James Lawton: The truth behind the phoney war

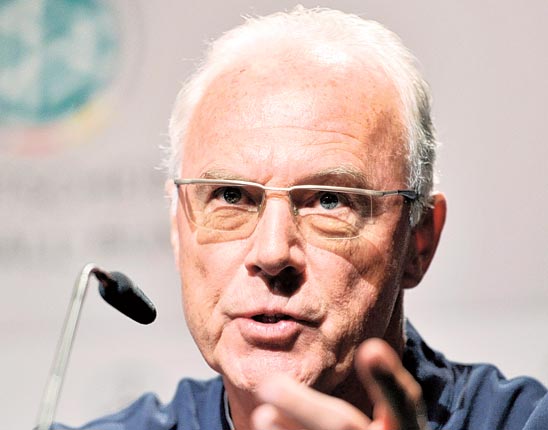

Beckenbauer’s negative soundbites about England are intended to provoke - but is he right? Our writer looks back to 1966 to get under the skin of Germany and Der Kaiser

So now, naturally, the Kaiser appoints himself Minister of Propaganda. It is time to run another lance through the stirrings of English revival before Sunday's round of 16 in Bloemfontein, an occasion to turn the screw at least once more.

This is entirely appropriate because you could scour the world without finding a judge better qualified than Franz Beckenbauer to identify the chasm that yawns so wide between the international pedigree of his nation and the one Fabio Capello is attempting to hold together with what at times has seemed like so many strips of sticking plaster.

Stupid, burnt-out, regressive are a few of the insults directed at England by Beckenbauer from the pages of the Bild newspaper.

They hurt, let's be honest, so much because their source carries such authority – and also because we suspect they may be true.

Long ago German football's ability to remake itself in the most unpromising circumstances became a self-fulfilling prophecy and there has been more than a touch of agony here, as England explore their shocking depths, watching the latest manifestation.

Indeed, Beckenbauer's most worrying charge – that the demands of the Premier League and two national cup competitions have left England looking jaded and morose compared to the freshness of a new German side – came vividly to life when his compatriots played their way into the path of England.

The goal that did it flowed from the sweetest of strikes by 21-year-old Mesut Ozil. The third generation son of Turkish immigrants, Ozil looks as though he is involved in the greatest adventure of his life. His older, English contemporaries might be fighting through their biggest ordeal.

There is a special pain in this because Beckenbauer knows better than anyone that no two football nations are as close, physically and psychologically, as Germany and England. The difference is sustained performance and a clear understanding of what can be achieved with certain attributes, most notably strength and a degree of moral courage.

German football strengthens itself and compensates at the weakest places. English football tends to do the opposite.

The great Dutchman Johan Cruyff once spoke of the enduring mystique of the English game – and the ability of its players to inflict a little doubt, an element of fear in any opponent. He said it was one of the most consistently wasted assets in football. It was a renewable resource that just kept draining away. It was a tragedy understood least by the English.

"No one, not even the Germans, can take anything for granted against the English footballer," said Cruyff, "because we know for sure certain things about him. He is strong, he is brave and he will never accept that he is beaten. European players may have better technical skills but every coach is envious of English heart."

This is the quality Beckenbauer has acknowledged even in his latest broadside, saying "You cannot dismiss the English and I still believe that if Rooney can catch a little on fire they will be a threat to anyone."

But then this quality of English fortitude has become strained here in South Africa and for Capello the hope has to be that the sharply improved showing against Slovenia represents something more than a mere prolonging of a World Cup trauma.

For this reason the drawing of Germany could hardly be more savage in its potential implications. The disturbing truth, as England attempt to raise their game by at least one vitally necessary notch, is that no team has ever shown a more brilliant facility than Germany in the matter of overachievement.

It is the most stunning story of consistency, of sheer obdurate refusal to concede superiority in any opponent, that Germany seek to expand into still another chapter on Sunday. Given the delicate state of England's self-confidence, it threatens to be not so much a challenge as a judgement.

It is a test, certainly, that means England must match the German genius for making the best of their resources, however modest they are.

Germany has done it so many times that the English football brain must ache with the memory. Only Germany, surely, could have conjured the will to stop the march of one of the greatest teams in football history, Hungary, in the World Cup final in Switzerland in 1954 – the Hungary which had ravaged England 6-3 at Wembley and 7-1 in Budapest in the preceding year.

Only Germany could have wrung out the drama so deeply in England's sole World Cup triumph at home in 1966. Only Germany, with Beckenbauer nursing an arm in a sling, could have avenged that defeat in the excruciating heat of Leon four years later, when England's coach, Sir Alf Ramsey, was so confident of victory he withdrew a Bobby Charlton who was operating as a master puppeteer, pulling one string after another.

You could grow old using the phrase "only Germany" because the record never ceases to stun when you go back over the unique details and the extraordinary circumstances: seven World Cup finals, three victories, and more than half of their appearances achieved against the heaviest of odds.

In 1974 they watched the superb Dutch team of Cruyff overrun them in the Munich final, then fought back to win under the majestic leadership of Beckenbauer. In 1982 their best player and captain, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, was crippled but he still led them to the final in Madrid.

It was the same in Mexico four years later, when Argentina, despite the surreal brilliance of Diego Maradona, could only carry the final by the margin of one virtuoso moment from the man of the tournament.

They won in Rome four years later. Beckenbauer was the coach eking out bare levels of talent, but they beat Maradona's Argentina and confirmed their status as the team who didn't understand the concept of defeat. Of course, by way of formality, they had beaten England on penalties in the semi-final in Turin.

If England's captain on Sunday, Steven Gerrard, machetes his way back through to the night in Munich when, as a 21-year-old, he played a significant part in an astonishing 5-1 victory, he is also obliged to recall what happened less than 12 months later in Yokohama. As England nursed their wounds at home after quarter-final defeat by Brazil, they watched Germany appear in their seventh World Cup final.

This is the weight England carry to Bloemfontein and shedding it is plainly the great challenge now facing Gerrard's ageing generation.

Can they do it? Everything depends on Capello's ability to recreate the confidence that seemed so secure when he took hold of the qualifying campaign, when it seemed that he, like Cruyff all those years ago, had recognised the strength of the English footballer and had done so much, so quickly, to separate him from his doubts.

Here these last few weeks it has been painful to see Capello's need to go back over all the old ground, so basically, that it has not been totally reassuring to hear him insist this week that the "spirit is back". Maybe it is, maybe isn't. The only certainty, of course, is that for Germany it remains an asset that does not come and does not go. It just keeps coursing through the blood.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks