Sam Wallace: England needs to tap into diverse communities – not tap up Ilori

England once led the way with the sons of Caribbean immigrants

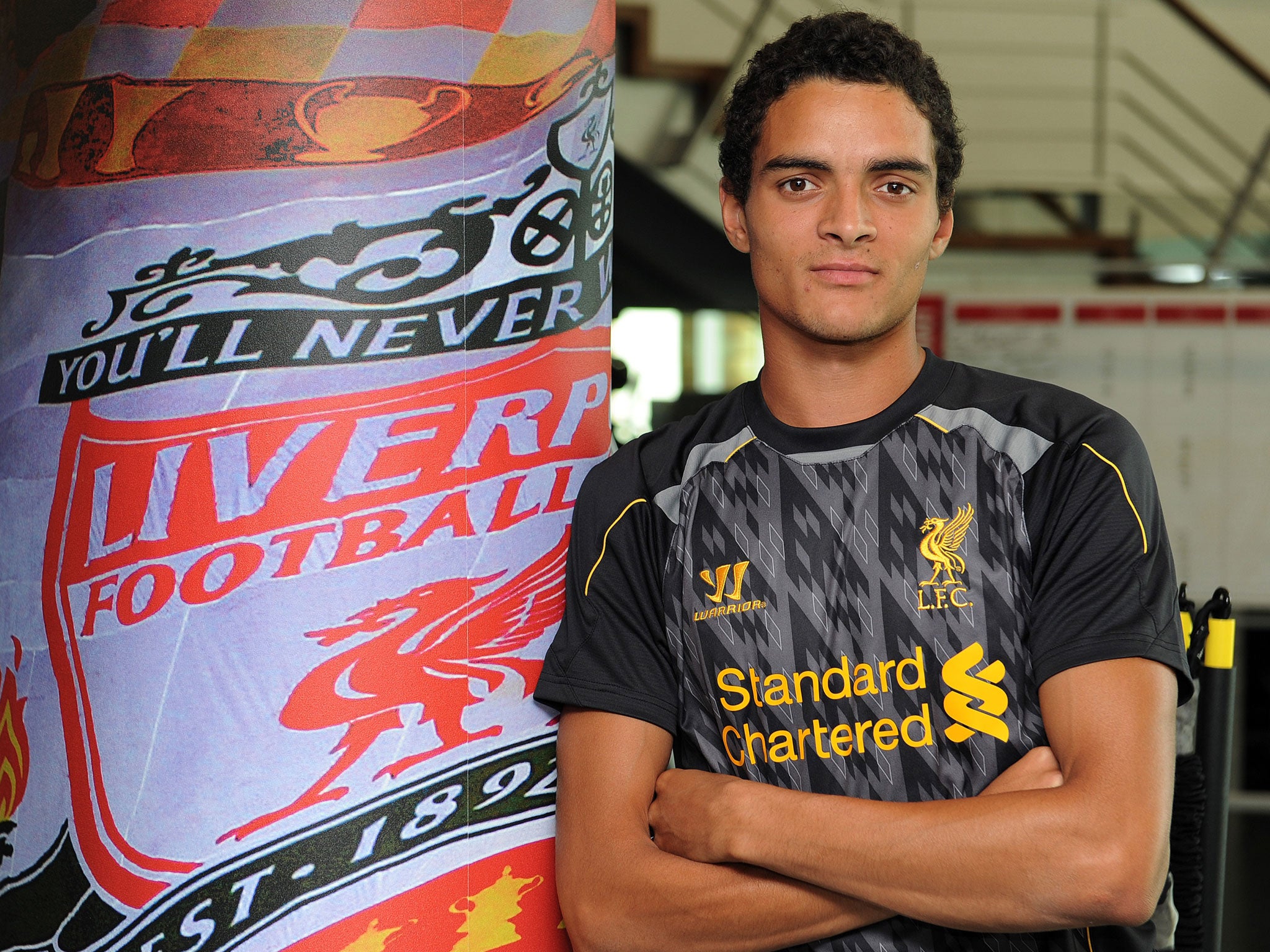

Should the Football Association wish to pursue its interest in persuading Tiago Ilori, Liverpool’s new £7m, London-born centre-half, to represent England at senior level it may wish first to consult a pertinent feature on the player on his new club’s website.

Ilori, 20, signed from Sporting Lisbon, “can speak fluent English” according to liverpoolfc.com but “considers himself Portuguese”. Not surprising, really, given that he moved to Portugal at a young age and has played for the country at three junior levels. His father is Nigerian, his mother Portuguese and there is no doubt an interesting modern-European back story to be told, but let’s face facts here: he’s Portuguese.

It is almost three years now since there was a brief spell of excitement about the possibility of the then-Germany Under-21 captain Lewis Holtby playing for England. It was a personal view at the time that the FA should have done more to persuade Holtby, who had an English father, to play for England. He sounded English. He was part of a great generation of German footballers. It seemed too good to be true.

On reflection it was pointless to pursue Holtby (even if he cannot get in the Germany squad these days). He might have a name like a solicitor in a well-to-do provincial English town, but he is, well, German. He had played at three junior levels – Under-19s, Under-20s and Under-21s – for Germany. He had been born in West Germany 15 days before it was officially re-unified with the east. All his football education had been there. He was English by a technicality; German by nature.

Equally, chasing after Ilori is starting to feel a bit desperate. He is Portuguese, just as his erstwhile Sporting Lisbon team-mate Eric Dier considers himself English. An England Under-21, Dier was born in Cheltenham but moved to Portugal at 10 when his mother got a job working on the Euro 2004 tournament.

Only 19, Dier has played for England at Under-18s, Under-19s, Under-20s and Under-21s. One would imagine that the Portuguese football federation has got the message and is no longer pursuing him. His grandfather is the late Ted Croker, a former secretary of the FA. You do not get much more English than being a descendant of an eminent FA blazer.

It is a funny thing, nationality. It can only be divined by the individual because it is about a sense of belonging. In fact in certain lives it can have very little to do with where, geographically, one is born. And if you do not believe that, it is worth considering that Terry Butcher, he of the bloodied shirt, was born in Singapore.

Saido Berahino scored the only goal in England Under-21s’ win over Moldova on Thursday, fresh from his debut hat-trick for West Bromwich Albion against Newport in the Capital One Cup. Berahino’s story is well-known, his family having sought political asylum in the UK from Burundi. Wilfried Zaha (Ivory Coast) trod a similar path while Raheem Sterling (Jamaica) is another recently capped player born outside England.

Even so, there is the nagging feeling that English football has some catching up to do in this regard. Naturally, the patterns of immigration into any two countries will never be the same, yet it feels like English football – once the most diverse domestic game in Europe – is behind other big EU countries.

One can hardly overlook Germany’s modern generation that includes Mesut Ozil (the third-generation descendant of Turkish immigrants), Sami Khedira (Tunisian father), Mario Gomez (Spanish father) and Sidney Sam (who previously had eligibility to play for Nigeria). Not to mention Polish-born Miroslav Klose, whose goal against Austria on Friday took him level with Germany’s all-time record international goalscorer, Gerd Müller, on 68.

Equally, there appears a much richer diversity of backgrounds in France’s current squad. This is the nation that won the 1998 World Cup with the Senegal-born Patrick Vieira and Ghana-born Marcel Desailly and two years later won Euro 2000 with a goal from David Trezeguet (French born, but having grown up in Buenos Aires).

When English football focuses on its future, as it was forced to do last week by the FA chairman, Greg Dyke, it would do well to ask itself how it can develop a generation of boys whose families have moved to the UK in recent years into future internationals. Certainly when one considers the names of many current academy squads, that generation should be about to mature as professionals.

There will always be cases like that of Victor Moses, who came to the UK from Nigeria as an asylum seeker, who, having played for England at junior level, chose to play at senior international level for the country in which he was born. That has to be respected, and yet it would not reflect well on English football and the England team were it to become a trend.

A modern, enlightened European football nation should have its diversity reflected in its national team. It is a strength to draw upon, as Germany have shown in recent years. Football clubs have a good habit of going into the kind of inner-city communities that can often become isolated in search of talented footballers. They do it for their own ends but it is undoubtedly a mutually beneficial arrangement.

The FA officials who have got to know north-west London since their move to Wembley as the organisation’s headquarters will have noticed that the area encompasses a big Brazilian community. If ever there was a good youth development opportunity for English football it is surely the Brazilian-British generation (the Brazbrits?).

Modern England has to play to its strengths. It once led the way when the sons of Caribbean immigrants broke through into professional football in significant numbers in the late 1970s, although we should never pretend that was easy for those involved. Now it is crucial for the 21st-century generation of newcomers to be absorbed into the game for the benefit of all.

In that regard, it already feels like Germany are a long way ahead. Certainly diversity is a tradition of English football that should be upheld. And it is much better than trying to persuade a Portuguese footballer to jump ship simply on the basis of the relative unimportance of where he happened to be born.

Serbia keeps calm in wake of Croatian assault

What was striking about Josip Simunic’s nasty tackle on Serbia’s Miralem Sulejmani on Friday night, for which the Croatian was sent off, was not so much the cynicism of the challenge. Rather it was how relatively calm everyone stayed in the aftermath. This, after all, was Serbia v Croatia. There was a bit of remonstrating and both sides finished a game described as “ill-tempered” with 10 men. But given the context it felt like a grown-up reaction all round.

‘Home-grown’ rule does little to level the field

In the debate over producing English footballers, most people now understand that any quota system would be illegal under European Union law. In fact, Uefa had to get special dispensation from the EU to create the “home-grown” rule in 2005, which in itself doesn’t discriminate along nationality lines. A recent study of the home-grown rule by Liverpool University cast doubt on the value of the sanction, claiming that its effectiveness in improving the competitive nature of football was “modest” at best.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks