David Flatman: Some role models fall short – why does it make us angry?

From the Front Row: Rehabilitation won't take place in rugby - it is just too public and too brutal

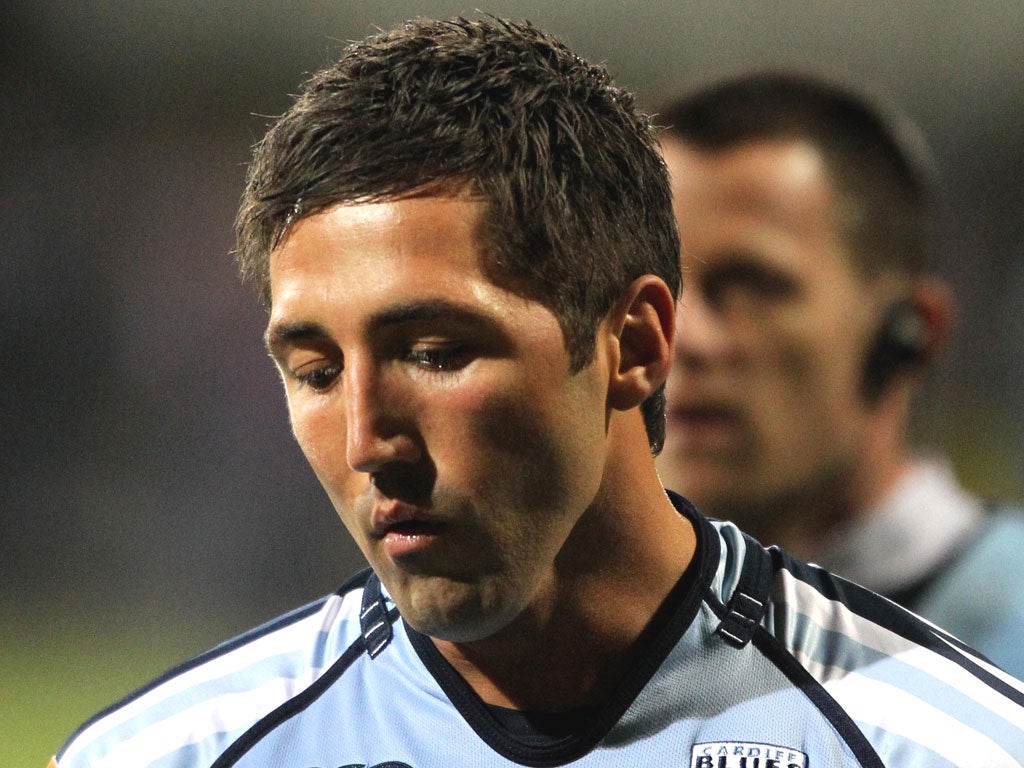

A year or so ago, I wrote a column about Gavin Henson. To be honest, I wanted to write it as I felt strongly that this was a fragile bloke in need of something other than another inky hammering. In summarising my thoughts I suggested that his legacy would be one of a flower among house bricks; a beautiful athlete who made those around him – at whatever level – look as cumbersome as he was accelerative.

Sadly I was wrong. It still, for good or bad, is not in me to rip Henson to pieces for being less perfect than we wanted him to be. So many of the men we see becoming sporting heroes and role models manage naturally to toe the line and behave in a manner we deem appropriate. Inevitably, there will also be some who fall short, in our minds at least.

What I cannot understand, however, is why this makes people so angry. I know that here I am separating myself from what seems to be a large portion of the reacting public, but it is what I feel. Henson is a bloke who, when in shape and in the mood, was better at rugby than most others. When he was not in the mood he was either crap or somewhere else.

To me, this is nothing more than a huge shame. Had I been the person paying his wages I might feel somewhat aggrieved at this point, but I was not so I do not. Neither do I feel let down, for what did he ever owe me? (Actually he once told an interviewer that we rugby types only drove Audis because they were nearly free and reportedly cost us all the best car deal in history, so you might say he owes me a car.)

As a child, somebody told me that if I was good enough at rugby to make it my career then I must. "Think of all the boys who aren't good enough," he said. "You owe it to them." I always regarded this as rubbish. Play because you love it, not because somebody else thinks you ought to love it.

Henson did not love it enough. He was brilliant, but he did not love the game, the lifestyle and his team-mates sufficiently to curb who he really was. Perhaps his steadfast refusal to consider the potential consequences of his actions was a side effect of always having been the star player for whom the rules always seemed to bend. Or, just as likely, perhaps he is just not very bright. Either way, the equation by which players like Henson are valued – one which stacks his value to the team on the field against the amount of time it takes to manage him – has swung so far from where it began that he is now practically unemployable.

Three top-level coaches and man-managers – at Saracens, Toulon and Cardiff – have now seen their attempts to tame the beast fail. All three were experienced, worldly team men. But Henson just could not and would not do as he was told. It seems to me that he must either have a sort of chemical release in his brain that renders him unable to behave himself, or a real feeling that no matter what he does he will be alright because, hey, he has the talent no coach would sack off. Whichever it is, it has led to his downfall.

A fellow (and departing) Cardiff player was straight on to Twitter once the sacking was announced telling whoever cared that what Henson had done on the plane was not worthy of the punishment, but this missed the point and revealed a narrow view of the world.

By the time Henson arrived at Cardiff he was already the sort of risk that would cost any recruiter sleepless nights. While being totally frank, most players will have boarded the odd early-morning flight with a few units too many in the system, but when Henson did it he proved that, despite assurances made, he could not change his ways. He could not say no. This was the moment his past came back to bite him.

I think the only person he has really let down is himself. Selfishly, I feel disappointed that I might never watch him play again, but that remains my problem, not his. Instinctively, though, I want him to get better. But I do not think this or any behavioural rehabilitation will take place in rugby; it is just too public and too brutal.

I hope it does not take place on national TV either, and that he realises his inner wellbeing and contentment will always be more important than a few quid. He might not be an alcoholic or drug addict but the anti-social nature of his actions will cause him grief wherever he decides to land next.

I hope he seeks the opinion and guidance of someone who shows compassion but also tells him the firm truth that he will need to survive in the real world. Ultimately, he needs to disappear under the radar. Not for our good, but for his.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks