Comment: Why clubs must take the blame for mercenaries like Luis Suarez and Wayne Rooney

There has been a loss of collectivism when pay is concerned

The excellence of David Peace’s novel Red or Dead resides in its incidental, long forgotten details about Bill Shankly’s socialist form of football.

Such as the collective grievances of his Liverpool players who, as some of the First Division’s lowest-paid stars, were denied their customary “crowd bonus” after reaching and winning the 1965 FA Cup final – because that money, paid for home and away games, was not deemed to be due for games held at a neutral venue.

Shankly spoke up for his men and got them their bonus, though he was unsettled by the whole business. “Bill Shankly didn’t like money,” Peace writes. “He didn’t want to talk about money, he didn’t even like to think about money. Bill Shankly knew you needed a roof over your head. Food on your table and clothes on your back. But Bill Shankly believed you had to earn your wage. Then you would cherish that roof. That food and those clothes…”

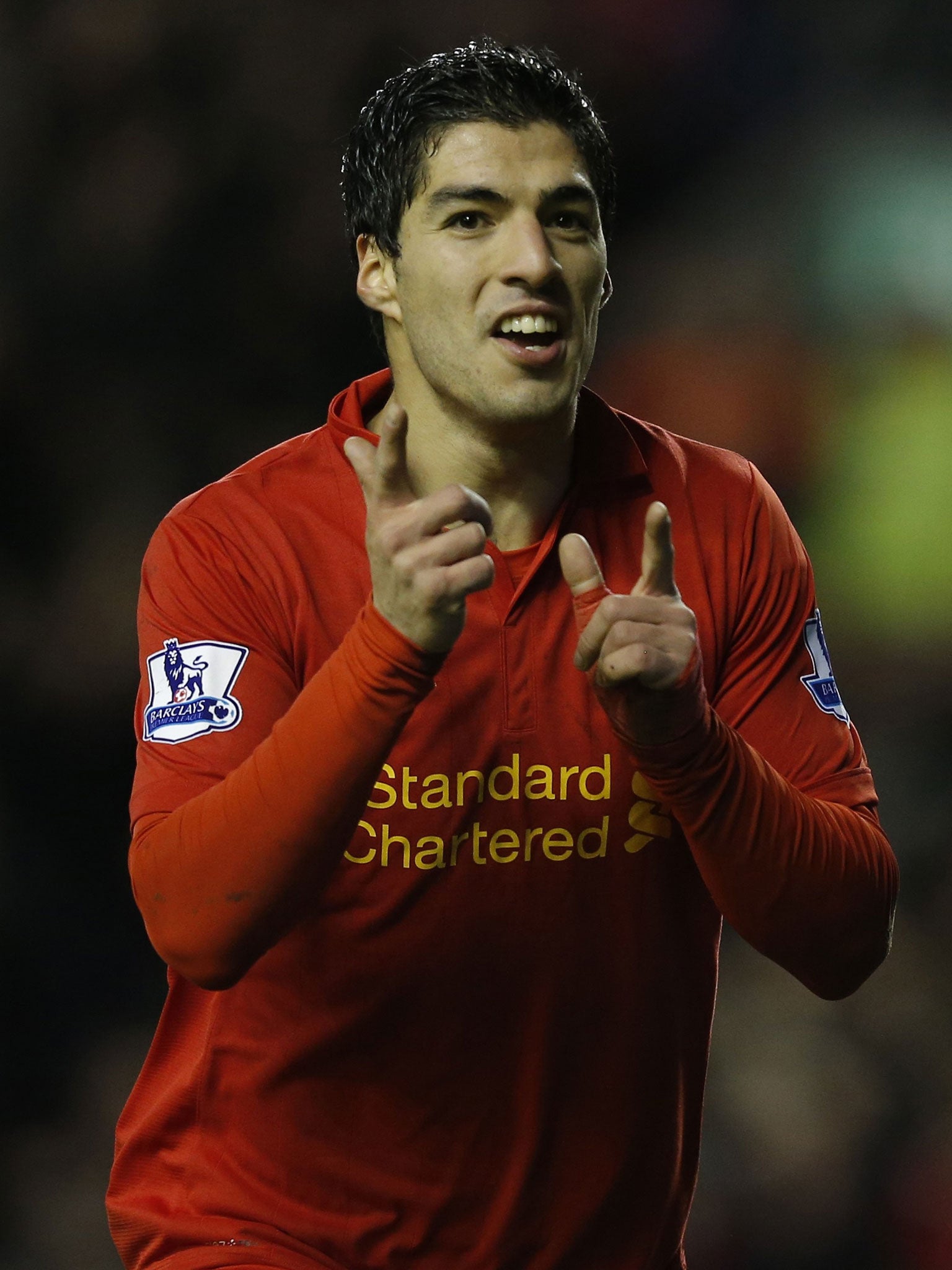

One of the reasons why we’ve ventured into the current Luis Suarez and Wayne Rooney swamp – and so very far from those Shankly days – is the loss of any kind of collectivism, where pay is concerned. John Barnes said last week that supporters were to answer for the way players are built into such superstars that they feel impervious to any kind of criticism when they decide to up sticks and go.

He had a point. You felt, when Luis Suarez got on to the field in Steven Gerrard’s testimonial at Anfield 10 days ago, played as fecklessly as he could, and still got some adoration, that he was perhaps seized with desperation about how to shake off these people. A day later he effectively told two newspapers that Brendan Rodgers had lied to him.

But the clubs have most of the answering to do, cutting each others’ throats as they do by bestowing the kind of contracts which leave managers hostage to the vagaries of these players. We already know that it’s a la-la land where clubs are so desperate for talent that they’ll pay players £250,000 a week.

But we’ve actually reached a place where, last summer, Jose Bosingwa’s agent tried to get Queen’s Park Rangers to agree a clause paying his client a £5,000 a week bonus if he was injured. The club respectfully told him where to take that suggestion but that is the place the sport occupies. “The more you want a player when you sign him, the more you are prepared to bend and incentivise,” says one insider who has been deeply involved in some of these club/agent negotiations in recent years. “When you get to the negotiation stage, some agents are demanding bonuses for everything and trying anything and some clubs are so desperate they agree.”

One manager who arrived in the Premier League to find his players’ bulky contracts dotted with bonuses for performances, appearances, assists and goals asked – not unreasonably – why his players needed to be paid for appearing, something he thought they had actually been signed up to do.

And that doesn’t even begin to account for the way the top players are allowed to syphon up to 15 per cent of their contract into image rights companies, which nurture the spirit of individualism even more.

Did we actually read last week that the Intellectual Property Office has allowed the number 11, inside a heart shape made of two hands, to be trademarked, possibly earning Gareth Bale up to £3m a year? Yes, that one really wasn’t made up.

The Suarez saga revealed the desperation of a football club in all its gory detail. There were Liverpool, so desperate to secure their man, with Juventus snooping around, in January 2011. And so they sprinkled a little stardust on the situation – player incentive here, agent incentive there – offered Suarez something vaguely defined to make him feel there was a way out. The club’s owners had the chance to put a stop to that deal and the clause which has now caused so much trouble. It was a new contract for their best player and they should have demanded to. They did not. Even the Professional Footballers’ Association, which is paid to look after Suarez, is unimpressed with the deal.

Sports lawyer Ian Lynam articulates extremely well how clubs, who throw anything from 60 per cent to 90 per cent of their turnover at salaries, are doing so with ill-conceived contracts which offer no economic incentives for loyalty. He points to Suarez’s playing statistics for 2012-13, with their high levels of activity but with a substantial number of failed dribbles, off-target shots and concessions of the ball.

“In particular, Suarez continuously shoots from wide in the penalty box, an area from which he has a very low success rate when compared to even an average Premier League player,” observes Lynam, from the Charles Russell partnership. Goalscoring incentives can make a player selfish and Lynam asks whether an incentive to pass the football could encourage Suarez to be more efficient in his play. That makes a good deal of sense, though Shankly would probably have expected the general contract to cover it.

Might not contracts also engender greater loyalty if a player got 40 per cent of a previous year’s salary when the transfer window closed? Ye’ is the answer to this and many other questions which football could tackle if only Premier League clubs could summon the Shankly spirit of collectivism. They could agree a clause in all player contracts to reduce all salaries by 50 per cent in the event of a club’s relegation. They could agree industry standards for pay and a top salary rate of £100,000. It won’t happen, though, because waiting around the corner is another Suarez, Rooney, Robin van Persie or Samir Nasri, whom two clubs will want to rip up the rulebook for when a bidding war starts.

The landscape is not entirely barren. Everyone inside football knows that West Bromwich Albion have become a beacon of sound, shrewd contracts under the chairmanship of Jeremy Peace, refusing to budge from a salary budget and incentives based on the club’s finishing position in the Premier League. Manchester City’s salaries have become substantially more performance-related, with major kickers for Champions League qualification. Arsenal’s have always been significantly back-ended, encouraging loyalty.

It’s worth stating that Shankly’s socialist world had its share of brutality, too. David Peace covers the manager’s casual dismissal of goalkeeper Bert Slater – who after 96 consecutive games never played again – and Jamie Carragher told me last week that a little perspective is required with players like Suarez, who are on a short professional lifespan. “I’ve seen plenty of players, with families, just getting offloaded from Liverpool, who haven’t wanted to go,” he said.

Carragher, who is as far away from la-la land as any professional could be, wonders whether Rooney and Suarez are not forgetting something significant. “I think it’s also nice to be liked and sometimes you’ve got to take that into consideration. How will people look at me or think of me when my career’s finished?” he reflects. That no longer appears to be a consideration. Which only goes to show why football needs to summon some self-respect and begin a little self-preservation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks