Chelsea profits comment: Roman Abramovich learns that stability and cool heads can still win trophies

Blue’s profit shows the Russian has taken account of FFP and is less driven by his emotions

There was a time, barely two years ago, when the bumpy landscape of Chelsea Football Club showed no sign of flattening out. The team had just lost 4-1 in the Super Cup final in Monaco to an Atletico Madrid side for whom Radamel Falcao was unplayable, and owner Roman Abramovich felt the need to take the temperature of the dressing room and observe the response to manager Roberto Di Matteo.

Abramovich is often to be seen in there after a game, shaking players’ hands, engaging in brief conversation before leaving, but on that night in August 2012 he stalked the dressing room for a full half-hour, looking, listening and also taking a seat next to Di Matteo.

It was an excruciating experience for the manager. Abramovich said nothing to him in the five minutes they sat side by side and the Italian could summon no words, either. Three months later Abramovich sacked him and his search for a ninth Chelsea manager in as many years prompted the usual conversation about Abramovich’s autocracy and the club’s endless instability.

The ups and downs of football which that night represented – the chessboard unpredictability of the game and the challenge of seizing control – is why Abramovich likes it so much and is also why he never responds when asked to predict a result. But the club’s arrival in a land of substantial profitability reveals a proprietor who has been willing to play things more simply and strip some of the emotion out.

One aspect of his Russian psyche indicated the advent of Uefa’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) would create more controversy for him and his club. There is an innate Russian inclination to hold on to possessions and not want to sell, which explained why players such as Andrei Shevchenko and Fernando Torres were retained so long by Chelsea when other clubs would have shown them the door.

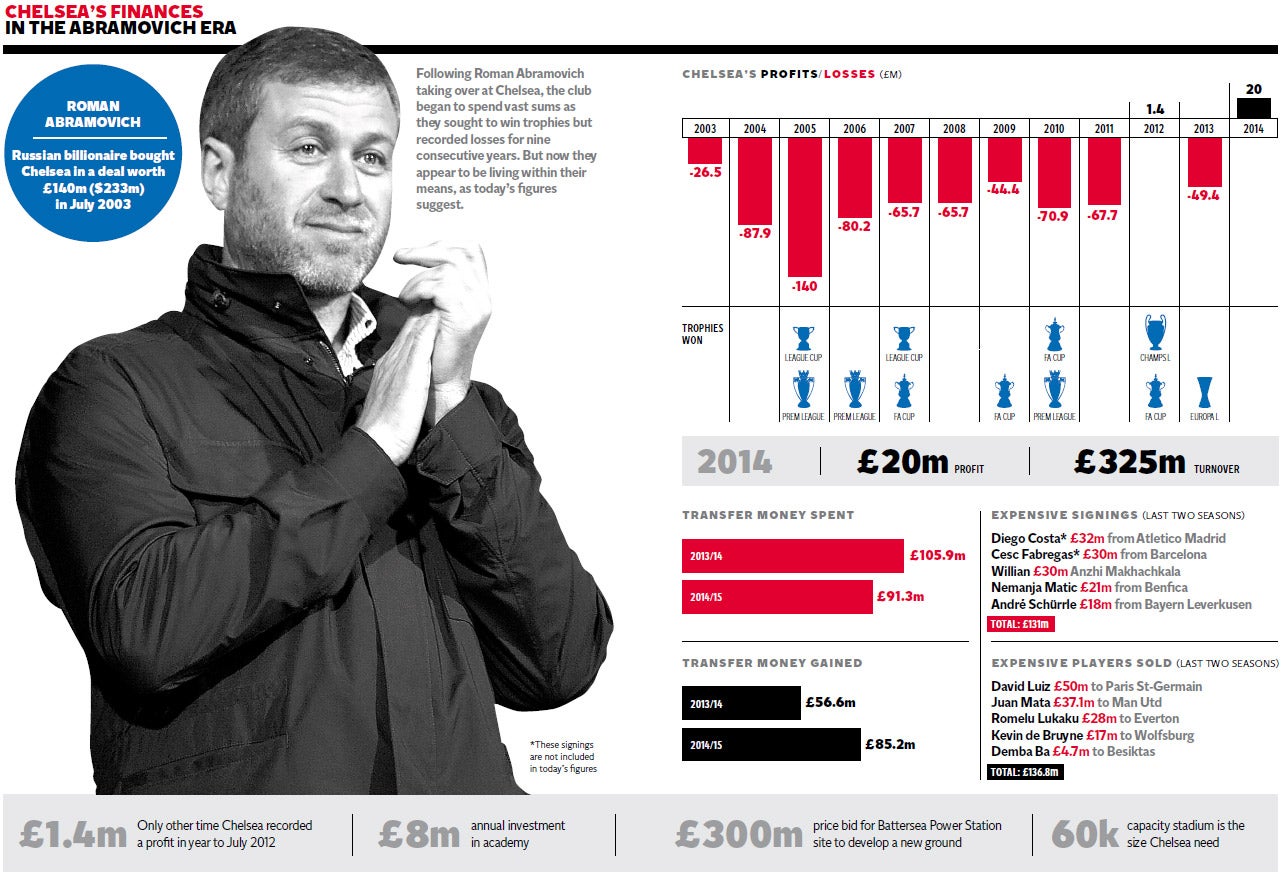

Click HERE to view full-size graphic

But FFP has created the need to let some players leave at least a year earlier than they might have done. Though it would have taken extraordinary possessiveness to reject Paris Saint-Germain’s £50m offer for David Luiz, the defender’s departure in the summer along with that of Juan Mata – earning the club £87.1m – have helped deliver the profit figure.

The purchases of Diego Costa for £32m and Cesc Fabregas for £27m do not feature in the results but a net £28.1m gain for those buys, when set against the Mata and Luiz sales, tells how a profitable Chelsea have managed to command the Premier League this season.

The stability can be traced to the manager’s office. The relationship between Jose Mourinho and Michael Emenalo, the club’s technical director, is substantially better than the one the Portuguese shared with Frank Arnesen during his first spell at the club. The two are said to occupy each other’s offices in a way that Mourinho and Arnesen never did. But the quieter, less fractious Chelsea also has something to do with the new Mourinho we are witnessing, second time around.

Mourinho does not want to be seen as the enemy of football any more, which is why he has been receptive to the suggestion that he should stop picking fights. He is still very adept at twisting the knife in press conferences. Witness the two consecutive digs at Manchester City’s Manuel Pellegrini – or “Pellegrino” as he deliberately misnames him – before the 1-0 win at the Etihad in February. He accepts that the Chilean will never respond but works on an understanding that players in opposition dressing rooms read these comments and expect their own manager to react.

But Mourinho, 10 years older than when he first arrived in London, seems to have been convinced that the usual cycle of negativity – opposition manager (typically Arsène Wenger) says something negative, journalists put it to Mourinho, Mourinho hits back – only fuels public dislike. Mourinho’s declaration in February that Wenger was a “specialist in failure” – in response to Wenger saying that Mourinho possessed a “fear to fail” – was a source of regret.

There is no telling how much of the former spikiness may return when Chelsea reach the business end of the season but we also seem to be observing a Mourinho who is thinking more about his legacy. Those close to him talk of a greater interest in youth players than we used to see, with the £8m outlay each year on the club’s academy creating an expectation that it will help sustain the profit revealed in the figures.

The academy is finally producing players who are in contention – Dominic Solanke, Izzy Brown, Lewis Baker, Jeremie Boga, Patrick Bamford and John Swift, with Nathaniel Chalobah not far off. The frustration is the demands the club are facing from English teenagers with an all-too-great a sense of self-worth. One 18-year-old scholar, sitting alongside his agent, skim-read a contract which Arnesen had just handed him and responded: “This contract is shit.” His Chelsea career was swiftly over.

The contractual hard-bargaining is the terrain of Marina Granovskaia, the long-time head of Abramovich’s family office whose heavy involvement in transfer business dates to the £50m Torres deal in January 2011.

It is said that the unwillingness of agents to dish out to a woman the foul abuse so typical in the unreconstructed world of football has been one of the characteristics of dealings under Granovskaia, who has built a reputation for powers of negotiation and a fierce grasp of financial detail. The departure of Ron Gourlay as chief executive means that Mourinho and Emmenalo report to her on a number of issues.

The days of player power at the club – with John Terry and Frank Lampard having a line into the owner – do appear to be in the past. It was a sign of how much that dynamic had reduced as far back as 2008 that when Terry, Lampard and Petr Cech were in Monaco for the Uefa Team of the Year event they were surprised to receive a call from Abramovich to say he was on his yacht, and asking them to join for a drink. However, a helicopter was scheduled to get the three home, so they were frustrated to miss out on the drinks – especially when the helicopter was delayed.

But there is a very big challenge on the horizon which Chelsea are yet to crack: how to expand a Stamford Bridge stadium which has a 41,798 capacity – a dangerously low figure in the FFP era when strong match-day revenues are needed to help subsidise squad enhancement.

Chelsea were denied the perfect venue for a new stadium – the Battersea Power Station site – when a Malaysian consortium, intent on a London presence, blew their £300m bid for the land out of the water with an offer of more than £400m. Local authorities have drawn the club’s attention to Old Oak Common, where Queen’s Park Rangers are now planning a new ground, and the Olympic Stadium.

But the club are intent on staying at Stamford Bridge and developing it, despite obstacles which mean that the project would take five years to complete, if the first spade was in the ground tomorrow, with two years needed just on the planning. Though a one-year ground share at Twickenham is under consideration, they harbour no desire to attempt to make the rugby union arena an 80,000-capacity permanent home.

Chelsea would admit that overhauling the Bridge does not make conventional business sense, with a listed building and a cemetery amid the impediments, though the level of the water table is not quite such a problem as had been thought. The cost of the overhaul will be £20,000 for every new seat they put in, yet the arguments in favour include the clear financial advantage that Chelsea are currently handing Arsenal.

The north London club earn £2m more per match and £35m more per season in match-day revenues than their rivals to the west. The fact that investment in infrastructure does not form part of the FFP calculation is significant, too. It means Abramovich may spend what he wants.

Someone who has known the club’s journey through the “upstart” period of the Abramovich era to these relatively calm waters recently reflected that the club’s instability was not quite the scourge it had been perceived as, given the abundance of honours which have flowed. “If we have a choice between stability and trophies, we’ll take the trophies,” he said.

The uncertainty is about what happens next, but for now the two are not mutually exclusive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments