It is easy to laugh at Joey Barton for speaking to the Oxford Union or tackling a philosophy degree, but his courage actually deserves praise

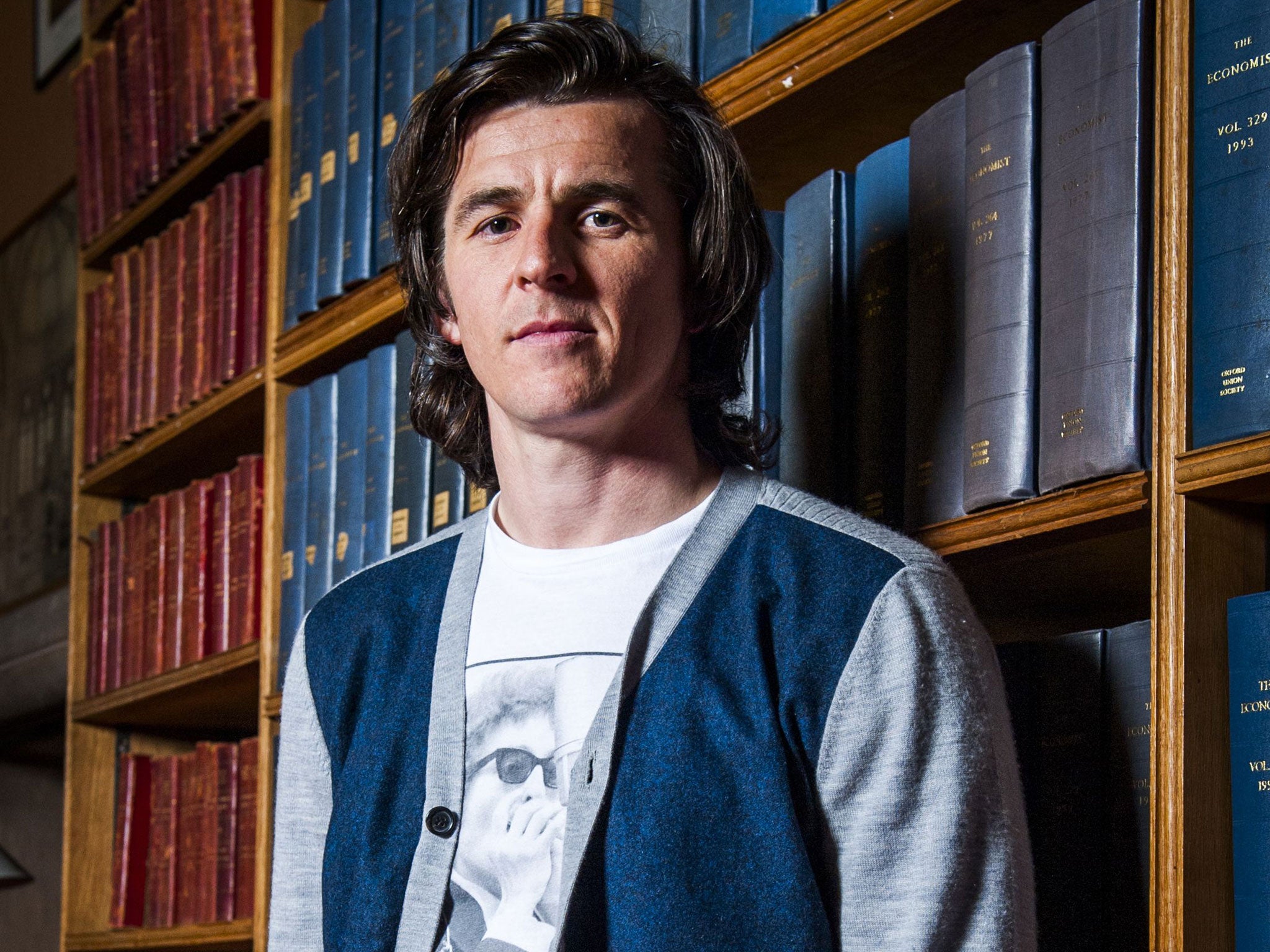

Here Barton is with his head in a book rather than at the bookies, writes Kevin Garside

It has been a busy week for Joey Barton: an address at the Oxford Union followed the next day by a haircut. If his appearance before the brilliant young things last Wednesday was a leap, the shearing was no less so since it reversed the cultural order of things. When Barton was a lad he would have had the tidy-up before the big engagement.

Barton is an easy target for the sneering tendency, dismissed as a reformed oik, a self-styled spokesman for the football intelligentsia, purveyor of the faux French accent, dispenser of Twitter wisdom via the philosophical quote.

There is a keen mistrust of those who wear their born-again status so visibly. Who does he think he is? Trying to be something he is not, etc. Barton is anchored to a past littered with boorish indiscretion. Dispute resolution was typically violent, the legacy on his upbringing in the working-class hard lands of Huyton.

I prefer this version than the one that stubs fags out on the eyelids of team-mates. Barton is still attached to elements of his old identity and class reference points, but that is not surprising. The direction he has chosen meets opposition from above and below. You can imagine how the Oxford experience was received in L36, arguably with less enthusiasm than it was at Debrett’s.

Barton is one of a cluster of notable footballers from the neighbourhood, including Steven Gerrard. Not sure it has produced too many cabinet ministers, however. That would require entry to Eton, of course, and that was never going to happen.

The grammar school system, or faith schools (Alan Bleasdale), was historically the route out of poverty for the downtrodden. Even that was a long shot for kids from the kind of troubled background from which Barton emerged. In the modern era sport provides that leg-up, coming to the rescue of working-class lads like Barton, for whom a spell in the school library was received like a prison sentence.

These days you can barely keep him out of one. His enrolment at university to study for a philosophy degree is a remarkable step, and potentially his greatest service to the game, for it reinforces the value of learning to a social group dismissive of it.

It cannot have been easy for Barton to present himself for questioning before students at one of the world’s great universities. It will have prodded at insecurities masked on the pitch. Imagine if Barton were to have thrown a QPR shirt at a student and invited him to line up against Yeovil last Saturday. A football blue is nil preparation for the professional game yet that is the kind of equivalence we are talking about.

It is time to pay our respects to Barton, to acknowledge the courage required to substantiate a life that hitherto conformed to the worst of football’s excesses. The passing of Sir Tom Finney drew a line under the immediate post-war epoch when deference was imposed via the minimum wage. Sport’s migration to mass entertainment in the smart phone age enriches even modest talent in a way Finney’s generation could not have dreamt.

This wealth is appropriated largely in the manner of the Lottery winner, effecting an immediate upgrade in house, car and holiday. Barton threw himself into that lifestyle with some gusto. And why wouldn’t you?

Typically, footballers rarely find the keys to an enlightened life. Some even manage to blow the advantages instant wealth confers, on gambling, drinking and so on, reaching a dissolute dead end, the kind of finale to which you imagined Barton might have been heading.

Yet here he is spending his afternoons with his head in a book rather than at the bookies. That has to be cause for celebration, and deserves the wider recognition that social media provides. Barton was quickly on to Twitter pointing his 2.4 million followers, of which I am one, to the highlights reel from his Oxford debut.

After a nervous start he grew into the environment, working out that his life experiences were of unique value in this setting and conferred a kind of understanding of the world that those sat before him just did not have. This is the kind of example disenfranchised kids need. Barton was not turning his back on his past, rather bringing it to bear in a new, enlightened milieu.

There is a poignant parallel in history. The last effects of Tommy Taylor, who lost his life in the Munich tragedy, revealed two self-help books. Taylor was the centre-forward for Manchester United and England, a player of huge standing having scored 112 goals in 168 league games for the red shirt, yet it appears he was searching for a way to greater fulfilment.

It was Taylor’s sister-in-law, gathering up his worldly goods from his digs in Manchester, who made the discovery. “We found two little black-and-yellow books. One was Teach Yourself Public Speaking, the other was Teach Yourself Maths. It broke my heart when I saw those. They showed just how much he wanted to improve himself.”

No one ridiculed Taylor in death, neither should they Barton for new life choices.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments