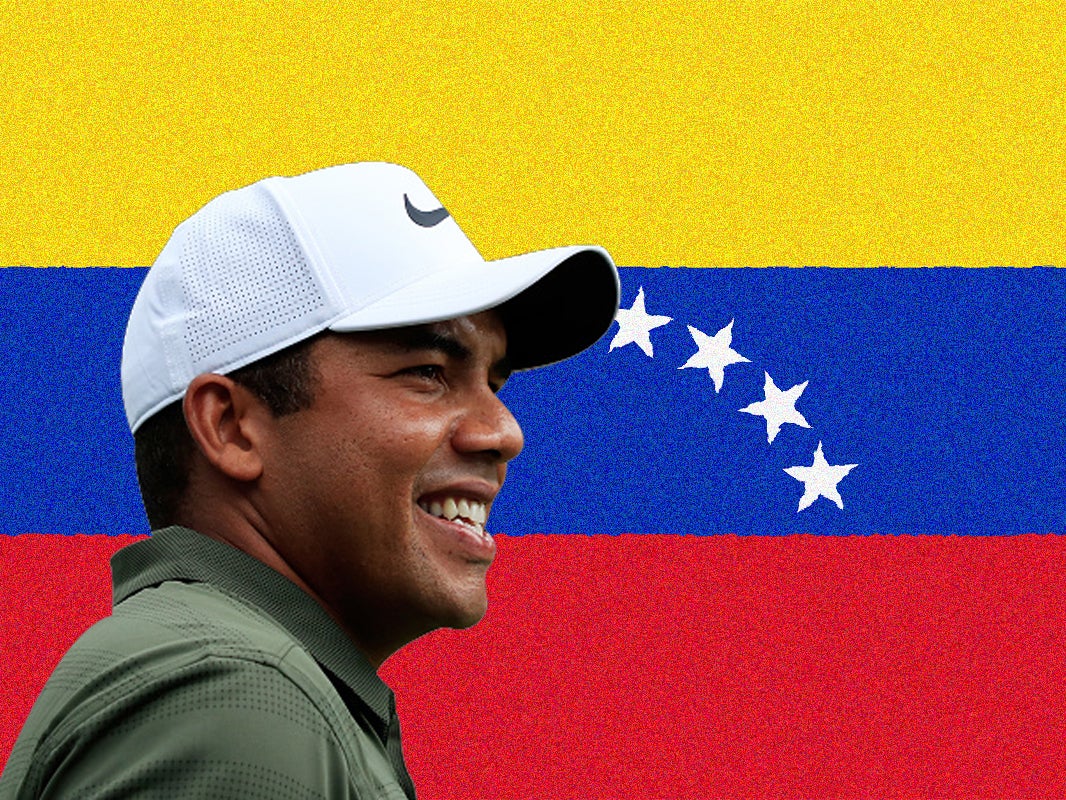

'The people have to rise': Jhonattan Vegas on Venezuela's crisis and why he hopes to one day be able to return home

Exclusive interview: Unable to return home, Venezuela's greatest golfer dwells on a country collapsed into chaos

It’s been four years and one month since Jhonattan Vegas last set foot in Venezuela. Smuggled in on a private jet, shielded from armed kidnappers by commandos in the backseat of a bulletproof SUV in Caracas, searching for a semblance of home. “Between Venezuela now and when I grew up?” he says. “It’s heaven and hell. You would think we are at war the way people are fighting for their lives. ”

The only Venezuelan golfer to ever win a PGA Tour event, last year Vegas was forced to move the last of his three brothers out of the country. “His kids struggled to find food,” he says exasperatingly. “They couldn’t even leave the house.”

In all likelihood, the earnest 34-year-old knows he may never be able to return home. Just last month, two of the country’s high-profile former Major League Baseball stars, Luis Valbuena and Jose Castillo, were killed after their car was ambushed by highway robbers. Speaking exclusively to The Independent in late 2018, in the wake of an assassination attempt on Nicolas Maduro, Vegas reflects on a country descending into disarray.

“It’s chaos,” he continues. “It’s a situation which has become life or death. The only job is to survive. Either not to get killed by criminals or not to get ill.”

Thousands flood out of the country via the 200km ‘Hunger Highway’ to Brazil every day. To the children from the slums, who walk the asphalt road in bare feet, Vegas is a faraway idol; the man who made it from the oil camp to America with a suitcase, a set of hand-me-downs and beat up golf clubs.

In Venezuela’s cities, shops have been looted, supermarkets are left unmanned with empty shelves, there is little medicine and often no running water. When nothing is available, the money Vegas would send back home was no use. “$100 goes a long way,” he says. “But not if you can’t find food.”

“There aren’t even antibiotics, not even things like Ibuprofen. If you get sick, you die. It costs people more to go to work than what they earn. Children can’t go to school because they don’t eat. Newborns are dying every day. The government is not willing to do anything to help people. It boils my blood.”

On Wednesday, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans took the streets calling for President Nicolás Maduro to step aside. With the US interfering, Russia threatening to cut oil ties, and Juan Guaido’s right-wing government set to seize power, the country’s future is in perilous limbo.

But in the El Guire slum where Vegas’ father, Carlos, was born in the foothills above Caracas, they waved flags from the windows and lifted liberty banners in the streets. Nobody is sure what change will bring, but the consensus is that it cannot be worse.

“The country has reached that point. This is a regime willing to do anything to keep power,” Vegas says, drifting back to the – in his eyes – staged assassination attempt on Maduro last August. “There’s no law. The country is collapsing.”

“The people have to rise. The government aren’t willing to have elections democratically, they have the military and everyone else under control. But it could be very ugly because they are willing to use arms on their own people.”

Fourteen people were shot by police during Wednesday’s protest, while others were sprayed with teargas. In 2018, 163 protestors were killed as the military continues to back Maduro’s regime.

In Maturín, a petroleum kernel 500km east of El Guire where Vegas was taught to play golf by his brother with a rock and a stick, 700 protesters were besieged by the army and trapped for hours in the town’s cathedral

A twenty-minute drive out the city is Quiriquire, the oil camp where the Vegas’ lived alongside 150 families, and where Carlos was once a restaurant manager at the Exxon Mobil plant. Next door is the nine-hole golf course, built for the factory’s employees, where Jhonattan would practice in the musky evenings.

But after Carlos signed the Tascón List – a declaration to denounce then president Hugo Chávez in 2003 – the plant was expropriated and the golf course was closed as part of the late president’s war on the ‘bourgeois’ sport. Now, it is just an expanse of disused unkempt grass.

Out of a job, Carlos used his savings to pay for flights to California so Jhonattan could play in the Junior World Golf Championships – the zenith of U18s golf won by the likes of Tiger Woods, Phil Mickelson and Ernie Els. But Carlos’ intention was that his 17-year-old son wouldn’t return.

On the way back from the tournament – where Vegas finished sixth, despite using his hodgepodge clubs and wearing thread worn shoes – Carlos and Jhonattan travelled to Houston to visit Franci Betancourt, a former Venezuelan pro who used to teach golf to children in the oil camps.

“Franci, I want Jhonattan to stay here,” Carlos said.

“You mean for lunch?”

“No, forever.”

Unable to speak any English, soon Vegas was competing on the state’s amateur circuit. Already 6’2” and 200 plus pounds with thickset shoulders and a close-cropped buzzcut, the local papers in Maturín referred to him as ‘Tyson’ Vegas.

Handpicked for a scholarship at the University of Texas, even then he couldn’t afford to make phone calls home. It took three years after graduating in 2008 for Vegas to win himself a coveted spot on the PGA Tour. But in just his second event on the circuit, he won via a playoff at the Bob Hope Classic. The grand prize? $900,000.

After the win, even Chávez called to congratulate him. “He beat all the gringos,” Chávez said. “He is the pride of Venezuela.” Still, though, it would be 11 months before he could safely return home to celebrate.

The win made Vegas an idol across Venezuela. A beacon of hope and success for those fleeing out of desperation rather than promise. A platform he’s used to speak out against the people’s strife. “Yes, it would be easy in my case to stay quiet,” he admits. “I have a decent life in the US. I don’t have to get involved, but Venezuela is hurting. I hear on a day-to-day basis what’s happening, how complicated things are. I love my country enough to speak.”

Two more wins and hundreds of tournaments later, though, Jhonattan’s success has also made it hard for him to ever return home – a $10m target on his back – at a time of such consuming tension. The protests may continue for months, the unrest for years. Even then, there are no guarantees of stability. “To not even be able to go to your country, see your old friends, the people you grow up with because you put them at high-risk.” That is the greatest pain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks