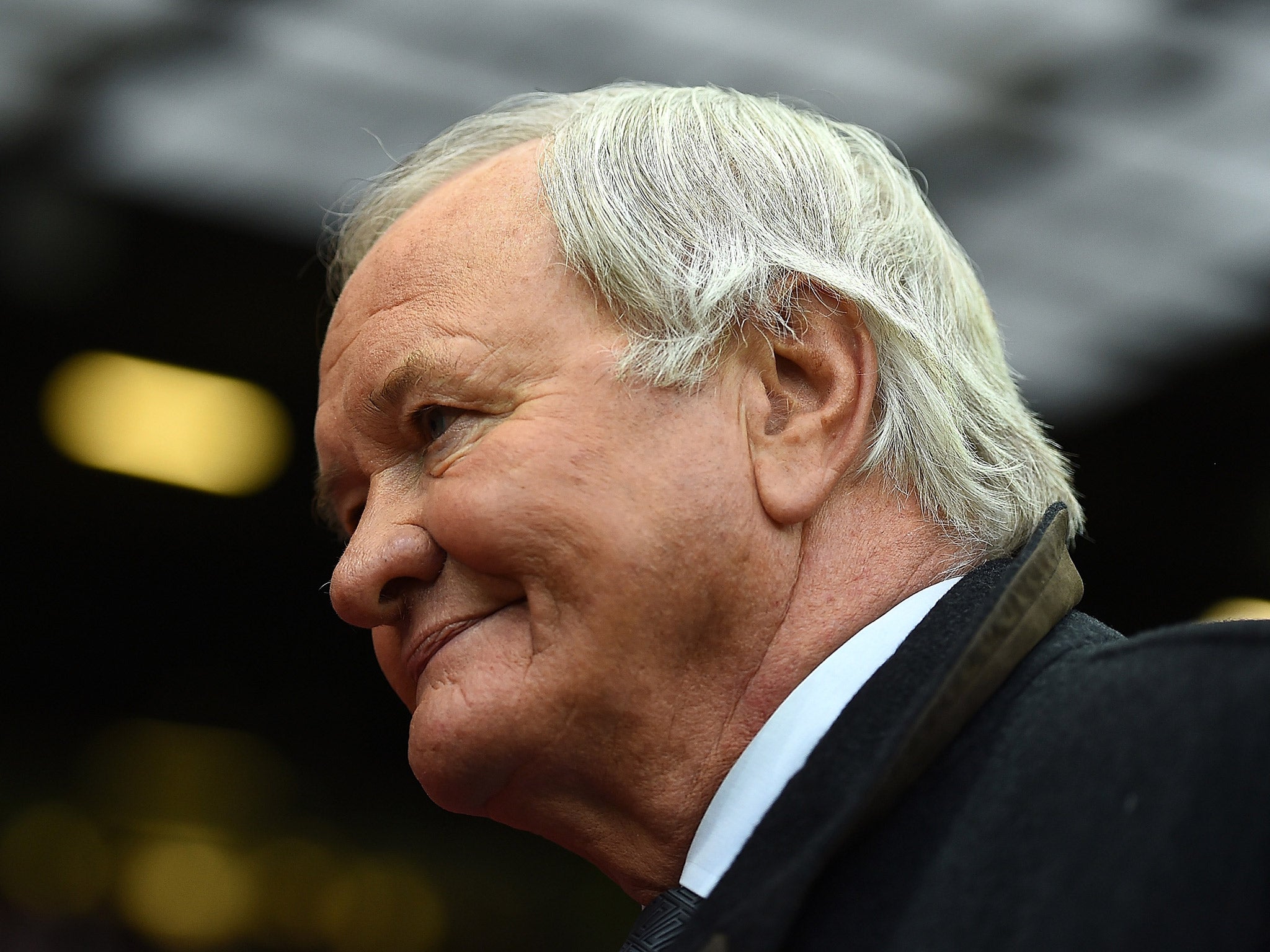

Sir Alex Ferguson 'massively exaggerated' Manchester United drinking culture, says Ron Atkinson

Ferguson titled a chapter of his autobiography 'Drinking to Failure' to describe his early days at United, but Atkinson has rubbished his claims and says Liverpool's player drank much more

Sir Alex Ferguson got it wrong when he said he inherited a club with a drink problem at Manchester United, his predecessor Ron Atkinson has declared in a new autobiography in which he says the idea his players were drinking themselves into oblivion was a “massive exaggeration.”

Ferguson entitled the chapter of his own autobiography covering his first months at Old Trafford as ‘Drinking to Failure’ and criticised Atkinson’s timing in holding a leaving party with United players “48 hours before they were due to play an away match at Oxford.”

But Atkinson insists in his book, entitled ‘The Manager’, that captain Bryan Robson had complained to him that he couldn’t get any of his team-mates to go and that other clubs, including the imperious Liverpool side of the mid-1980s, drank colossal amounts of alcohol.

“Under me Manchester United were a team that were supposed to have drunk themselves into oblivion, usually at the Four Seasons Hotel by [Manchester] airport,” Atkinson writes. “That was a massive exaggeration. Alcohol was part of the temper of the times in English football and it was not confined to Manchester United.

“I once joined Liverpool on a post-season tour to Israel and I could not believe the amounts of booze that team put away; even those you wouldn’t suspect were big drinkers, like [Alan] Hansen. Everton won two championships with Howard Kendall taking his team to Chinatown most Tuesday afternoons.”

Ferguson described how he replaced Atkinson’s “feeble prohibition” of a ban on drinking less than two days before a game with a rule that no-one must drink while in training. He said what he inherited after arriving from Aberdeen in 1986 was “almost as much of a social club as a football club.” He described Paul McGrath and Norman Whiteside as players he sold because he could not recover them from the ravages of excess drink.

But Atkinson says in the book that far from being the players who were “difficult to manage” as Ferguson had suggested, McGrath and Whiteside were “very easy to manage” and were sent into their alcohol-fuelled downward spiral when chronic injuries side-lined them. He writes that Ferguson tried to persuade McGrath to take an insurance pay-out and conclude his career was over.

McGrath’s success at Aston Villa after Ferguson had sold him demonstrated that he was not such a malign presence and lost cause, as Ferguson had suggested, states Atkinson, who later managed the defender again at Villa Park.

“Paul had pace and he had power,” he writes. “He became, for what my opinion is worth, the best centre half the Premier League has seen. He had this great trick, when the ball came across, of back-heeling it in the air with his right foot. It was because his right knee was so knackered he could barely stand on it to kick with his left.

“After I left Old Trafford, Manchester United tried to finish him. Fergie wanted to cash in on the insurance, accept his knee injury was chronic and in return for that Paul would get a pay-off and a testimonial in Dublin. Had they offered him a bit more money, I think Paul might have accepted, which would have meant his career would have been over in 1989, a few years before it reached its peak at Aston Villa.”

Ferguson viewed the renaissance of McGrath at Villa Park differently. “The jolt of having to move may have prompted some private owning up about the dangers of his downward spiral,” he wrote.

Ron Atkinson, The Manager. De Coubertin Books £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks