The muddy truth of the Christmas Truce game

A new exhibition reveals that tales of an arranged football match during the First World War are not quite as digestible as previously offered

Examine the item at the centre of the National Football Museum’s new exhibition marking the First World War and you will wonder how there could be space for such carefully formed delicacy – an object of beauty – amid the horrors which were beginning to unfold on Christmas Day, 1914.

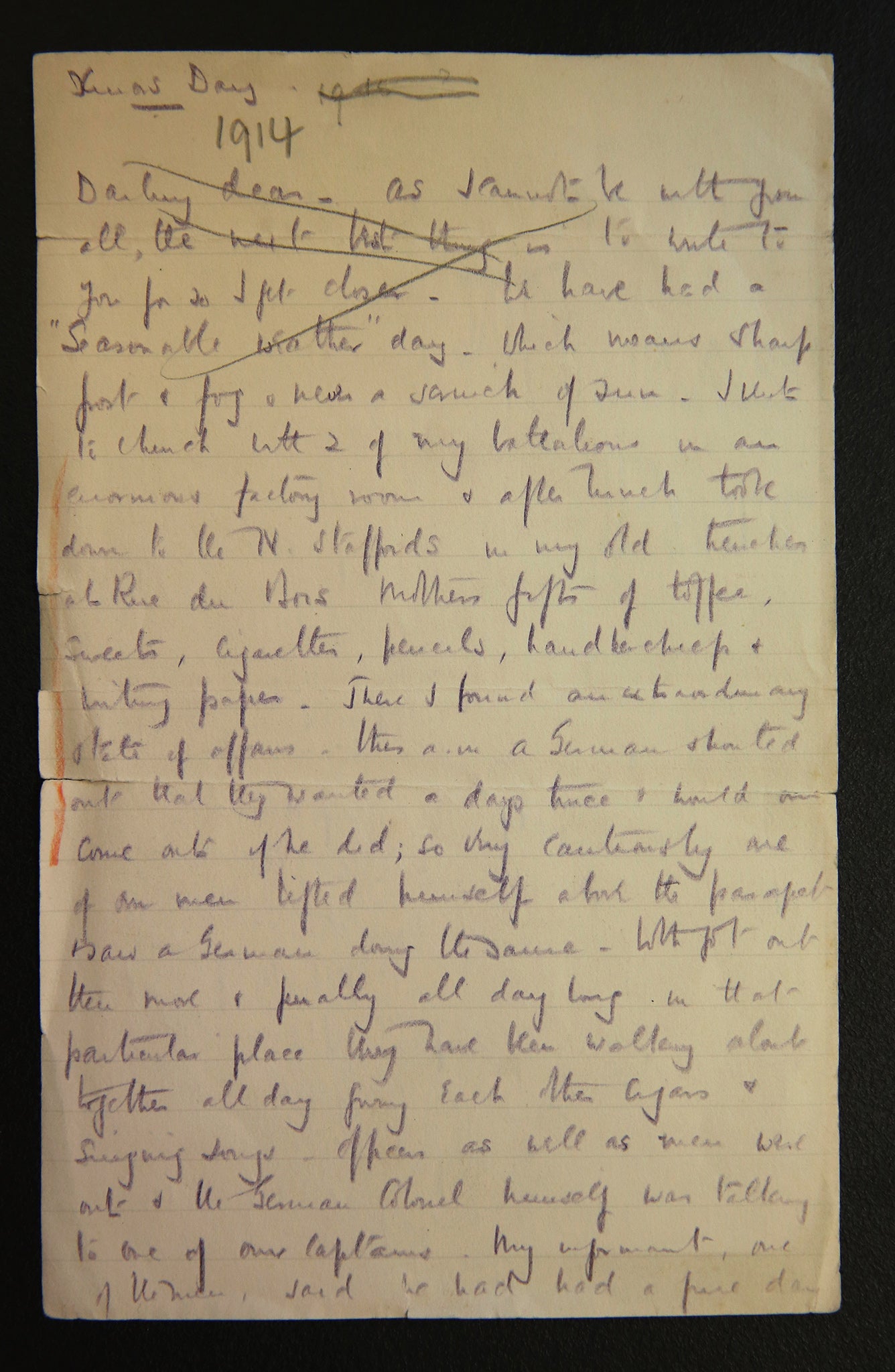

It is the diary of Lieutenant Charles Brockbank; page after page of tiny, immaculately even handwriting in which the Cheshire Regiment soldier laid out his daily testimony in black ink, capable, as he was, of stepping outside the physical agonies which were befalling the 6th Battalion and consigning them to paper. His Christmas Day entry is testament to a night the likes of which we will not experience – “the most agonising I have ever had,” as Brockbank described it, enduring what reads like the onset of frostbite until 4.30am, when even the threat of sniper fire cannot deter him from stamping around in the mist of the frozen dawn.

Then, a momentary release, rounding up hens with his compatriots on a deserted farm behind the lines. And then “the most extraordinary incident”, Brockbank wrote. A cease to the firing at 2.30pm and “the Germans started shouting to us to ‘come out’ and ‘have a drink’ and also climbing about in the trenches. One of them came out in front without rifle or arms, as one of ours went out too. A huge crowd formed... We had found a little rubber ball so, of course a football match came off and we exchanged various things...”

Note the casual description of the object which served as a football because it was not the laced-up pig’s bladder which belongs to the legend of how two sides played out a game of football 100 years ago tomorrow, perpetuated by the film Oh! What a Lovely War, the Sainsbury’s TV advertisement this Christmas and countless others in between. Although up to 15 ad hoc matches took place along the Western Front, the evidence of an organised meeting between the British and Germans in no-man’s-land to play football a century ago is thin – as the new exhibition reinforces.

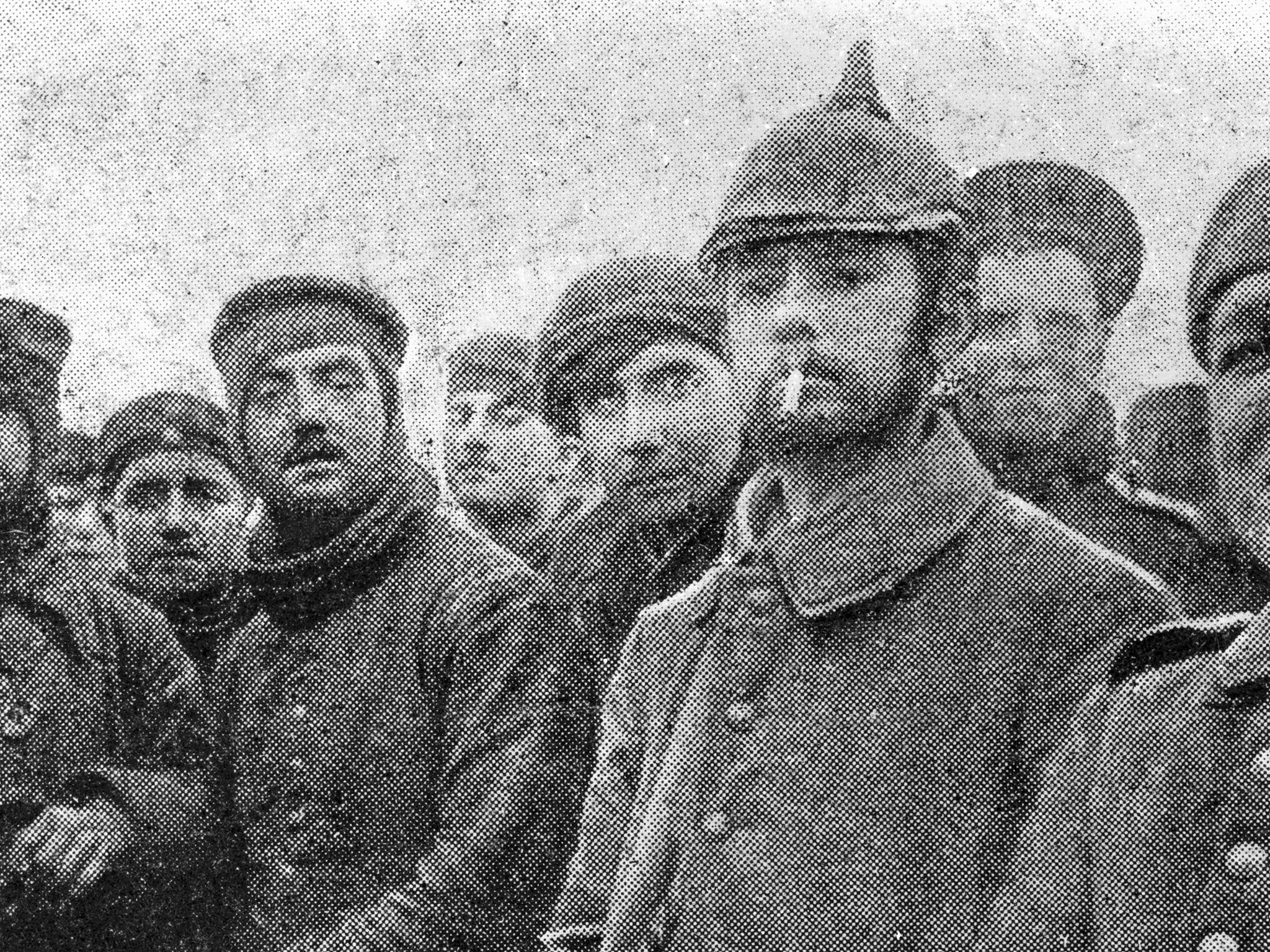

Its artefacts also include one of the best known images of the so-called Truce match – taken, it transpires, 1,500 miles south-east of the trenches at Salonika, in Greece, when the 133rd Royal Saxon Regiment played the Argyll and Sutherlands Highlanders on Christmas Day 1915: a 3-2 win for the Germans. The evidence of an arranged Christmas Truce game is equally slim in the testimony of Private Ernie Williams, who served in the place where the game is thought most likely to have taken place – a turnip field on the vividly named “Stinking Farm” near the village of Messines, on the France/Belgium border where the 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment and the 16th Bavarian reserve infantry regiment laid down arms. Williams talks of the commanding officers – with whom the soldiers did not circulate – ordering the men back when the fraternising started. “One officer was shaking his hand, saying, ‘Oh, bloody fools, you don’t know what you are doing,’” Williams relates. “They thought it was a trap.”

The doubts the exhibition raises bear out the testimony of Lancaster University’s Dr Iain Adams, whose research points to ad hoc truces along 17 miles of British lines, though nothing organised. Neither did they did start with a football and Stille Nacht on Christmas Eve. The Argylls and Highlanders were opposite the 134th Saxon Regiment before Christmas 1914 when a nearby river flooded and with it the trenches, too, forcing both sides to climb out and rebuild, less than the length of a football pitch away from each other. “They didn’t shoot at each other but started sharing tools,” said Adams, whose research featured on the BBC World Service’s Sportshour. “When you are working with people and are face to face, it is quite hard to shoot them.”

Football, never backwards in claiming its part in world events, has never been too concerned about the gap between myth and reality. Uefa has unveiled a memorial to the truce at Ploegsteert, in Belgium and Fifa’s president, Sepp Blatter, gratefully seized the opportunity too, referring in his organisation’s magazine yesterday to how soldiers “laid down their guns and emerged from the trenches to play football”.

But the lesser known, less saccharine story of football and the First World War, tells how the sport was used as part of the propaganda effort to get men out to the front. The Football Association’s hugely controversial decision to continue the 1914-15 season when war broke out placed it under fierce attack from our national press, accused of discouraging fans from joining the troops and instead offering them football to watch.

The Times featured on the cover of the Chelsea match programme of 5 December 1914 – a goalless draw with Sheffield Wednesday – when caricatured as “The Mudslingers” in a cartoon attacking the club. “Come on boys, keep it up, some of it is bound to stick,” read the caption sarcastically.

But the game was soon at the hub of the war effort. The Government publicised a Frankfurter Zeitung editorial – ridiculing British footballers for “exercising their long limbs on the football ground” instead of serving at the front. Some very tired football metaphors were a part of the enticement. “Every man can help in keeping the Teutonic team as far away as possible from our goal area. Forwards are required as well as backs,” the former sportspaper Athletic News proclaimed.

The sport did not take long to respond. This month also marks the centenary of the Footballers’ Battalion, which was formed. The video footage of its members laughing and joking as they limber up for some exercises – as their battalion was used as part of the propaganda encouraging mass conscription – is one of the new exhibition’s most heart-breaking artefacts. Little did those men know what lay ahead of them, that Christmas.

So many fledgling football careers were cut short. There was 26-year-old Jimmy Speirs, a richly gifted Scottish striker who was Bradford City’s captain and goalscorer when they beat Newcastle United 1-0 in the 1911 FA Cup final replay at Old Trafford. Herbert Chapman – manager of Leeds City at the time – bought him for the very substantial sum of £1,400 and he had become an even more prodigious goalscorer – 73 in 32 games – when the call to war came, claiming his life in April 1917.

There was Wilfred Bartrop, whose part in Barnsley reaching the FA Cup final in 1910 and winning it two years later earned him a move to Liverpool. He had played only three games for them before the war came, but his dreams of treading the Anfield turf again were becoming real as the conflict reached its end. He died while providing mortar support on 7 November 1918, just four days before the end of the war, and was the final footballer to lose his life in the conflict. The Christmas Truce is the soft, warm, digestible narrative of an apocalyptic conflict. The story of these men and countless others is its harsh reality.

The Greater Game: Football & The First World War, a free exhibition at the National Football Museum Manchester, until 6 September 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments