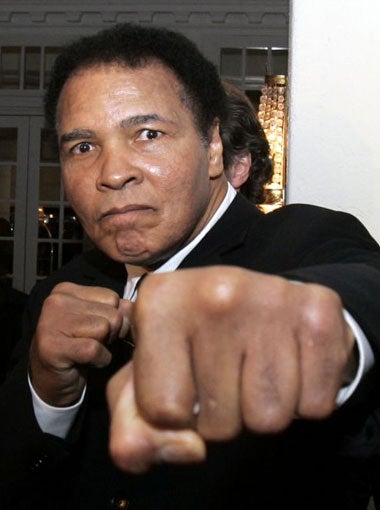

Boxing: Ali at 65

Muhammad Ali's birthday today is a time to celebrate his genius - and to reflect on the terrible sadness of his life

There was a time, and it is not so distant, when it seemed almost enough to have Muhammad Ali in the same room, the same arena. However much he was reduced, however fleeting the evidence that came in some childish magic trick or mischievous eyes that still shone out from a sudden, mugging glance, you could, if you liked, believe there was still something left of the uniquely superior spirit that captivated the world.

Today, though, the truth on his 65th birthday is that it is no longer possible to scratch through layers of memory and troubled conscience for even such thin and self-deceiving consolation.

Maybe it was always so. Perhaps for the last 20 years, some people, and especially those who came to Ali only on the descent from glory, have seen through too sentimental eyes a beautiful human wreckage when really it was just wreckage. No longer is it easy to doubt the evidence provided by his most recent public appearances. The magic of what he was, what he represented to members of every race and creed, no longer has the bare sustenance of a party trick or a sudden, tremulous stance.

It is clear he is fast declining now as those around him make the last "greening" of an unrivalled reputation, and whatever is written on the certificate, however equivocal the blame placed on the sport which was his vehicle for a greatness that swept him beyond every boundary, every prejudice on his way to becoming the most charismatic - and most fiercely loved - man of the 20th century, there is no longer any question about how and where and when the process gathered pace.

Some of the milestones and the place names will always be central to the legend of The Greatest. Madison Square Garden, 8 March 1971 when, after three and a half years of exile after his refusal to go to war in Vietnam, and at the age of 29, and with his legs no longer a wonder of athleticism he went into the ring with amazing haste to produce with Joe Frazier one of the greatest fights of all time. Ali lost for the first time but over 15 rounds no fighter ever said more about the endless welling of his spirit and the resilience of his talent. Kinshasa, Zaire, 30 October 1974, the Rumble in the Jungle, the victory over George Foreman that staggered the world in its brilliant pragmatism and warrior improvisation. Quezon City, the Philippines, 1 October 1975, when in the 14th round Frazier's superb trainer Eddie Futch halted the fight because his man's rage to go on had not deflected him from the fact that he could no longer see. It was after this fight that Ali said he had felt close to death.

However, it was maybe two years later, back in Madison Square, against the heavy-hitting Earnie Shavers that some of Ali's entourage began to understand that he was indeed into the process of destroying his health.

Certainly it was this fight which showed beyond any doubt that Ali's endless courage had become his last and most dangerous asset, that the damage of the years had carried him to his most critical point.

To be in New York at that time was to know beyond doubt that you had arrived at perhaps the most pivotal phase in the most astonishing story sport would probably ever know.

Few disputed that the great fighter was possibly one stumble away from the abyss. Later, it was revealed that Ali also carried that brooding sense into the ring. The veteran boxing writer, and Ali confidant, Jerry Izenberg recalled 14 years later, "I remember sitting with Ali in the old Hotel Statler across the street from the Garden. It was a day or two before he fought Shavers. We were alone and Ali said to me, 'Do you know how many years I've been fighting? Do you know how tired I am? Do you have any idea how hard that man is going to beat on my head tomorrow night?' And then I asked him, 'Why do you do it?' He didn't really give me an answer, although it was clear that money and glory and other people's expectations were all part of it.

"And then I said, 'let me tell you something. Do yourself a favour. Sit down and play back the roach-spray commercial you just made, because I listened to it 10 times before I could make out the word 'fog.' I couldn't understand what you were saying. And then take any of the tapes you made over the years and listen to your voice the way it used to be.' And I told him, 'You know there was once in this world a pathologist named Martland. And Martland might not have had all the answers, but it was his theory that if you stop fighting tomorrow, and never go into the ring again, it will take two more years for the disintegration of your brain to stop. That's something you should think about after you fight Earnie Shavers tomorrow night. Because it would be a horrible tragedy if you were to wind up punch-drunk, which is what Martland's syndrome is all about.'"

Martland's or Parkinson's syndrome? Boxing's most obdurate defenders will still opt for Parkinson's and point out that Ali's father, a signpainter in Louisville, was afflicted with the same illness, but however much you care for the oldest and most dangerous of games, it is impossible to shake off the memory of that night in the Garden when Shavers, the hard, shaven-headed man from Ohio, came out punching with such withering power. Looking back it has always seemed less of a fight and more of a parable about the folly of pride, and if not that, of the corrosive power of any addiction, in Ali's case that of a glory that only came from the basics of danger and challenge.

Shavers hit Ali so hard in the second round for a moment it seemed that boxing's most famous building was shaking on its foundations. Ali admitted later that no one apart from Frazier had hurt him so much.

It dictated his fight, which was mostly about evasion and smoke and mirrors, deft jabs and clever retreat and, from time to time, a point-stealing flurry of a combination, a feint and a hook. Then, at the end, Ali reminded every one of the audience, the old fight men and the newly initiated, why it was that the Garden was jammed to bursting point and that three-quarters of all switched-on televisions in the United States were tuned to the fight. Ali rose up in the last round and fought with all the majesty at his command, which despite the pain and that weariness he confided to an old friend, was still an awesome amount.

It was as if Ali had, briefly, stopped time, arrested his own physical decline and any seepage of nerve, and later Shavers, at first convinced he had won, spoke generously. He said, "Fighting Ali was hard for me to do because he is such a good man. He is my idol. Before we fought, he helped me out several times, letting me use his training camp for free, giving me advice on what to do against other fighters. I love him personally, and you hate to see a legend defeated. But at the same time I was fighting for my family and myself.

"It was a good fight. In the second round I hit him with a right hand that hurt him. He wobbled, and then he wobbled some more. But Ali is so good at conning I thought he was playing possum with me. I didn't realise how bad off he was. Later, when I watched the tape I saw it, but at the time I was fooled. He can do that; it was why he is Ali and why he could beat me."

In the victorious dressing room Ali screamed for the lights to be turned off. He said the light was like needles in his eyes. His fight doctor, Ferdy Pacheco, handed in his resignation. He said that Ali was killing himself, bit by bit. "Everything is being damaged," said Pacheco. "Your brain, your kidneys, your liver, even your bowels. I can't be part of this anymore." Teddy Brenner, the Garden match-maker, shook his head and said, "I never thought I'd live to see the day when Muhammad Ali's greatest strength was his ability to take a punch." Pacheco's pleadings went unheeded, even after he sent to the Ali camp the most disturbing laboratory report.

Pacheco recalled, "The Shavers fight was the final straw for me. After the fight Dr Nardiello, who was with the New York State Athletic Commission, gave me a laboratory report that showed Ali's kidneys were falling apart. Instead of filtering out blood and turning it to urine, pure blood was going through. This was bad news for the kidneys and since everything in the body is interconnected, we were talking about the disintegration of Ali's health. I wrote to Ali and attached copies to Herbert [manager Muhammad], Angelo [trainer Dundee] and Veronica [Ali's then wife] and I didn't get a single reply."

Ali had four more fights, losing three, to Leon Spinks, his former sparring partner Larry Holmes and the tragically starred Trevor Berbick, who was recently murdered in his native Jamaica. The Holmes fight, on the back lot of Caesars Palace, was really the end. Ali looked like a miracle when he came into the ring. But the effect was entirely cosmetic. He had been filled with diuretics, and later it was alleged that before the fight Ali had been tested at the famous Mayo Clinic, and that a report suggesting brain damage had been suppressed. Ali was a shell and Holmes pounded him for 11 rounds. Then it was over and even some strong men had tears in their eyes, tears of regret and maybe no little shame that they had any played any part, however minuscule, in the over-reaching of the greatest man they were ever likely to see.

One summer's day before the Holmes fight, Ali was encountered in his training camp in Deer Lake, a remote and beautiful location in Pennsylvania. He talked for hours about his last stand against Holmes, how he would overwhelm the psyche of a good but overmatched opponent - and the sweep of his career. He insisted his visitor join him for lunch. It was a good day, his faithful retainer Gene Kilroy revealed later, simply because he had been visited by a sportswriter. "Every day," said Kilroy, "he keeps asking, 'where are those guys, why aren't they coming?'"

They would never come again, not in their old volume, at least, and not in their expectation of deeds and style beyond the common imagination. Kilroy sat in the dusk and talked of earlier, more tumultuous days; he recalled how it was when the airplane was on its descent into Kinshasa, and Ali shouted back down the cabin, "Hey Kilroy, who do my kinfolk down there hate most in all the world?" Kilroy guessed that it might be the Belgians because of their often cruel colonisation of the Congo. When a huge crowd gathered at the airport Ali came down the steps of the plane with his fist in the air and with the declaration, "George Foreman is a Belgian."

That is the Ali Kilroy, and all those who were touched by a man who could create gridlock in any city street on earth simply by taking a stroll, will conjure for himself today. The toast will be the one that never varies, the one to grace and courage and a humour that lit up the world. And the one, maybe, to an understanding that sooner or later the world does indeed break everyone, in some way or another, and that sometimes it is those who have given more than anyone else who are hurt most.

Maybe it also means that today's celebration is inevitably poignant. It is that no one ever gave more of himself than Muhammad Ali - and that anyone who saw him will never forget the most fabulous gift.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks