After 150 years the truth: Scotland invented football

As Wembley prepares to host the Auld Enemy once again with a friendly for the FA's anniversary, it is time Patrick Barclay put the record straight

In the days before political correctness it used to be said that, while the Irish could take pride in the invention of the lavatory seat, it was the English who had come up with the bright idea of carving a hole in it.

So the joke really ought to be on the English this time as they continue to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the invention of organised football with a match against Scotland on Wednesday. It was the Scots who truly devised the game as we know it. Without their civilising intervention, what England might have given the world was just another version of rugby.

When the so-called Football Association' was formed at the instigation of Ebenezer Morley, a young solicitor from Hull who lived by the Thames in south-west London because rowing was among his sporting interests, what he proposed would be seen now as a basis for rugby with extra violence.

Morley's draft laws provided that a player could not only run with the ball in his hands but that opponents could stop him by charging, holding, tripping or hacking (kicking him on the shins) and initially a majority of the delegates at the historic meetings in the Freemasons Tavern agreed.

Fortunately progressive elements rebelled and, after a more civilised code emerged, the delegate from the Blackheath club – outlaw hacking, he had presciently warned, and such would be the loss of "the pluck of the game" that the French might even prevail at it – harrumphed away, eventually to help to form the Rugby Football Union.

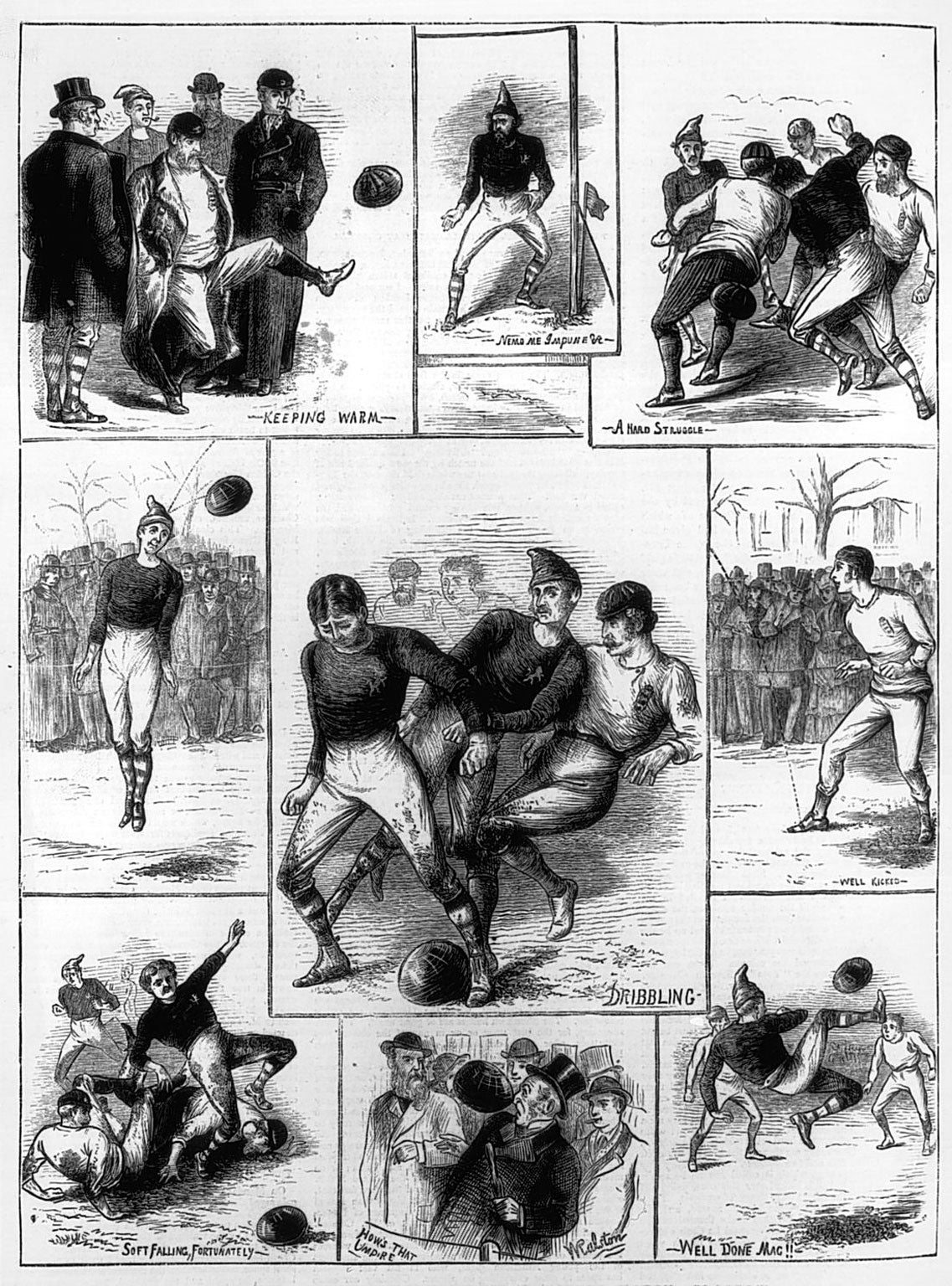

However, the English game was still mainly a question of head-down dribbling and "backing up" (by colleagues anxious to seize what was later dubbed the "second ball"). This was not a game which would have conquered the world with its beauty.

And then the Scots had the notion of artfully distributing the ball among the players. It started with young men, from Perthshire and the Highlands mainly, who gathered at Queen's Park in Glasgow in 1867. They obtained a copy of the FA laws and amended them to conform with an almost scientific blend of dribbling and passing.

When they invented passing, these lads invented football. Not the heir to Shrove Tuesday scrimmages but the football that was to charm every continent. Far from being an English game, it was one that was conceived to confound the English because the Scots, being generally smaller than their opponents in football's oldest international rivalry, could hardly afford to take them on physically.

Thus we had the Scots' "combination game", the original pattern from which everything worthwhile in football – from the mid-European flair that culminated in England's humbling by Hungary at the old Wembley in 1953, to the 1970 Brazilians, to the Barcelona of Pep Guardiola – has been designed.

It even worked for the Scots for a while. They were the original world champions, albeit unofficially, for although the first international, with Queen's Park representing Scotland in Glasgow in 1872, ended goalless and England won the next in London, the Scots won 10 and drew three of the ensuing 14.

Then the Football League started. Preston North End, dominated by Scots, became its first champions in 1889. Indeed they did the Double. The next club to do it were Aston Villa eight years later. Villa had been transformed by a Scottish manager, George Ramsay, who had taught them to pass – their previous approach he later described as "a dash at the man and a big kick at the ball" – and a great Scottish player, Archie Hunter.

Ramsay and Hunter inspired Villa to take five of the last seven championships of the 19th century and were the most successful of the imports from north of the border, being hailed all over England as footballing academics come to educate the natives: the "Scotch professors".

Even now the memory of outstanding Scots – at least in management – has hardly faded and right up to the prime of Kenny Dalglish, arguably the last of the professors (although a counter-argument in favour of Gary McAllister would be accepted), the country led its big brother in the ancient international series.

England did not move ahead in terms of overall wins until goals from Bryan Robson and Gordon Cowans sank the Scots at Wembley in 1983. But six years later, when the series was abandoned, it was amid mutual relief: the English were bored and the Scots, by now struggling with the likes of Luxembourg and Cyprus, feared increasing humiliation.

At least this week, however, they can feel pride. To have the English borrowing their history is quite a compliment – and to be invited to share it perhaps the best joke of all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks