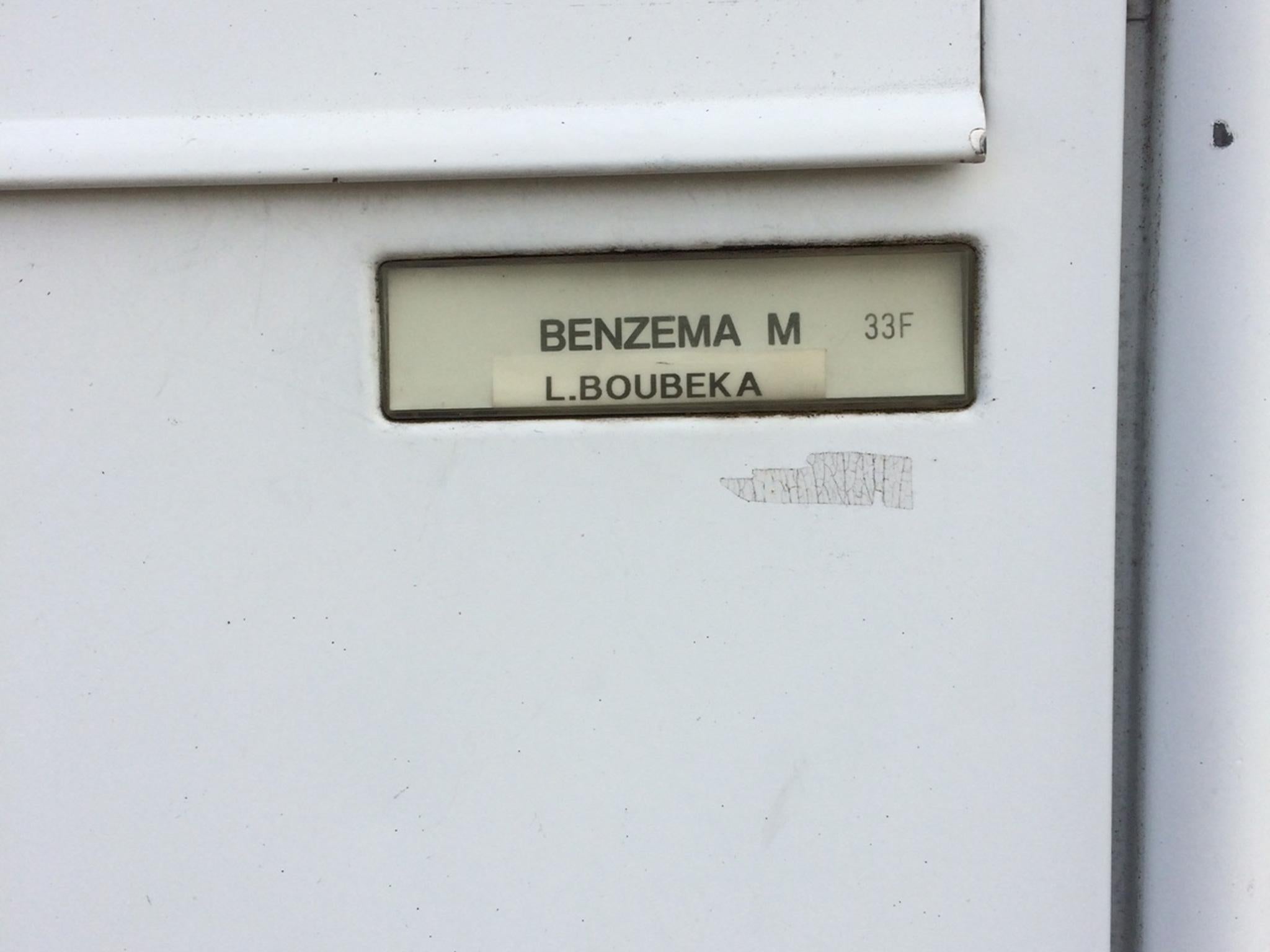

The letterbox at 33F Rue Marcel Cerdan tells its own story of how Lyons and Karim Benzema are inextricably bound up.

It states in small letters – Benzema M. - that Malika and Hafid Benzema, the parents of France’s most discussed footballer, live here. Yet the house it belongs to is a careworn place: faded orange paint on the rendered walls, precious few windows and a poky front door. Players tend to move their parents out of unprepossessing working class dwellings like this when they’ve struck it rich like Benzema, star of Real Madrid, and apparently he tried. They say Mme Benzema wanted to stay where she felt she belonged, though, in the district of Bron-Terraillon, six miles out into the suburbs of the city where France play the Republic of Ireland in the first Euro 2016 knock-out round this weekend. So her son still calls by sometimes and still calls this place home.

Benzema is an individual whose story absorbs and obsesses France. He keeps the company of Cristiano Ronaldo and Gareth Bale in the Real Madrid front line, yet is absent from Didier Deschamps’ European Championship squad because of a story of inconceivable sleaze: an alleged plot to blackmail France team-mate Mathieu Valbuena which may come to court later this year.

The search for the core of Benzema is complicated. The received wisdom tells that he is a lost child of the French banlieues, with Bron-Terraillon depicted in that narrative as one of the worst: a French Bronx, infested with gangs, drugs and juvenile delinquency. On a Sunday afternoon in high summer, this is quite plainly not true. The neighbourhood is not riddled with delinquency. North African French boys gathering in the car park of the football club where Benzema – ‘Coco’ as some of them know him - first played are boisterous but there is no ominous air of suspicion. A police car patrols but the windows are down. It's not a no-go land. Bron is not about to blow.

Benzema evidently remains an intermittent part of life here, still slightly awkward in private company after whichever ostentatious sports car he happens to be driving has pulled up outside the corner house in the terrace on Rue Marcel Cerdan, according to the Benzemas’ next door neighbour Alvarde Torossiane. “It is strange to know someone who has a big profile. There is a distance between the profile and the person,” she says. “He is not someone who is an extrovert. It is not the same as they describe him. He has an attachment to this place.” Benzema’s sister Nafasia is her close friend but they all knew each other and shared the long empty afternoons together on the road outside when they were younger, she says. “When he was not a player the family was not rich and you don’t forget that,” says Mselle Torossiane, who is four years Benzema's senior. “You remember what it is to be poor.”

Inquiries about Benzema here also elicit much talk about la mosque and people point back towards the part of Bron where you are deposited on the complicated journey out from Lyons, which requires two buses and a tram. They all say Benzema, whose family are of Algerian descent, paid a substantial amount to help rebuild the mosque, evidently not wanting publicity. A group of women there confirm the story but say the men of the place will be able to talk. They don’t materialise.

The taxi driver, Azedine, the fifth person to mention the mosque and of Algerian origin like the Benzemas, attributes the decision to exclude Benzema from the squad to a distorted kind of French morality. “Il fait de betises. Il est jeune” (‘He does stupid things. He is young’) he says. He launches into what he claims to be the evidence of a double standard at the heart of the decision: the case of France handball player Nikola Karabatic, who was found guilty of match fixing in 2012 and yet still was selected to play for the national team which subsequently won the European Championships. Benzema has been found guilty of nothing, the driver says. “The politicians enjoy this. They take the publicity and they moralise and they think it makes them look good.”

Benzema stands accused of something considerably more serious than fixing a handball match that attracted €103 in bets. When a video of Valbuena having sex made it into the hands of one of his entourage, four people, including him and his Bron-Terraillon childhood friend Karim Zenati, were accused of demanding £100,000 from the player, in return for not releasing it into the public domain. Benzema denies any wrongdoing, though his arguments were undermined when Valbuena spoke about the player’s attempts to pressurise him. He told a French newspaper he was particularly shocked by the way Benzema spoke about him over the phone with one of the suspected blackmailers, joking that Valbuena would get "eaten by the piranhas." Benzema acknowledged that the tone of his conversation - after his phone had been tapped by police investigators - was uncalled for and apologized to Valbuena.

The scale of the saga reached new proportions when Benzema’s exclusion from Deschamps’ team last month brought the incendiary suggestion from Eric Cantona, among others, that racial prejudice lay behind it. It was a claim Benzema seized on. “He has bowed to pressure from a racist part of France. You have to know that an extremist party reached the second round in the last two elections in France,” the player said of Deschamps.

The notion of incipient racism at the French Football Federation does not stack up. The North African representation in Deschamps’ squad proves it and even in the old multi-cultural district where he played in the streets they just can’t see it. “It is not racism that keeps him out of the teams. It is the problems of the case,” says Ms Torossian. Kosh Higo, who is North African French, shakes his head at the notion.

But what does puncture the sense of enthusiasm for Deschamps’ team being in Lyons this weekend is the widely held conviction that football is being used to promote a politically inspired moral crusade. The politicians have been falling over themselves to have their say on the player in question. President François Hollande emerged from an evening with Deschamps’ team at its training centre to say, in the context of Benzema’s exclusion, that it “not only must play the best football, it also acts as a role model.”

The French Prime Minister Valls continued, insisting Benzema should not be in the side because a “great sportsman must set an example.” Benzema responded with a tweet to that one. “I have been a professional for 12 seasons!!! 541 matches played, 0 red cards, 11 yellow cards. And some question the example I set???” There were even polls on the subject of Benzema’s eligibility for blue shirt, in what became ‘“une affaire d’état” leading into the tournament.

Benzema happens to be a role model for the wrong kind of people. He appeared last month in a video accompanying the song ‘Walabok’ by the French rapper Booba, leaning moodily against a wall at the end of a five-minute film largely devoted to a singing about drugs and shootings and holding firearms. This was a source of fascination to a specific French sub-culture, given that Benzema had previously been allied to the rapper Rohff, whose Benzema videos feature him scoring goals rather than celebrating saw-off shot-guns. Booba and Rohff are thought to be sworn enemies. The Booba alliance looked like a leap into the dark side for Benzema.

This is a player who has known more than his share of criminal allegations, too. He was handed preliminary charges for soliciting an underage prostitute in 2010 but acquitted in a case that lasted more than three years. The FFF view is that after the state of civil war which engulfed the French South Africa World Cup, they do not want the discord within the squad that a player accused of blackmailing a teammate might bring. As things transpired, Valbuena also missed the cut — but for footballing reasons after an under-par season.

The struggle among some to see things the federation’s way is tied up with the fact that few in France are convinced about the team or Arsenal’s Olivier Giroud, who has the starting place Benzema had thought might be his. “Faut-il croire en eux?” (‘Should we believe in them?’) the cover of this week’s France Football asks about the host nation side and the uncertainty about Giroud reached extraordinary dimensions heading into the tournament.

The Arsenal player’s name provoked whistles and jeers during France’s warm-up matches against Cameroon and Scotland in France. Giroud publicly acknowledged that the jeers come in part from those who think that he was chosen only because Benzema was excluded. “Life is complicated at the moment,” Giroud told reporters after the 3-0 win over the Scots in Metz, 20 days ago. Fans treatment of Giroud was unfair, but “people can be conditioned,” Deschamps said at the time.

It hasn’t helped the sense of injustice in Lyons that Giroud was himself the subject of disciplinary action in February, when forced to apologise for taking a female companion back to the team hotel. In his taxi, Azzedine, is well acquainted with the story of Giroud, Celia Kay and London’s Four Seasons hotel before Arsenal’s match with Crystal Palace. ‘C’est la betise humaine,” (‘It’s human stupidity’) he said, insisting that Benzema should be no more harshly judged than Giroud, since he has not been found guilty of a crime yet.

On Benzema’s street, Giberklou Romain cites the Booba alliance as a significant factor in this saga. “It’s about the videos,” he says. Alvarde Torossian says that it is the general portrayal of her once next-door neighbour, rather than his omission from a football squad, that she takes issue with most. “I don’t understand the reason Karim doesn’t play,” she says. The image in the media is not the same as the reality I know.”

What seems most missing in his life is someone to take on the role of Malika and Hafid Benzema when he is far away in the bright lights of Madrid. It was Jose Mourinho who saw the need to get some sense into him. When he turned up a manger at the Bernabeu in July 2010, he found a striker who was timid, lazy and unreliable. Somehow he struck a chord. “If I can't go hunting with my dog then I will have to take the cat," Mourinho told him ahead of one game for which when first-choice striker Gonzalo Higuain was ruled out and Benzema had to play. Soon, he was scoring goals like there was no tomorrow.

A few hours before confirmation of his elimination from the French team, Benzema reaffirmed his commitment to Deschamps’ side. "Quoi qu'il arrive, Bleu un jour, Bleu toujours" (‘Whatever happens, once a Blue, always a Blue’), he tweeted to his vast following. Many see him as sinned against as well as sinner. It is because of Benzema that some will struggle to summon much love for the national team on Saturday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments