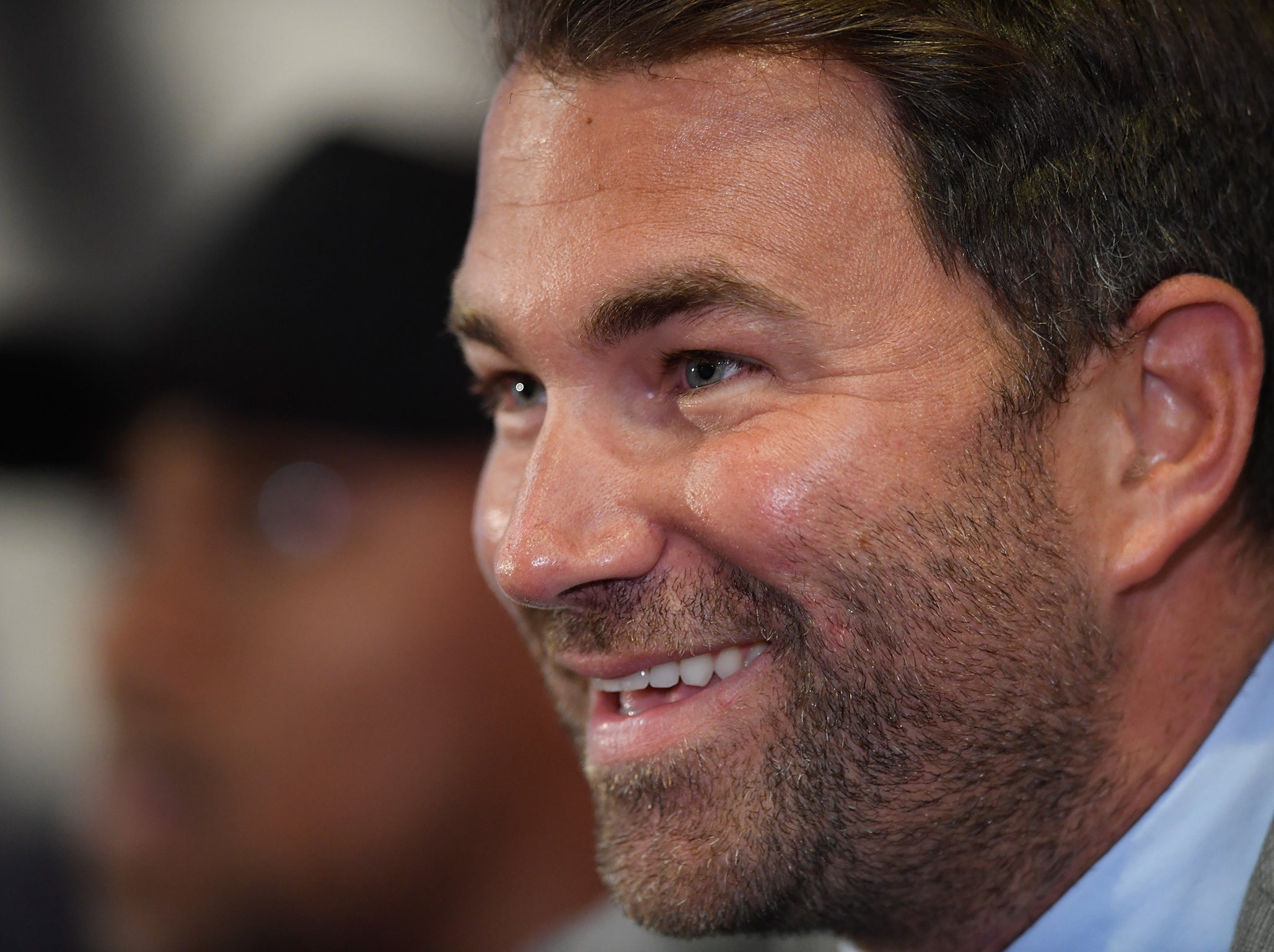

Why rugby league would be wise to resist master marketer Eddie Hearn’s beguiling offer of glitz and gimmickry

The Jonathan Liew column: This week Hearn suggested he might be minded to turn rugby league around. But does the sport really need his unique brand of cynicism and puffery?

There’s a particular defensive move in boxing - and I’m not sure what the technical term is, but I’m sure there is one - that has become increasingly prevalent in the sport over recent years. It’s the limp, half-hearted stance that Eddie Hearn gets into when he’s trying to separate two fighters who are brawling at one of his press conferences.

Well, have you ever seen a man more cruelly, existentially conflicted? Torn between the moral obligation to forestall the ensuing violence, and the inescapable knowledge that bad blood sells fights? And so in much the same way that the security guards on Jerry Springer would never actually drag their feuding guests apart, but simply stand in front of them while they screamed about murdering each other, Hearn makes only the most perfunctory of efforts at actually stopping the brawl.

Call it the Hearn Shuffle. We saw it when Dereck Chisora threw a table at Dillian Whyte a year ago. And again before that, when Tony Bellew and David Haye got a bit shirty the face-off. And it happened again this week - I know right, what are the chances? - at an event to promote Amir Khan v Phil Lo Greco at the Liverpool Echo Arena in April.

Essentially, Lo Greco made some jibe about Khan’s recent marital difficulties, and Khan got up and threw a glass of water at Lo Greco, and then they lunged at each other in a manner that a neutral observer might almost describe as spontaneous.

Hearn moved in like an apathetic cat. A little flap of the arms here, a little swivel of the shoulders there; evidently shocked and appalled by this sudden turn of events, and the publicity and attention it would doubtless generate for a fight that would probably not have registered on most people’s radars. If you look closely, you can almost see him mouthing: “Oh no. Oh dear. The fighters are brawling. Again. This is truly awful.”

It’s a mental image worth holding on to as we discuss the other reason Hearn is in the news this week. In a radio interview, Hearn suggested that he might be minded to turn his promotional talents in an entirely new direction. “We’ve got a habit of turning sports around,” he explained. “When you’ve got a sport as big and powerful as rugby league, I feel we could do the same.”

Clearly the timing of Hearn’s comments was no accident, coming ahead of the start of the new Super League season on Thursday night. And for a sport as perennially insecure and angst-drenched as rugby league, the idea of becoming the latest vassal state of the Hearn empire holds a certain spangly allure. Look at what Eddie’s father Barry has done, for example, for darts: a British pub sport terraformed into a global circus. Or snooker, whose long-term decline has been arrested, if not quite reversed.

But perhaps, on reflection, we need to be a little careful of what we wish for. Peer a little closer into the success of the Hearn dynasty, and what emerges is a talent for promoting and marketing sporting events, as opposed to sports per se.

What links darts and snooker and boxing and pool and table tennis and gymnastics and all the other arms of the Hearn stable is that they are self-contained spectacles. All the competitors are in the same place, under the same roof. Print some posters. Get the beers in. Sit back and watch the punters roll in.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Rugby league, on the other hand, has not just one focal point, but many. Quite apart from the 12 Super League teams scattered across England and France, and the 169 games they will play against each other over an eight-month season, you have the hundreds of teams that make up the pyramid beneath them, right down to the local grassroots clubs, the kids’ teams, the old couples who have been making the tea at places like Flimby and Wyke for the last 65 years.

This is, in essence, not simply an elite roadshow but an entire sport. Is Hearn interested in all of it, or just the little sliver at the top? Perhaps the future of rugby league is simply the Magic Weekend every weekend, in a different city. Perhaps the time is ripe again for talk of mergers and brand new teams, a concept last seriously raised in 1995, when proposals to amalgamate Hull and Hull KR, or mush Castleford and Wakefield into a ‘Calder’ franchise, were understandably and justifiably laughed out of the room.

For this is the thing about rugby league: it is a clash of proud clans, but also a clan in its own right, and you tinker with that dynamic at your peril. The violence and the rivalry and the bad blood is there, and acknowledged, but never fetishised.

I remember seeing Ben Flower’s shocking punch on Lance Hohaia in the opening minutes of the 2014 Grand Final between Wigan and St Helens, and remember too how in the days afterwards, the St Helens chairman called for calm and patience, appealed for Flower to be supported and rehabilitated and reintegrated into the rugby league family. I invite you to imagine how Hearn might have handled the situation alternatively.

Nobody, of course, would deny that the marketing of rugby league in this country could do with a rethink. The game’s relationship with Sky Sports, for example, has turned into something of a sexless marriage over recent years. Hearn is right, too, when he observes that the sport seems to produce fewer household names than it used to, that sponsorship interest is fading, that audiences are flatlining.

Yet there are a legion of reasons for this, from the decline of the international game, to the dominance of Australia’s NRL, to the natural entropy that afflicts all medium-sized sports in the digital age. Rugby league is no longer simply competing with union and football and cricket, but Netflix and YouTube and simply lying on the sofa all night in your underwear scrolling through Instagram whilst eating cereal straight out of the box. Hearn’s magic touch, considerable though it is, will change precisely none of this.

Essentially, the Hearn method constitutes an extreme form of negging: convincing sports that they’re ugly, and yet full of potential if only they wore this top, or did their hair slightly differently. The early signs are that it may be working. “We’re open to ideas,” said Ralph Rimmer, the acting chief executive of the RFL.

The question now is whether rugby league is secure enough in its own values and its own worth to resist his charms. Does the sport really need the cynicism and the hard sell and the puffy hype and the confected drama of big-time boxing? Can the glitz and gimmickry that have proven so successful in darts really attract bumper crowds to Craven Park and The Jungle? Do these places even have a place in Hearn’s vision? Is there another way?

It’s easy to be tempted by the gilded promises and the smoky dreams of a master marketer. But there’s a reason they’re in marketing in the first place.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks