Gene Kilroy: The man who made Ali's Rumble in the Jungle

Kilroy was there, 40 years ago, when Muhammad Ali knocked out George Foreman to reclaim the world heavyweight title in Zaire. Ali’s close friend, known as the ‘Facilitator’, speaks to Steve Bunce

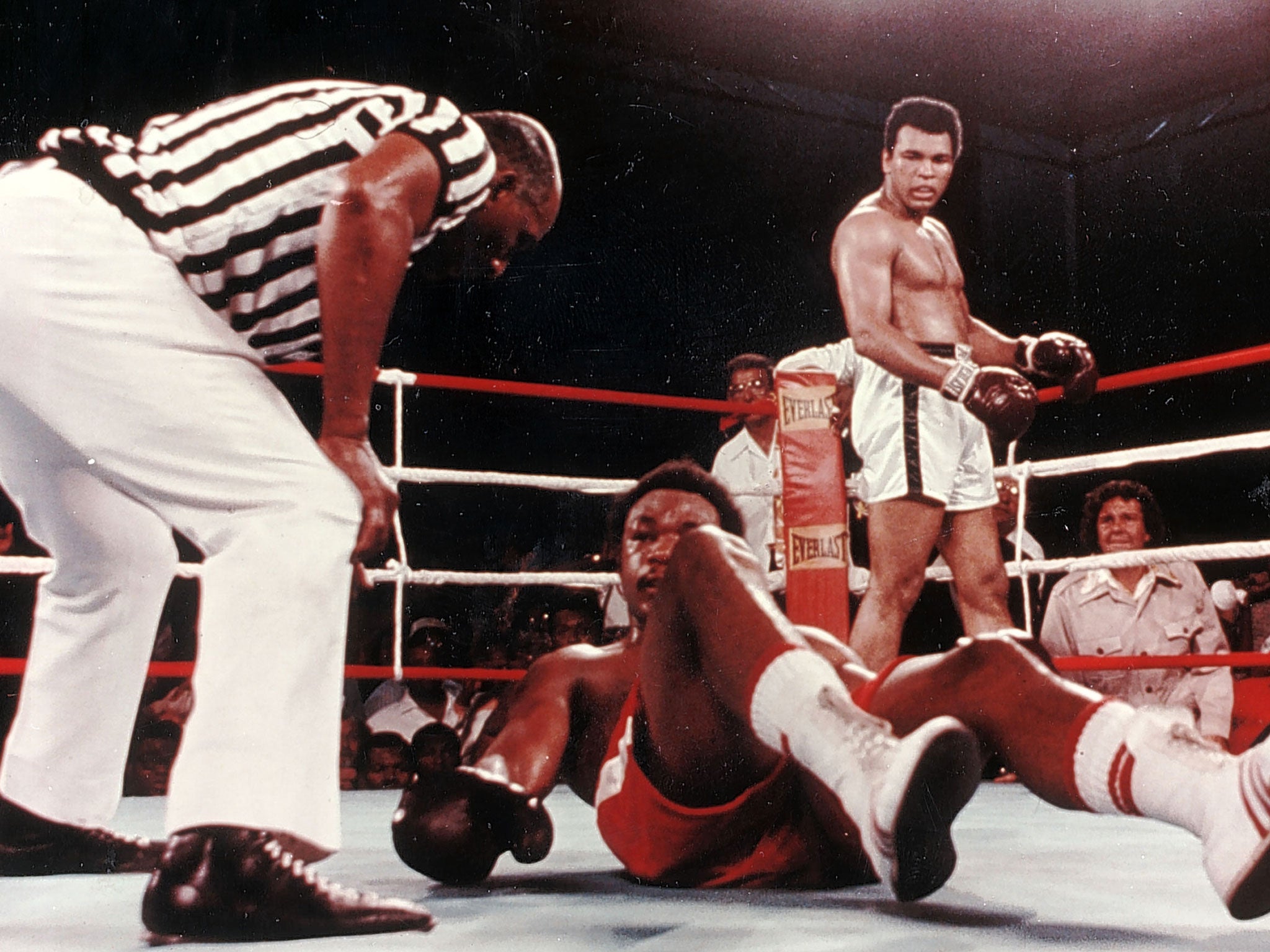

He had a perm, wore a safari suit and was first in the ring when George Foreman failed to beat the count at dawn in the Rumble in the Jungle, but you have probably never heard of Gene Kilroy.

He was Muhammad Ali’s business manager and made the champ’s camp move; he greased the parts, he patted the palms and he was known, at the time of the great fight in Africa 40 years ago, as the Facilitator. He was then and he remains now Ali’s friend, part of a tiny inner circle who each wore diamond-studded rings of fellowship.

“I reached Ali and I could see he was exhausted,” says Kilroy. “He just wanted to sit down. ‘Let the crazy people celebrate. I’m tired, Gene.’ He said that to me. In the ring people were going crazy, but I stayed with Ali.” He did: take a look at the film, the pictures from the night, and look at the concern on Kilroy’s face.

Kilroy had met Ali at the Rome Olympics and joined the circus during the boxer’s forced exile, leaving a job inside MGM’s marketing division. The pair became firm friends. Kilroy carried the coffin when Ali’s mother died and by the time the fight with Foreman arrived they were close.

“We were in New York before leaving for Zaire and Ali decided that he had to talk to Cus D’Amato,” says Kilroy. “I was in his hotel room and I called Cus and I said, ‘I got the champ for you’, and gave Ali the phone. Cus told him how to beat Foreman. He told him to take away Foreman’s strength and turn it against him. Ali always listened to Cus. Cus was a great guy. Ali really needed that lift.” Most people in Kilroy’s Ali stories are “great guys” and Kilroy has a lot of Ali stories. Ali with Elvis, Ali with presidents, Ali with victims and heroes.

On the plane to Africa it was Kilroy who told Ali that the Zairean people disliked the Belgians. On arrival, Ali told the African press Foreman loved the Belgians. It was Kilroy who told President Mobutu Sese Seko’s henchmen to confiscate Foreman’s passport when the fight was delayed. “I said that if George leaves, there will be no fight and that the President will look bad. I told them to get the passport. I saved the fight because George wanted to leave, he wanted out of Africa and out of the fight,” insists Kilroy.

The fight was meant to take place on 25 September but eight days before the first bell, scheduled for 3am for the American audience, Foreman was cut above the right eye from a wayward elbow by one of his six sparring partners.

It created panic and dreadful confusion when it was thought that the cut would take two months to heal and require a dozen stitches. It was then that Kilroy intervened. “The break was good; it meant Ali could get some rest because there were fewer requests,” adds Kilroy.

The cut was treated by Foreman’s trainer, Dick Saddler, and closed and healed without a single stitch when the veteran applied his secret “Saddler Special”. The fight was soon back on, with a new date but no new posters, and the preparations in the gym never halted.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“Ali continued his walks, continued meeting the people. It was what we did and Ali always held kids – he was away from his own for so long in training camps,” says Kilroy.

After 55 days in Zaire it was finally time for the heavyweight championship of the world to take place. Foreman, the unbeaten champion, was a massive favourite and people feared for Ali’s life. A lot of convenient revisionist thinking has since been written, but as they left their compound in N’Sele, 40 miles from Kinshasa, in darkness there was real dread from the silent occupants in the cavalcade of cars. “We all loved Ali and nobody wanted to see him get hurt; against George, we all knew there was a danger,” says Kilroy. Ali was 32, seven years older than Foreman, and he had lost twice and shown signs of decline – the fear was real.

Inside the changing rooms the mood failed to lift and people got on with whatever jobs they had in their own silence. Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer, fiddled with his swabs, placing and replacing the adrenalin sticks, used if there is a cut, in tidy lines to avoid talking about the horrors to come.

Kilroy was sent to Foreman’s changing room to witness the gloving process. The corridors were silent, there was no joy. Kilroy was morose as the minutes ticked ever closer to the start of the massacre. Saddler and Archie Moore – the great Archie Moore, who had once worked with Ali at the Bucket of Blood gym in San Diego – were pacing Foreman’s room.

“I smell death in the air,” Moore said. There was a feeling of invincibility about Foreman, who had just ruined Ken Norton in two rounds – the same Ken Norton who had gone 24 rounds with Ali and beaten him once. Foreman was a beast, Ali was his prey and Kilroy’s heart was hurting for his friend as he traipsed back to Ali’s dressing room.

“I got back and the mood had not changed, it was worse,” Kilroy continues. “Ali turned to me: ‘What that nigger say?’ I had to tell him, I loved him and couldn’t lie: ‘He said that he is going to make orphans of your children.’ There was just a second of silence and then Ali jumped up. He was throwing punches and hollering and [assistant trainer Bundini] Brown got to hollering and I thought then that he had a chance. I hoped, more than thought.” A few minutes later the team made their way to the ring in the middle of a platoon of soldiers. Ali in the white robe, Kilroy in his safari suit and Brown and Dundee, the corner duo, focused on their long night once they climbed through the ropes.

It was a torturous night for Kilroy, standing at ringside, often holding the ropes as Foreman’s sickening power shook Ali, the ropes and the ring. But the predicted massacre unfolded in reverse and by round seven Foreman was gulping and frothing like an “overgalloped horse”, to borrow from Norman Mailer.

In round eight, Ali knocked out Foreman to become the heavyweight champion of the world again. It remains the most dramatic ending in boxing and Kilroy was most certainly there.

Kilroy managed to get a film of the fight and it was shown on the flight out of Africa to Paris and again on the flight to Chicago. The passengers stood and cheered the ending and I think we have been standing and cheering ever since.

Seven years later, in the Bahamas, it was finally over for Ali, Kilroy and the men who rejoiced in Africa. Ali was brutalised by Trevor Berbick over 10 rounds and Kilroy’s ulcers were bleeding and he was puking up blood again. He had done the same when Larry Holmes, a paid sparring partner in Zaire, had beaten Ali the year before. Kilroy was there until the very end, the man with the perm and the safari suit and only survivor from Ali’s inner circle.

When presidents and kings come to Vegas, Kilroy is always on call

Gene Kilroy moved from Muhammad Ali’s facilitator after the gut-wrenching pain of his last defeat to play a crucial role in the development of the Las Vegas way as a fixer, greeter and friend to the city’s highest rollers.

Kilroy has worked in many of the fight and gambling city’s top casinos, fixing lines of credit, hopping on the in-house jet to collect big spenders and making sure that they had tickets for shows, which I have always considered a euphemism.

I have sat with him late at night in casino coffee shops and, even as mobile phones took over, he still had a proper phone brought to the table. He would palm out 10 dollars to the greeter, the kid pouring the water and the waitress in an endless line of tipping. Once installed at the table he would call the switchboard and tell them: “Hi, this is Gene Kilroy, I’m in the Brown Derby.” That was it, that was enough and, I swear, the phone would start ringing in minutes as people tried to reach the ultimate facilitator.

He drove all over town in a white Mercedes convertible that once belonged to Tom Jones, a real friend, and most nights for the last 33 or so years he patrolled the thick-carpeted walkways between gambling tables, restaurants and executive lounges at either the Luxor, New York, New York or the MGM, where he still maintains a role as a consultant.

“You know what happens in Las Vegas?” Kilroy asked. “In Las Vegas people make offers – I have moved casinos. People know I help people and I have helped presidents and kings and paupers. That was how it was with Ali and that is how it has been with Las Vegas.”

Since starting in Las Vegas as an executive host, all the establishments that have hired him did so with the knowledge that when Ali comes to town, Kilroy will be busy. Kilroy and his friend, Ali, together every time that the boxer has visited the city, talking in hushed whispers in giant suites at the MGM that were buzzing with the champion’s magic tricks.

Kilroy has stood sentinel over a declining flock since that last calamitous fight, and in addition to the big-name deaths from the inner circle, there are others, lesser members of the swollen entourage, that Kilroy has helped and buried. “This is a great life,” Kilroy told me one night in the MGM’s VIP suite. “But, I tell you this, Ali burnt me out. There is nothing left to see.”

Steve Bunce

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks