When the drugs deny real winners their golden moment

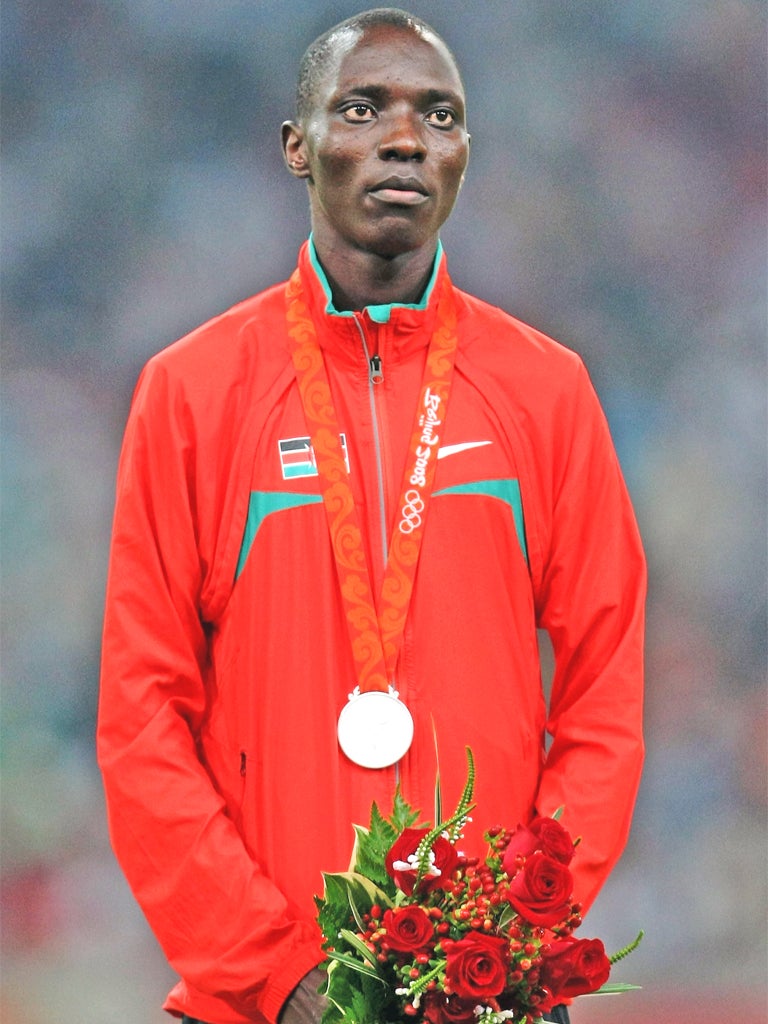

Asbel Kiprop runs in Edinburgh on Saturday having only just received his rightful 2008 Olympic medal. The fight goes on to avoid similar travesties in 2012

For Sebastian Coe, it was rather different. The future peer of the realm and head of the London 2012 organising committee was able to fully savour his golden moments as a winner of the men's Olympic 1500m title twice-over – sinking to his knees and kissing the Lenin Stadium track in Moscow in 1980 after avenging his 800m defeat against Steve Ovett, and turning to the media tribune in Los Angeles four years later and wagging a finger of admonishment at those who had dared to write him off.

For Asbel Kiprop, the middle distance man who bears the mantle of reigning Olympic champion at the metric mile distance at the start of this London Olympic year – and who will be on British soil later this week for a first-footing spin in the Bupa Great Edinburgh Cross Country meeting on Saturday – the golden moment was somewhat removed. It came three weeks ago in a function room at the InterContinental Hotel in Nairobi, three years and four months after the 2008 Olympic 1500m final in Beijing.

Kiprop's appearance on these shores at Holyrood Park on Saturday, 202 days before the opening ceremony of the 2012 Games, comes as a sobering new year reminder that not all that is destined to glitter at the London Olympics in the summer ahead will be of the 24-carat variety – and that some of those outshone in the heat of the showpiece occasion will ultimately prove to be the golden boys and girls of London 2012.

Kiprop did not cross the finish line first in the 1500m final in the Bird's Nest Stadium on 19 August 2008. The tall, willowy Kenyan – just 19 at the time – chased hard up the home straight but could not quite close the gap on Rashid Ramzi.

Instead of following in the footsteps of the great Kip Keino, the first Kenyan Olympic 1500m champion, at whose high performance centre he happens to train in Eldoret, Kiprop was initially awarded the consolation of the silver medal. Ramzi, born and raised in Morocco, paraded around the track as Bahrain's first Olympic champion in any event. He stood proudly on the top step of the rostrum as the Bahraini anthem played at the medal ceremony and was feted as a national hero on his return to the Gulf state.

It was not until the following spring, in April 2009, that news emerged that Ramzi had tested positive at the Beijing Games for CERA – Continuous Erythropoietin Receptor Activator, a third generation version of the banned blood boosting drug EPO. It was not until July 2009 that his 'B' sample was tested and found to be positive. And only in November 2009 was Ramzi formally disqualified as Olympic champion and Kiprop declared the winner.

Even then, it took until 8 December of the year just gone for Kiprop to receive his gold medal. There were no masses to acclaim him – just a handful of invited officials and journalists at a hotel in central Nairobi. At least the Kenyan flag was raised and the national anthem played – and, fittingly, the belated prized was presented by Keino, chairman of the Kenyan National Olympic Committee, whose stunning 1500m victory at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968 was one of the defining moments in the great African running revolution.

"It has taken three years to get this medal, but justice has finally been done," Kiprop, now 22 and also the world 1500m champion, said. "It is not the way I wanted to be an Olympic gold medallist. It would have meant more to win on the track in the natural way but I am happy because I have got what is mine.

"I will go down in the history books as the first Kenyan to have ever received an Olympic gold medal on Kenyan soil. To have the national anthem played for me as an Olympian in my own country was a great moment in my career."

Kiprop's first race as the possessor of an Olympic gold medal is the international 3km race on the south side of Edinburgh on Saturday. Watching him from the sidelines at Holyrood, in the shadow of Arthur's Seat, will be a retired British athlete who was once presented with an Olympic silver medal in front of a handful of club runners and a few bemused dog walkers on a damp, chill April day in Battersea Park.

With 5,000 tests due to be conducted on athletes from all sports at the London Olympics – a 10 per cent increase on Beijing, where there were 20 positive tests across the board – the local organising committee hope that the 2012 Games will not be blighted by drugs. As Mike McLeod can testify, though, the cheaters have been denying the honest Olympians their moment in the sun for decades now.

McLeod is 59 now and a grandfather. The owner of a printing business on Tyneside, he will be in Edinburgh to watch his youngest son, Ryan, compete in the 8km international race. At the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles McLeod senior finished third in the 10,000m final – behind Alberto Cova of Italy and Martti Vainio of Finland. Two days after the race and the medal ceremony, it was announced that Vainio had tested positive for the anabolic steroid Primobolan. He became the first track and field medal winner to be disqualified at an Olympic Games.

McLeod was promoted from third to second. He received his silver medal five months later, prior to the start of the 1985 AAA Championship 10km road race in Battersea Park. "I drove down from Newcastle with my coach, Alan Storey, to collect it," the runner known in his prime as "the Elswick Express" recalled yesterday. "Maybe they could have waited until the Seoul Olympics in 1988 and presented it to me in the stadium there.

"They could have done that with Kiprop: waited until the 2012 Games and presented him with the gold in the Olympic Stadium, in front of the world. At least he was on the rostrum for the medal ceremony in Beijing, like I was when I got the bronze in LA. The athletes I feel sorry for are those who finish fourth and don't get on the rostrum at all."

McLeod has reason to feel sorry for himself. Cova, winner of the gold medal in that 10,000m final in 1984, admitted in later years that he had been involved in a blood-boosting programme administered by the Italian track and field federation. The practice – of removing blood cells and re-injecting them prior to competition – was not outlawed at the time of the Los Angeles Games. Still, McLeod can claim to have been the first untainted finisher in that race.

He has spent 28 years despairing at the honest toilers in his sport being continually cheated by chemically-powered fraudsters. "I've always thought that, once caught, these people should be banned for life," he said. "It's sickening for those who spend their lives training hard and doing it the right way."

It must be sickening indeed for Asbel Kiprop that he might have Rashid Ramzi in his way when he defends his Olympic crown in London in August. Now that the International Olympic Committee ban on returning offenders has been lifted, having served his regulation two-year suspension, the dethroned, disgraced 1500m champion from 2008 is free to go for gold again.

Tainted triumphs: When drugs made the crucial difference

Carl Lewis and Big Bad Ben

According to the record books, Carl Lewis is the only sprinter to have successfully defended his Olympic 100m crown though Usain Bolt stands to become the first to cross the line in a final as a back-to-back champion. Lewis won the title on home soil in Los Angeles in 1984 but was beaten by Ben Johnson in Seoul four years later. He was presented with the gold medal in a clandestine ceremony underneath the main stand in the 1988 Olympic Stadium after his Canadian rival tested positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol.

Marion Jones and the ghost race

After Marion Jones was stripped of her gold medals in 2009, the International Olympic Committee decided not to announce a revised winner of the women's 100m final from the Sydney Games in 2000. Katerina Thanou, the Greek sprinter who was suspended after missing a drugs test on the eve of the 2004 Games, finished second in that race. Tanya Lawrence of Jamaica was third.

The untouchable East Germans

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, documented evidence was uncovered of a state-administered drugs programme involving leading East German athletes who could be identified by codes or in some cases letters kept in Stasi files. Those named in public include track and field Olympic champions Marita Koch, Barbel Wockel, Jürgen Schult and Thomas Munkelt and the swimmer Petra Schneider, who beat Britain's Sharron Davies to the gold in the 400m individual medley in Moscow in 1980. No retrospective action has ever been taken to remove East German medal winners from the Olympic roll of honour.

Simon Turnbull

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks