James Lawton: Fabregas, Van der Vaart and Modric – the proof that English clubs have failed young players

Did you hear the one about the Dutchman, the Spaniard, the Croat and, this is where it gets a bit far-fetched, the Englishman? The relevance, after Wednesday night's humiliation of a "young" England team by a hardly ancient French side at Wembley, is that two of them played in top-flight football at the age of 16 and the other two at 17.

This no doubt has much to do with the fact that at least three of them, and hopefully four if Arsenal's Jack Wilshere passes a fitness test, will be at the creative heart of the Premier League's most eye-catching game between Arsenal and Tottenham at the Emirates today.

All of them have enjoyed superb educations in aspects of football which remain shockingly remote to most young English pros, including those who happen to have beaten the numbers game and enjoy Premier League action in the hope, we are told so often, that the skills of foreign stars will by some magical process attach themselves to lads like Jordan Henderson.

This splendidly committed and not ungifted 20-year-old Sunderland player this week spent most of his international debut looking for someone to give him an avuncular nudge in the right direction.

The vital process started for Tottenham's brilliant signing Rafael van der Vaart and the exquisite craftsman Luka Modric when they were 10-year-olds signed, respectively, by the academies of Ajax of Amsterdam and Dynamo Zagreb. Both were playing for the first teams soon after their 17th birthdays.

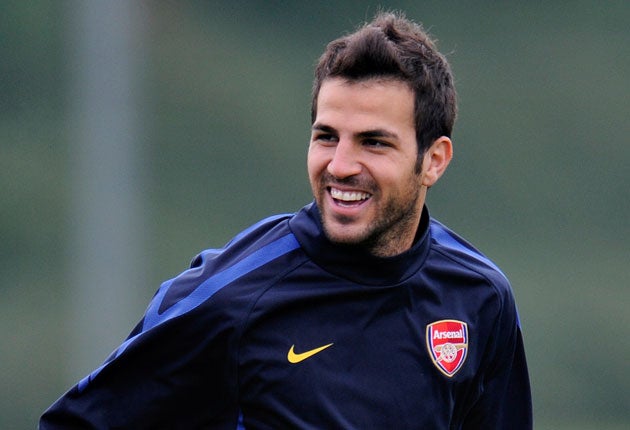

Cesc Fabregas and Wilshere made it through to Arsenal's first team at an even faster rate, with first team debuts as 16-year-olds.

Fabregas's progress has been particularly dazzling with his huge influence at Arsenal and the fact that he already has European Championship and World Cup-winners' medals at the age of 23.

Here, though, is be found the ultimate rebuke to English football and its overall failure to develop so much of its best talent properly.

When Fabregas was approaching his 16th birthday he looked into his future at Barcelona, whose academy he had entered at the age of 10, and saw a series of insuperable obstacles to his chance of quickly striding on to the Nou Camp stage. They included his boyhood hero and now coach of Barcelona, Pep Guardiola, and the pocket giants Andres Iniesta and Xavi Hernandez. So, naturally, Fabregas fled to London and found an almost immediate opening: the chance to replace one of the foundations of Arsenal glory, the Frenchman Patrick Vieira.

If you are wondering, yes, Vieira also made an early start, after arriving in France with his parents as an eight-year-old from Senegal. He played for Cannes at the age of 17 before taking over as captain two years later. When Arsène Wenger agreed to become manager of Arsenal one pre-condition was that he could pluck the 20-year-old out of Milan reserves at the larcenous price of £3.5m.

It all means, at the least the theory goes here, we can watch events at the Emirates on several different levels. We can admire once more the beauty of Wenger's football and at the same time recognise the old pro skills of Harry Redknapp in assembling such an attractive Spurs team on a relatively modest budget (Van der Vaart, the Premier League's player of last month, cost £8m). We can anticipate some powerful surges from Gareth Bale and, possibly, an instant restatement of Jermain Defoe's superior finishing touch.

Most compelling, though, is surely the message carried by Fabregas and Wilshere of Arsenal and Van der Vaart and Modric of Spurs almost every time they touch the ball. It is that there is another game out there, one which the Premier League, for all its resources and self-belief, is simply failing to nurture adequately.

Of course, there are some bright spots and it would be negligent to overlook the thrust of so much of Sir Alex Ferguson's work at Old Trafford, where a superb template was cut by his overhaul of the club's scouting system and the emergence of such as Scholes, Giggs, Beckham and the Neville boys in the Nineties. David Moyes at Everton has also made the development of young players a priority which has had one notable success in the development of Jack Rodwell. Aston Villa have also, for the moment at least, made a commitment to youth.

But these, we have to acknowledge, are the exceptions to a depressing rule. The Premier League has big money and a big appetite but very little of it is for home cooking.

Wilshere is rare in that he is a young Englishman who has time on the ball and a football intellect not likely to be overwhelmed by the quality of a Fabregas; he can keep up with the most biting of on-field conversation.

For Redknapp the big hope today must be that Van der Vaart and Modric can do what they did so well to European champions Internazionale on the night Bale made his great career statement. They undermined Inter with football of the highest creativity, Modric making a goal with sublime originality and the Dutchman scoring it with the easy gypsy-boy swagger that so impressed such as Johan Cruyff and Rudi Krol when he burst off the streets and into the Ajax academy.

Van der Vaart and Modric are exciting examples of footballers whose passion for the game, born not in the easiest of circumstances, has been consistently cultivated. Modric's game was his great distraction from the horrors of the civil wars in the Balkans, which made refugees of his family and cost the life of his grandfather. Van der Vaart is droll about his boyhood in a caravan park. He says, "My father was born in a caravan. It was not a normal lifestyle but I liked it. I always played football on the street. It was an easy life – and then I was 10 years old and went to Ajax."

There he was taught to play the football of the Cruyffs and the Krols and Bergkamps. There his destiny as a fine footballer was made safe, along with another reason why English football should really take a rather late look at itself.

In defence of Tyson the fighter

The other day a word was said here on behalf of Mike Tyson. It was in the context of the shameful Haye-Harrison fiasco last weekend, but now maybe another one is required.

It is in response to the entirely legitimate claim that Tyson, despite his ferocious demeanour, was also involved in some fights which duped the public.

This point was accompanied by the view that I could not have attended Tyson's last fight, when he stayed on his stool at the end of the sixth round against the hopeless Irishman Kevin McBride in Washington DC in 2005.

In fact, I was – and also in Las Vegas 10 years earlier when Tyson, just out of prison, earned something in the region of £30m for dispatching Peter McNeeley, a bar-room brawler from Boston whose trainer entered the ring in the first round to stop a gut-churning mismatch.

In Washington Tyson was 39 and all fought out. He threw everything he had left at the lumbering McBride, and it simply wasn't enough. With Muhammad Ali in attendance, Tyson quit that night, said that his heart was no longer in the ring. He was exhausted.

What one should have said earlier was that Tyson, however dishonest the manipulations of his people, including Don King, was prepared to face anyone and always behaved like a fighter in the ring. That distinction was not properly made.

Truth matters more than the bid

It needs to be said yet again that if the price for staging the 2018 World Cup is some wretched apology for the reporting of corruption in the Fifa process we should consign the ambition to the rubbish dump.

What, exactly, do the organisers of England's bid want? Presumably, it is a curtain of silence until the moment of national rejoicing when the vote comes in. In other words, give us sport's circus and we will do all we can to bury the truth.

The instinct here is that all the junketing and the glad-handing and the politicking and the vast and speculative expense might be profitably dumped in favour of making the quality of home-grown English football something in which we might take pride.

In 1966 we hosted the World Cup, something which somewhat pales against the fact that we also won it. Surely it is obvious which achievement was the more authentic matter for national celebration.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments