McCain, the maverick who became national treasure

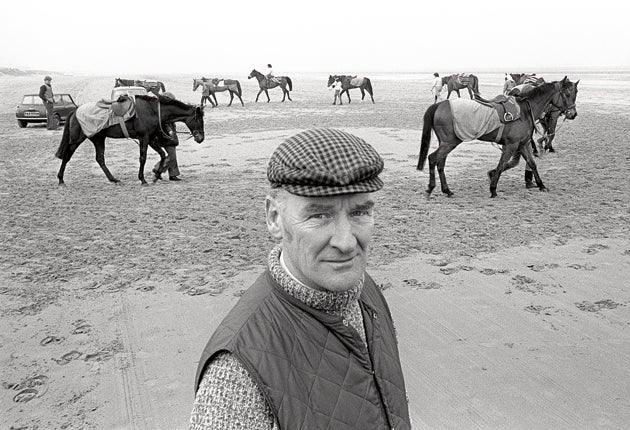

Red Rum's trainer, who died yesterday, embodied the spirit of the steeplechase he made his own, even when at odds with an age of change. Chris McGrath recalls a unique talent

If Ginger McCain happens to have written his own epitaph, the engraver will want to be sure he is paid by the word. So long as he brings a broad mind to the job, however, he might soon decide it is worth doing for nothing. For whatever he might gain in wisdom, he will surely receive ample reward in laughter.

McCain so enriched the British Turf that you would forgive him nearly anything. And that was just as well. He had an incorrigible instinct for discovering and provoking the most squeamish sensibilities of a society he joyously deplored as prudish, precious, effete.

Only those guilty as charged, however, would ever take his fulminations too seriously. And these will never have noticed the rheumy glint of gratified self-parody in the eyes of the old man. Automatons, he would reason, are designed for winding up.

As it turns out, our last conversation could scarcely have been more redolent of the unique Ginger spice. But then he was always putting on a show. Practically everything he said had the instant patina of famous last words. By the same token, it overstates matters considerably for anyone to claim a "conversation" with Ginger. Even so, on this occasion, his declamatory tour of the crowded lawn behind his house identified him as a man who could now die happy.

Everyone was celebrating the consummation of an Aintree legend. The previous afternoon, Ginger had watched his son, Donald, win the Grand National with Ballabriggs. For 27 years after Red Rum, Ginger had endured the widespread suspicion that he had stumbled across a horse so freakish that even a Southport taxi driver couldn't prevent him winning three Nationals. Some, by this stage, had concluded that Ginger was not so much an institution as a man who should be locked away in one. And then his temerity found fresh, unanswerable expression. In 2004 he won the race again, with Amberleigh House.

Two years later, aged 75, he handed over his training licence to Donald. They had long since abandoned the old cobbled yard in Southport, where Red Rum was stabled behind a car showroom, and come to the stately parklands of Cholmondeley, in Cheshire. But what was really going upmarket now was the quality of the horses. By the time they returned to Aintree in April, Donald had already far surpassed his father's achievements in every other measure – whether by the number of races won, or their stature. All that remained was for Donald to show that he had also inherited the definitive, Aintree gene, among the others that must have been culpably overlooked, or so it now seemed, in the old man.

Still tall, florid of feature and plain of speech, Ginger held court to group after group on the sunlit lawn. Finding two or three journalists together, he recalled lying in a hospital bed last Christmas Eve. "I was in a six-bed ward," he said. "Within a week four of the other buggers had snuffed it. I told the doctor he wouldn't be getting a 100 per cent record out of me, and was out of there that night. I'm not kidding myself, I'm 80 years old, but I always said I'd like to see that young 'un win a National before I turned my toes up. And I've done it now."

He lowered his tone confidentially. "I never dreamt I'd say this, but he is a good trainer." A pause, a theatrical grimace. "Now if he'd just take up smoking or womanising, something like that, so the pedigree could come out..."

No less typically, the champagne fuelled indiscretions that might have caused uproar if misused by those he took into his trust. We watched him led across to a live television link, and shuddered to think what ingenuous scandal he might volunteer. Nothing frightened Ginger, and sometimes that made you want to protect him – especially if you were Beryl, the fierce little woman with whom he shared an endless pantomime of mutual despair. "Harvey Smith told me to get rid of Beryl," Ginger would pronounce. "Because she is too old to breed, and too savage to keep as a pet."

But Beryl would always try to grab the tiller whenever she sensed him sailing into hazardous waters. And, one way or another, they have certainly raised a composed, reflective son. The joy of Ballabriggs had been diluted by a couple of horrible accidents in the National, and Donald recognised his obligations that morning. He addressed the potential misapprehensions and distortions with patience and intelligence. As he did so, it was difficult to resist a sense that his father's story had now been told enough.

Ginger knew as much himself. True to form, he complained bitterly that the "do-gooders" would now meddle with the National fences again. Didn't they realise that making them easier would make them more dangerous? "It's the bloody speed that kills," he exclaimed. Sure enough, modifications to Becher's Brook have since been announced. With his health declining, Ginger will have perceived that the tide had turned, leaving him high on the beach. Better, he declared cheerfully, for a steeplechaser to go out in full cry, gloriously alive, than to end up "like me, old and doddery, waiting to be put down".

But however much he raged, it was never against the dying of his own light. Rather it was against the fading world about him – an ageing England that had lost its virility and pride. His vexation would be gaudily embroidered in reckless complaints about the sacred rights of foxes, hares and, above all, women. As for health and safety, "all these bloody safety rails everywhere" – why, a couple of horses galloping loose through a crowded enclosure would soon teach people to take responsibility for their own preservation.

"What can you respect these days?" he would grumble. "You're not allowed to believe in yourself, in your country, anything." But he had one abiding comfort. The British institution he most adored would be eternally synonymous with a horse that found unaccountable fulfilment in a trainer who had taken 12 years even to win a selling plate. McCain typically had no more than two dozen horses in his care. His greatest adventures had seemed destined to remain behind the wheel of his taxi: as when he once chauffeured a lion to London, or took Frank Sinatra around Southport in search of a hairbrush. ("An insignificant little man," McCain remembered. "I always thought Bing Crosby was better.") But he had seen, in boyhood, the shrimpers' carts in the bay, and how the horses' old limbs were soothed by the salt water. And so he would gallop Red Rum across the great strand. He always said that the horse would never have lasted anywhere else. "I needed Red Rum," he would admit. "But he needed Ginger McCain, and he needed Southport."

Ginger's legacy has long seemed guaranteed. Nobody who saw Red Rum will forget him, while McCain Jnr has literally made a name for himself. But Ginger would tell you how everything he cherished will eventually disappear, like weathered letters on his tomb. They have done away with so much already. His true bequest, for better or worse, is the way we were. And his last plea would be to remember – for all the imperfections he magnified so exuberantly, in himself and others – how to enjoy the times we have.

Grand master: Ginger McCain's four national triumphs

1973 Red Rum

One of the greatest of all races – at a time when Aintree was threatened by development – as Red Rum just catches the runaway top weight, Crisp, in the process smashing the track record by 19 seconds.

1974 Red Rum

A year after receiving 23lb from Crisp, Red Rum returns with 12st on his back, giving weight even to the Cheltenham Gold Cup winner, L'Escargot – but still wins by an seven easy lengths.

1977 Red Rum

Though he has twice returned to finish second, few believe Red Rum can roll back the years at the age of 12 – but he takes it up at Becher's second time and romps home by 25 lengths.

2004 Amberleigh House

McCain's attempts to win another National have looked increasingly forlorn, but suddenly Amberleigh House – a distant fourth turning for home – begins a late charge and secures McCain's place in history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks