James Lawton: Not in the right frame of mind? Refusal to play is more proof of game's detachment from reality

It is especially sad that Pienaar, who was a most impressive figure during the World Cup, is now in the club founded by Lescott and Mascherano

Just imagine you have been in the job for more than three years, one hugely better rewarded than those of the Prime Minister or a field commander in Afghanistan or a neurological surgeon.

Also bear in mind your employer has honoured every letter of your contract right up to this point where you have been offered a new job on even better terms, the kind indeed which would leave most other citizens believing they had been fast-tracked to heaven.

But now there is the question of what you do while considering your situation.

Do you tell your boss that the new prospect makes it utterly impossible to continue operating as a fully paid-up employee until the matter is resolved?

Just about unthinkable behaviour, is it not? But this apparently is not only true in real life; in the bizarre, insuperably self-indulgent world of Premier League football, it is fast becoming commonplace.

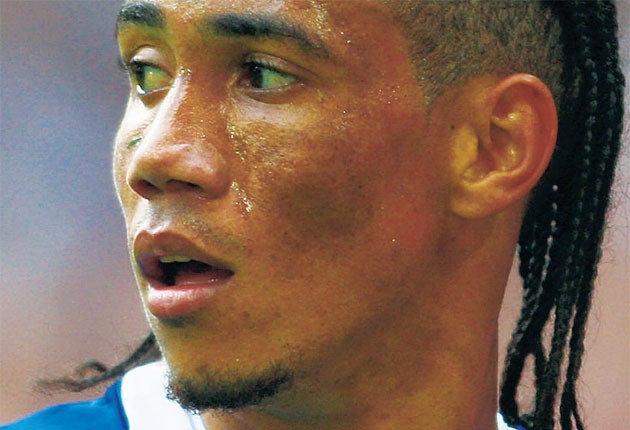

The latest multi-millionaire player to say his head is in the wrong place to fulfil his contractual obligations is Everton's erstwhile crowd hero, the departing Steven Pienaar, who let the news slip to his boss David Moyes shortly before the manager had to pick his side for Sunday's derby game at Anfield.

Not so long ago Moyes might have put on one of his vintage displays of indignation. Given a solid enough reason, Moyes does this better than almost anyone.

An amiable, rewardingly intelligent football man, he does have a very clear idea of the demarcation line between decent behaviour and the utterly outrageous and is rarely reluctant to point it out.

Yet Moyes might have been reporting a mere groin strain when he explained Pienaar's absence from arguably the most important game of the club's season. You see, he threw in the aside, he had been through this before.

It happened to him when Joleon Lescott became so excited about the idea of joining Manchester City he just couldn't consider pulling on the dark blue shirt of the Toffeemen one more time. Moyes was indignant then, all right. He railed against a breakdown in professional values.

He was aggrieved not so much by Lescott's desire for upward mobility, and a much larger income, but his protestation that he was unable to fulfil, however briefly, his professional duty to a coach and a club who had helped to so dramatically transform his career prospects.

Moyes might have also reflected on the fact that he wasn't asking Lescott to perform some tricky brain operation or dismantle a bomb in a Baghdad backstreet but play a game of football in exchange for roughly the deposit on a new house which the vast majority of the nation might consider luxurious.

Now it appears Lescott has his regrets about the move to City – if not the manner of his departure. This certainly seemed to be the case recently when he was expressing anxiety about his future as an England international in view of the fact that he is now roughly a mile behind Kolo Touré and Vincent Kompany in the queue for a place in central defence.

For some of us, though, it is especially disappointing that Pienaar is now in the club founded by Lescott, and joined by Liverpool's Javier Mascherano when he explained to his then manager Roy Hodgson – ironically on the eve of a game at City – that with a move to Barcelona in the making he just couldn't face the humdrum requirements of another Premier League game, however important it might be to Liverpool, his coach, his fellow players and the thousands who travelled to the game.

The South African was a most impressive figure in the World Cup of his homeland last summer and the watching Moyes was quick to express his pride and his admiration. Pienaar was the most consistently effective performer of Bafana Bafana and he spoke well of his emotions as he fought to keep the team in the tournament.

"We want to make these few weeks memorable for our people," he said. "They love football and we want to make them proud."

Pienaar was already a superb example to many of his poorest young compatriots. A product of a Johannesburg township, whose close boyhood friend was a victim of random gunshots, Pienaar went to the Ajax academy in Cape Town, then moved to the parent club in Amsterdam and a stint with Borussia Dortmund before arriving at Goodison Park.

Soon enough he was voted player of the season. He had skill and craft and a fine professional instinct.

These were impressive achievements, especially when set against the fact that the history of township graduates in big-time European football is, to say the least, uneven.

Lucas Radebe, the great centre-back of Leeds United and South Africa who was told "you are my hero" by Nelson Mandela no less, proved that the adventure could be accomplished quite gloriously. But for every Radebe, and Pienaar, a dozen brilliantly gifted youngsters are claimed back by the anarchy of their youth.

This has hardly happened to Pienaar, who was at his most eloquent during the World Cup when he spoke memorably of the meaning of the anniversary of the Soweto uprising which came on the day of a vital game for South Africa. The words were impressive but then so were the deeds. Pienaar played calmly but with bite under the huge pressure of games in his home town of Johannesburg and in Pretoria.

Now a football man of the knowledge of Carlo Ancelotti sees him as a valuable asset in Chelsea's fight to return to the title race. This might indeed represent a fine concluding chapter in a professional career landed against formidable odds.

No doubt the possibility created for Steven Pienaar quite a lot to think about. But enough to stop playing, enough to put aside all obligations except those you think you owe yourself? Yes, we are told. There may be bigger issues in football right now, but can any of them be quite so revealing? Not, you have to suspect, at the average workbench.

Watson rises from ashes to revive Australian hopes

You would have to be a particularly mean-spirited, Ashes-winning Englishman to begrudge for a second Shane Watson the glory he found in the MCG on Sunday.

Watson took the Test match demolition of Australia maybe harder than any of his team-mates. The brawny Queenslander was moved near to tears when he tried to explain the depth of his disappointment to an English interrogator, in the wake of the defeat in Melbourne, which he softened at least to some extent with one of the great 50-over batting performances.

Watson was showered in faint praise during the Ashes. He was mocked for his error-prone running between the wickets – and also for his inability to translate good starts at the batting crease into the kind of run-hoarding that made Alastair Cook the man of the series.

He was also charged with being something of an automaton, a man who could only hit the ball in the direction of mid-off and mid-on with any degree of certainty. If he was in some ways the best of the Aussies, he was also the greatest symbol of their decline.

Maybe, maybe not, only time will tell as the Australians attempt to remake themselves as a serious force in Test cricket with Watson one of their key hopes.

In the meantime, however, the Aussies will have greater faith in their ability to win another World Cup. For this vital boost in morale, Shane Watson is due the warmest credit. He was arguably the most impressive, blood-charging automaton in the history of cricket.

Lofthouse the reluctant hero remains the deadliest of England sharpshooters

It may be impossible to believe now, but there was a time when Nat Lofthouse, the Lion of Vienna, was not the admirable yeoman footballer mourned at the weekend but a figure of impossible glamour.

His potency on the field was electric. He never did anything without a hard and brilliant purpose. He ran, he scored and with the self-effacement of the times he returned to the centre circle with a brief wave of his hand and the hardest intent to resume the assault.

There was, with the possible exception of Sir Tom Finney and Sir Bobby Charlton, never a more reluctant celebrity.

Imagine what we would make of a player today who scored 30 goals in 33 internationals. Alan Shearer played 30 more games for the same total, Michael Owen had 56 more caps for 10 more goals, and arguably the greatest finisher of them all, Jimmy Greaves, surpassed Lofthouse's total by a mere 14 goals in 24 more matches.

Apologies for going on but here Lofthouse was the first hero, pure and unadulterated, and even more so than Matt Dillon, marshal of Dodge City.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments