The debt league: How much do clubs owe?

Pompey entering administration has left other fans fretting about their team's safety. Ben Chu assesses the state of financial play in the top flight

Portsmouth have finally gone into administration. And to judge by the recent public interventions by a succession of Premier League chairmen, there is a palpable fear that other top-flight clubs could also be in danger.

In January, the Wolves owner, Steve Morgan, called for some "common sense" on Premier League finances. This month, David Gold the co-owner of West Ham and Dave Whelan of Wigan chimed in, suggesting the Premier League should impose new regulation on clubs to save them from their financial profligacy.

So owners are clearly increasingly worried about the finances of the league. But how concerned should fans be that their own club might follow Portsmouth down the road to financial ruin? The answer to that depends, in part, on the nature of the debt loaded on to each club.

Premier League debt comes in several different forms. Several clubs have borrowed directly from banks. These loans tend to come with a variable interest rate and relatively short repayment dates. Liverpool have come unstuck with this type of borrowing. The Royal Bank of Scotland is demanding that the club's American owners, who owe the bank £237m, bring in a new investor with £100m to pay down debt as a condition of rolling over its borrowings again this summer.

Other clubs have tapped the bond markets to raise money. Manchester United and Arsenal have issued securities worth £500m and £245m respectively, secured on club assets. Bonds tend to have a longer maturity than bank debt. In Arsenal's case, the club is locked in at a reasonable interest rate for 20 years. But some bonds are kinder than others. United's recent offering gives them just seven years in which to repay the money, and at a higher rate of interest.

Yet the most expensive debt in the Premier League is the £200m so-called "payment-in-kind notes" which the Glazer family took out when they acquired United in 2005. This summer the annual interest rate on that tranche of borrowing will rise to an astonishing 16.5 per cent, with full repayment due in 2017.

The accounts of many clubs, such as Fulham, Aston Villa and Wigan, show that they are beneficiaries of loans from their owners, or rather usually other companies which also belong to their benefactors. On the face of it, this type of financing looks safe and cheap as it tends to come with a very low interest rate (often zero) and no urgency on repayment. The owners of Chelsea and Manchester City have even written off their soft loans of £701m and £305m respectively in recent months, making these two clubs debt-free.

But can smaller clubs expect such debt forgiveness from their owners should they run into financial crisis or their benefactor decides to sell up? The grim fate of Portsmouth should be a warning. Alexandre Gaydamak sold the South Coast club last year, but he still wanted £28m of his investment back; a demand that seems to have helped push Pompey under.

Yet debt should really be only one part of the concern for fans. Even if owners write off what they are owed, their other function is to absorb losses made by the club and provide working capital. If that backing (often a condition of banks continuing to lend) disappears, clubs will be in big trouble. Relegation and the accompanying fall in television revenue are likely to spell bankruptcy.

So fans also need to look at the extent to which their club is living beyond its means as a stand-alone business. Balancing the books is the sign of a healthy club. By this measure – with only six out of 20 clubs showing an operating profit in their most recent accounts – the Premier League is looking desperately sick.

Manchester United

Turnover: £278.5m

Operating profit: £91.3m

Net debt: £716.6m

Interest payment: £68.5m

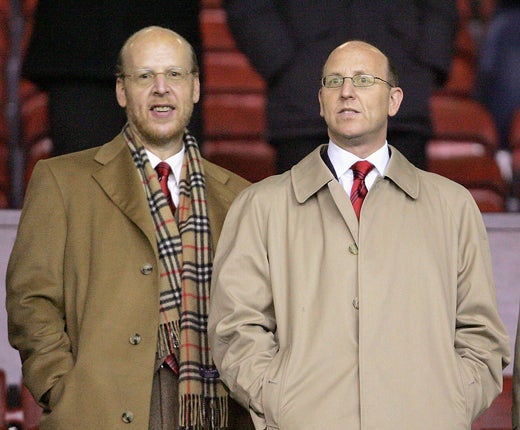

Manchester United's Byzantine finances are essentially a tale of massive profits and massive interest payments. The club's 08-09 accounts showed that the Red Devils paid £42m of interest on their £500m of bank loans. And the interest charge on the "payment-in-kind" loan, secured on the controlling shares in the club of the Glazer family, was £26m. But the PIK loan "rolls up" the interest, so the value of that debt rose to £202m in the year. Last month the Glazer family issued a £500m bond with an interest rate of 9 per cent and maturity date of 2017. The proceeds will be used to pay off the existing bank loans. The bond prospectus also makes provision for up to £70m to be taken out of the club "for general purposes, including repaying existing indebtedness". This is assumed to mean paying off some of the Glazers' PIK debt, on which the interest rate will rise to 16.5 per cent this August. The full PIK debt is repayable in 2017. The recent bond prospectus also revealed that the Glazers lost the club £35m attempting to hedge against a rise in interest rates.

Arsenal

Turnover: £312.3m

Operating profit: £58.8m

Net debt: £297.0m

Interest payment: £16.6m

A pocket of financial sanity. The club's 08-09 accounts show the outstanding value of the bonds issued to finance the building of the Emirates stadium at £244.9m. But this is repayable over a 20 to 22-year term at a fixed interest rate of 5.3 per cent. The club is also paying off some of the principal sum of the bond each year (£5.3m in 08-09), which means that Arsenal, managed by Arsène Wenger, will not be saddled with debt indefinitely. The bank loan taken out by the club with Barclays to finance the Highbury Square apartment complex, on the site of Arsenal's former ground, stood at £137m, with a repayment date of December 2010 and an interest rate of 2-2.5 per cent above the London inter-bank lending rate (Libor). Since then, however, the club has reduced the property bank loan to £47.1m, financed by selling apartments at Highbury Square for a discount. The main financial risk for the club would be a failure to fill the Emirates.

Liverpool

Turnover: £164.2m

Operating profit: £24.9m

Net debt: £261.7m

Interest payment: £36.5m

The clearest possible example of the madness of a leveraged buyout in football. Liverpool's relatively healthy operating profits in 07-08 were wiped out by interest payments on their borrowings from the Royal Bank of Scotland and the US bank Wachovia. Since Liverpool refinanced in the summer, the new managing director of the club, Christian Purslow, has claimed that the club's debt has come down to £237m.

West Ham

Turnover: £71.6m

Operating profit: –£32.8m

Net debt: £114.9m

Interest payment: £3.0m

As the new co-owner David Gold puts it: "a car crash". West Ham's 07-08 accounts showed that they owed £114.9m, more than its annual turnover. The accounts also showed the club had breached covenants on a £35m bank loan. The new repayment date for that loan, from a syndicate of five banks, is August 2011. This is, no doubt, the reason why the Hammers' new owners are urgently seeking to raise £40m from new investors.

Fulham

Turnover: £53.7m

Operating profit: –£2.1m

Net debt: £164.0m

Interest payment: £1.0m

The colossal size of Fulham's net borrowing reflects the debt it owes to Mohamed al-Fayed. The 07-08 accounts show that the club owes the Harrods owner £159m. However, this is said to be unsecured, interest-free and with no fixed repayment timetable. The club also has a £4.5m bank loan from NatWest, secured on Fulham's future broadcasting income and repayable within a year, on which it paid interest of 7.11 per cent.

Aston Villa

Turnover: £75.6m

Operating profit: –£13.1m

Net debt: £72.3m

Interest payment: £5.7m

Aston Villa's 07-08 accounts show the club has a £13m bank loan secured on the club's assets. £2.5m of this is repayable in three instalments each year until 2012. It also has a £10m overdraft. But Villa's biggest debt is to their American owner, Randy Lerner, who has lent the club £49.5m. These loans are repayable in full in December 2016. Villa paid £4.1m in interest in the year on Lerner's loan, on top of £1.37m to service the bank loan.

Sunderland

Turnover: £63.5m

Operating profit: –£2.4m

Net debt: £48.8m

Interest payment: £0.7m

Another club that survives by the grace of wealthy benefactors. The club's 07-08 accounts show that the Black Cats owed £35.2m to their immediate parent company. This was unsecured, interest-free and with no repayment date. The club also had a £13.6m bank overdraft, guaranteed by the owners. Ellis Short, the American businessman who took full control of the club last May, has given conflicting signals over how much he is willing to spend in order to push Sunderland up the table. The latest word is that he wants to reduce the wage bill.

Bolton Wanderers

Turnover: £52.3m

Operating profit: –£5.3m

Net debt: £58.4m

Interest payment: £3.9m

Not a healthy picture. Bolton rely on the backing of their owner Edwin Davies. The latest accounts show that the club owes its parent company £55.9m. Moreover, this borrowing does not come for free: £23m is repayable on demand and has an interest rate of 10 per cent. A further £11.5m is secured on future TV money. The threat of relegation is real – as is the prospect of a financial crunch.

Hull City

Turnover: £11.2m

Operating profit: –£9.2m

Net debt: £17.1m

Interest payment: £0.4m

An accident waiting to happen. The note from the accountants in the club's 07-08 accounts says that if the Tigers are relegated they will need to generate a financial surplus of £23m to avoid meltdown this financial year. And even if Hull survive in the Premier League, they will need to generate a £16m surplus. The accounts also show a £22m bank loan, with £12m repayable within a year.

Wigan Athletic

Turnover: £46.3m

Operating profit: –£17.0m

Net debt: £54.0m

Interest payment: £1.5m

The club's latest accounts make it plain that all that stands between Wigan and oblivion is Dave Whelan. The owner has put £39m into the club in the form of an unsecured, interest-free loan with no fixed repayment date. The club also has an overdraft and bank loan from Barclays of £18.7m, repayable on demand, on which Wigan paid £1.5m in interest in 08-09. The club ran at an operating loss of £17m in that year and the accounts note "further losses are anticipated in 2010 and 2011".

Tottenham Hotspur

Turnover: £113.0m

Operating profit: £18.4m

Net debt: £45.9m

Interest payment: £8.0m

Spurs have gone into debt to build a new training ground in Enfield. The club is paying an annual interest rate of 7.29 per cent on £30m of its borrowings. But it does not have to pay this back until 2024. A planned new 56,000-seat stadium should increase match-day revenues, although it remains to be seen how much the project itself will cost, or the terms of the financing.

Stoke City

Turnover: £11.2m

Operating profit: –£7.8m

Net debt: £2.3m

Interest payment: £0.5m

The Potters' 07-08 accounts showed negligible debt, but do make it clear how dependent the club is on its benefactor, Peter Coates, the owner of the bet365 online betting company. Revenue will have increased thanks to the Premier League TV money. But so will their outgoings. Last summer, the club spent £10m in luring Robert Huth and Tuncay Sanli to the Britannia Stadium.

Everton

Turnover: £79.7m

Operating profit: £6.3m

Net debt: £37.9m

Interest payment: £4.1m

Uncertainty reigns. £27m of the Toffees' borrowings – secured on future ticket sales – are spread over a relatively long period. But the 7.79 per cent interest rate meant that £4.1m of cash left the club in 08-09. The plan to increase match-day revenues by building a new 50,000-seat stadium in Kirkby was thrown into disarray last year when the Government rejected the proposal.

Burnley

Turnover: £11.2m

Operating profit: –£8.9m

Net debt: £11.9m

Interest payment: £2.7m

According to the 08-09 accounts, the Clarets' chairman, Barry Kilby, and seven other directors had the right to claim full repayment of their £6.97m loans out of the club's new Premier League revenues following last summer's promotion. The chairman is aiming for a profit this financial year to improve the club's balance sheet.

Portsmouth

Turnover: £70.5m

Profit: –£17.0m

Net debt: £57.7m

Interest payment: £6.6m

Portsmouth owed £28m to their former owner Alexandre Gaydamak, £18m to their owner, Balram Chainrai, and £5m to agents and other creditors. The club was also being pursued for £7.4m of unpaid taxes by Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs. Administration means a nine-point deduction and just about certain relegation from the Premier League. Now the fight will begin by the club's creditors to get their money back. First in line will be those other clubs still owed money by Pompey.

Wolves

Turnover: £18.2m

Operating profit: –£1.6m

Net debt: £13.0m

Interest payment: £0m

Wolves spent heavily to win promotion in 2007 and the club's 07-08 accounts reflect that. The effort was financed by new owner, Steve Morgan, who is now owed £13m by the club, although this is interest-free. Morgan tried to buy Liverpool in 2004 and says he was prepared to put £70m of cash into the Merseyside club to do so. Looking at Wolves' zero interest bill for 07-08, many Liverpool fans will probably wish he had been successful.

Chelsea

Turnover: £190.0m

Operating profit: –£11.4m

Net debt: £511.6m

Interest payment: £0.7m

Chelsea's 07-08 accounts show the club falling short of its goal of financial sufficiency. The accounts also showed a debt of £488m to its owner, Roman Abramovich. But last December the club released a statement revealing that this had been converted to equity, leaving the club "virtually debt-free". Those same results also featured an exceptional payment of £12.6m to Luiz Felipe Scolari and three coaching staff following the Brazilian's sacking as manager last season.

Birmingham City

Turnover: £49.8m

Operating profit: £13.7m

Net debt: £12.0m

Interest payment: £0.26m

Hope, perhaps, for Hammers fans. Birmingham City's 07-08 accounts reflect the golden legacy of David Gold, David Sullivan and Karren Brady. The accounts are evidence that a middle-ranking club without a ridiculously wealthy sugar daddy can run its finances in a sensible manner. The club's main debt was a £14.7m loan from its parent company, but this appears to be interest-free. Birmingham's new owner, Hong Kong businessman Carson Yeung, has a solid base on which to build.

Blackburn Rovers

Turnover: £50.9m

Operating profit: –£6.8m

Net debt: £20.3m

Interest payment: £0.8m

Precarious. The latest accounts show bank debt, secured on the club's assets, projected to increase to £20m. This loan is repayable by May 2012. The estate of the club's late benefactor, Jack Walker, has lent some £6m interest-free. But there does not appear to be an open-ended commitment to fund the club's losses. As the chairman, John Williams, warns in the accounts: "Without external funding we are inevitably moving from a trading club to a net selling club".

Manchester City

Turnover: £87.0m

Operating profit: –£34.2m

Net debt: £194.4m

Interest payment: £14.4m

The normal rules of business do not apply to Manchester City. The latest accounts show a company with a turnover of £87m running at an operating loss of £34m and with an accumulated debt to Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi of £194m. Since then, the club has spent £117m on players, including Emmanuel Adebayor and Carlos Tevez. But last month Sheikh Mansour converted Manchester City's entire £305m debt to him into equity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks