Liverpool have taken huge strides on and off the pitch – and they can go even further this season

At Liverpool there is an increased sense of alignment between what is taking shape on the pitch, the direction off it and the subsequent engagement of supporters within that framework

If there is a belief in football that all other matters take care of themselves when a team thrives, the rule has not applied at Anfield for a long time, a place where everything changed between 2007 and 2010.

A joke exists, indeed, that it remains impossible to have an argument about modern Liverpool without Rafa Benítez’s name appearing at some point in the discussion.

History should reflect well on Benítez’s management during the 2008/09 season, a campaign where he led Liverpool to second in the table despite relationships in the club’s off-field operation creating a House of Cards environment where nobody involved knew who to trust because it wasn’t quite clear what the game was really all about anymore.

Rick Parry the chief executive whose rapport with Liverpool’s manager was not straightforward, would leave his position in February 2009 and even he would later describe Benítez’s relative achievement as “a miracle”.

As Liverpool’s financial position became bleaker under non-speaking owners Tom Hicks and George Gillett, the period was marked by rumours, suspicion, dire facts, protest and the establishment of new influential movements. In January 2008, the Spirit of Shankly supporters’ union gathered for the first time in the Sandon Pub.

Eight years later, the effectiveness of SOS was demonstrated when thousands of fans walked out of Anfield as planned in the 77th minute of a Premier League fixture against Sunderland in protest against ticket prices in the new main stand, the highest of which was £77. It was just three months into the Fenway Sports Group’s marriage with Jürgen Klopp and two weeks later, Liverpool were scheduled to play Manchester City in a League Cup final. The glow of exciting new bonds and possibilities did not ultimately burn brightly enough, however, to distract from core fan concerns like pricing and accessibility.

At Liverpool, a battle mentality endures for a variety of reasons but not least, as one knowledgeable supporter told The Independent, because “there is a fear that if the suits at club think they’ve won us over, they’ll slip back into their old ways”. And yet, there was also an admittance that the mood is currently a lot better than it was before – and perhaps better than at some of their more recently successful rivals – due to an increased sense of alignment between what is taking shape on the pitch, the direction off it and the subsequent engagement of supporters within that framework.

It has become more challenging to assess realities and convince of middle-grounds – that middle-grounds, in fact, might represent improvements, especially if the distance travelled is not yet quite far enough. Monday was another day of extremes on Twitter, where statements of opinion are increasingly if not almost always delivered and received as absolute truths, with outlooks either pointing towards to the best or the worst of times.

In the space of a few minutes, there had been contrasting conclusions about what has been happening at Liverpool. The first came from a blogger who was struggling to remember a point in his lifetime when “the manager, the players and the supporters,” had been as connected as this.

Directly below but in an unconnected thread came a sort of demand and decree with additional swear words from someone else, that all fans “who aren’t from Liverpool” should instead, “f**k off” because this particular author “deserved a ticket” but could not get one.

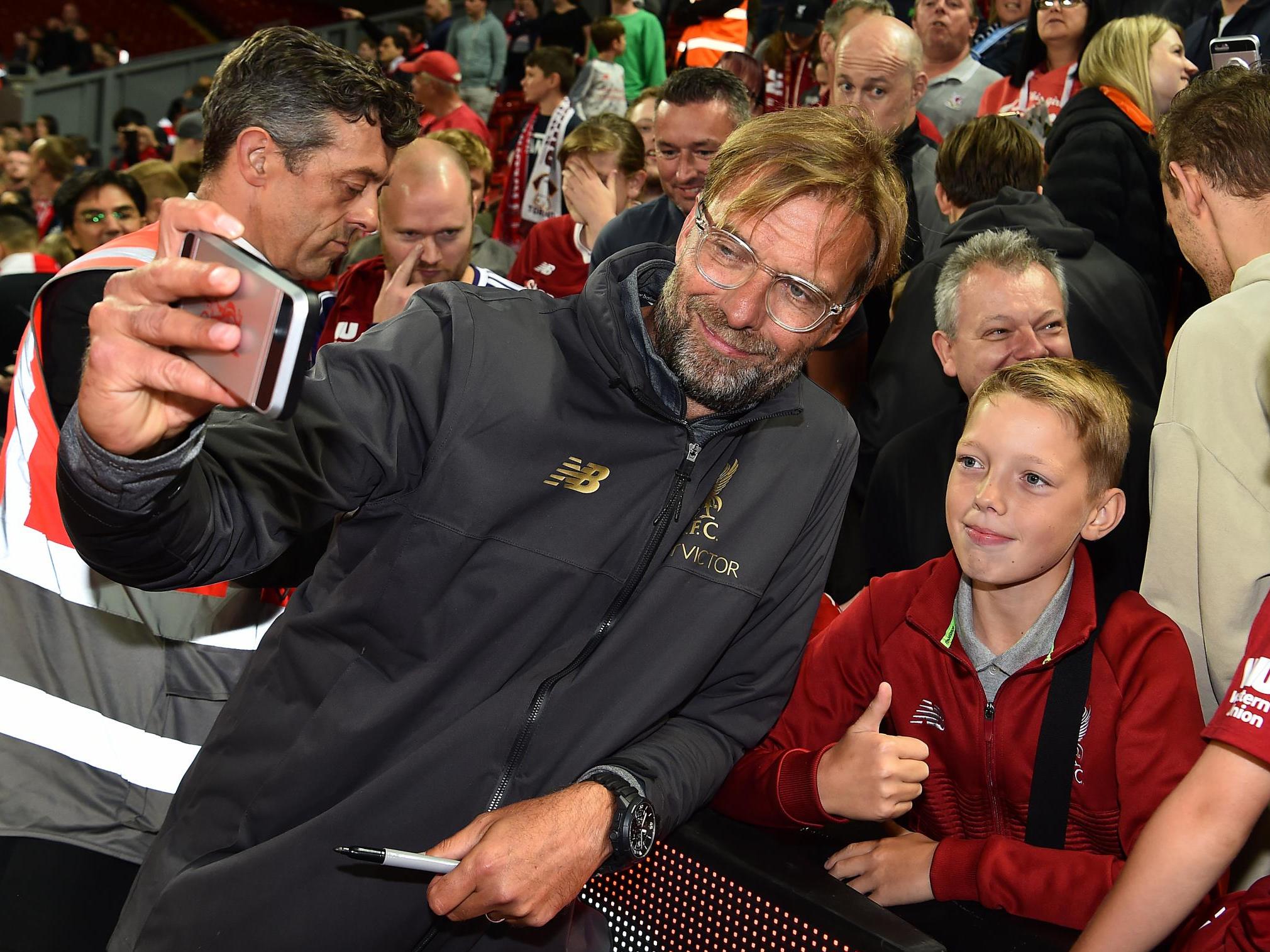

It is imaginable that the same critic would describe the scenes at Anfield the following night as mush. Klopp, Mohamed Salah and the rest of the Liverpool squad spent an hour signing autographs and handing out scarves to fans that stayed behind after their 3-1 victory over Torino in a coordinated day of activities that involved a number of free events in the city centre as well as a stage talk outside Anfield involving Klopp and James Milner.

The last time Liverpool hosted a pre-season friendly, Klopp was Borussia Dortmund’s manager and that was four years ago. Anfield was rendered unplayable in one of those summers because of the construction of the new main stand but otherwise, supporters in USA and the Far East have had more convenient opportunities to see Liverpool’s latest signings make their earliest steps in a red shirt than those living in Merseyside.

A warm-up match does not excite someone from Bootle in the same way as it might if they were from Baltimore or Bangkok and the closure of the Centenary Stand’s top tier reflected this – though it must also be considered that the holiday season is in full swing and families are away, while ticket prices for an ultimately meaningless exhibition against the ninth best team in Italy did not necessarily represent value for money. Liverpool’s willingness to try new things on returning home from their travels is an acknowledgement, however, that their approach could have been more considerate in the past and an indication that things will be different in the future.

Peter Moore became Liverpool’s latest chief executive in June 2017, introducing a mantra that the club should be represented by a “local heartbeat, global pulse.” This again will translate to some as the type of business-speak that only the cleverest of men use when calmly explaining to open-mouthed audiences at Silicon Valley-style seminars why the latest iPhone costs a couple of grand.

Trusted insiders at Liverpool describe Moore as a “different sort of chief executive”, not only because he’s the only CEO in the Premier League with a presence on social media but because fundamentally, his heart is in the right place – even if his enthusiasm and determination to fit in when he first arrived invited a degree of scepticism.

Moore grew up on Merseyside in the 1960s and though he has lived away from the area for nearly 40 years, he speaks about players like Roger Hunt, Steve Heighway and Ray Clemence like they are distant friends. Nearly 800 people work for Liverpool and Moore has introduced a routine of a “town hall” meeting every 90 days where he discusses key issues, one of them being the importance of the Liverpool Way and how it should standardly shape the approach to each day’s work for every employee.

In his attempt to project significant messages to supporters, it has undoubtedly helped him that he has not been loaded with any transfer responsibilities like either of his predecessors. This role at Liverpool has held a unique pressure considering it is the club which created the cult of the manager when Bill Shankly fought for control, someone who cast directors aside as meagre characters whose function should be limited to “signing cheques” rather than selecting teams as they did before his arrival at Anfield. Shankly still made it feel as though his achievements were in spite of these board members and this attitude embedded itself into the psyche of the Kop, something that probably made the transition into the new financial era more challenging than it was at some of clubs that ended up overtaking them.

Parry and Ian Ayre became public figures. Parry would later reflect that he tried to do too much: he was trying to sell Liverpool, he was trying to build a new ground, he was trying to negotiate with players and he was trying run the club day-to-day. Everyone had an opinion on his work and he has probably been criticised more than any employee in Liverpool’s history but Parry was a decent man who might do better if he was in a similar position with the structures in place now.

Ayre, meanwhile, was viewed with even more suspicion. In a similar role at Huddersfield Town, he had apparently made quite an impression on Liverpool’s then chairman David Moores, when the clubs met in an FA Cup tie towards the end of 1999. “Not sure about him,” was the message from Moores immediately after introductions were made for the first time, Moores being someone that Graeme Souness criticised in his autobiography, The Management Years, for not being the quickest to spot the good eggs from the bad ones.

Ayre would later arrive at Liverpool on the recommendation of Hicks, the Texan billionaire he would ultimately help remove as co-owner two and a half years later. Ayre’s own departure in 2017 felt symbolic because all of the key personalities that contributed towards the mess of 2007-10 had finally departed.

Moore was Ayre’s surprise replacement. Having led the sports division at Electronic Arts in San Francisco for the previous decade, it sounded like he was over-qualified for a job with stripped-back responsibilities, considering Michael Edwards had been promoted to sporting director and the overseer of all transfers. Fenway Sports Group did not request that he operate in a more interactive way but Moore decided it a necessary progression. He came from an industry where there was an expectation amongst gamers for him to be front of centre. If it is considered that football supporters are demanding across social media platforms, he brought with him the experience of dealing with a global gaming community that is technically savvy and online 24/7.

When Moore first joined EA, the head of communications told him that employees were not permitted to have any external interaction regarding professional matters whatsoever. By the time Moore left EA, the company developers were publishing diaries of their work, telling readers about the latest tweaks and improvements to their FIFA simulation series. Moore had taken this concept from the movie director and screenwriter Peter Jackson who kept a video diary on his production of King Kong. By the time the movie was released, Jackson’s followers felt invested in the project to the point where they had to go and see it. Jackson’s decision had been unusual because most people in his position prefer to work in secret in order to develop a sense of intrigue and yet King Kong became the fourth highest grossing film in Universal Pictures history at the time, taking in $550 million.

The summer of 2017 might end up being looked upon as the one where many things really began to change for the better at Liverpool, not only because it preceded the team’s return to elite European competition, but because off the field the appointments – led by co-owner Mike Gordon, whose own role in the decision-making process was becoming more prominent – were wiser ones.

Tony Barrett, the former Merseyside football reporter for The Times became fans’ liaison officer and though his presence now means there is a focus for complaints, therefore making it sometimes feel like there is more to complain about, he has been relentless in his attempts to bring supporters closer to the club and the team Klopp is building.

It does not help perceptions around the success of his work when an online system aimed at giving fee-payers priority access to tickets crashes on its first day as it did in July, and yet, it would be unrealistic to expect Barrett – or anyone else – to anticipate how avoid problems happening at Liverpool having been in position for just thirteen months while also addressing the common concerns that have existed for years. Sources at Liverpool believe the crash was the result of a cyber-attack.

In 2017, Liverpool also saw restructuring at their in-house media operation following the exit of London-born Matthew Baxter as digital media officer, with local and long-serving staff entrusted with creative output in a way they were not previously. Before it had felt like highly paid middle-managers with limited experience of the club or the city were too keen to follow the findings of questionnaires when deciding which content would attract foreign subscribers, rather than trusting what Liverpool actually is and the employees that know it best.

The LFCTV documentary released last month, Shevchenko Park: A Boss Session reflected the shift in mind-set. It was in Kiev’s Shevchenko Park, of course, where Liverpool supporters gathered before the Champions League final in May. Daniel Nicolson, a Liverpool supporter who edited the fabled Boss Magazine before moving into gigs under the same umbrella, suggested to the club in the aftermath of the semi-final victory over Roma that it might be a good idea to roll out an event in Ukraine that involved Merseyside bands and musicians, including the Croxteth-born Jamie Webster whose rendition of Allez Allez Allez had emerged as the anthem of the season. Liverpool would lose the final but John Power, formerly of the La’s and Cast, was not alone in his belief that Shevchenko Park was “the cultural event of the year for Liverpool as a city.”

Webster and Nicolson were subsequently invited on Liverpool’s pre-season tour of the US and hugely popular events in Charlotte and Michigan followed, with Klopp turning up at the latter to listen to Webster’s performance. Speaking on a Liverpool Echo podcast earlier this week, Nicolson told a story about how his experiences in Kiev had brought him into contact with a Liverpool supporter from Bahrain who wanted to know the name of one of the records that had been on the playlist, devised on his daughter’s iPad, in-between the acts. Deacon Blue might be from Glasgow but if you wander through Liverpool’s Mathew Street on any given Saturday night, there is an inevitability about the songs you will hear. “Now there’s a fella in Bahrain listening to Dignity because of his love of Liverpool,” Nicolson laughed.

Nicolson would suggest that Liverpool is in a better place than it was not so long ago because the club is trusting young supporters to lead the way and the explosion of fan culture is helping harvest a more genuine and attractive impression of what is really happening.

The next challenge, then, will be to ensure more of these young fans get the opportunity to attend games that really matter. Again, Liverpool are attempting to improve on this front but is it enough? In 2017/18, the Red Neighbours campaign provided 1100 free tickets to local school children, while a new price range set the cheapest match ticket at £9. It would make sense to try even harder to make Anfield more accessible because empowering supporters is a territory Liverpool seem to be able to win on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks