A broader scope for your studies

An increasing number of British students are turning to European institutions for a top quality education, without the huge debts

Dark, cold days, expensive alcohol and an unfamiliar language haven’t frightened Devon-born student Cai Weaver away from Finland. In fact he has not looked back since embarking on a Masters degree in one of Finland’s largest cities and at one of its most renowned universities, and his Finnish is coming along nicely too.

“Quite frankly, I didn’t want any more debt,” says Weaver, 24, who is studying international relations at the University of Tampere. English-taught postgraduate study in Finland is free for all EU nationals.

His student loans already amount to around £30,000 from his undergraduate days at Aberystwyth University. Weaver has saved money for living expenses from his job last summer and has a paid internship with an EU organisation in Finland as part of his studies.

While a weak pound makes some things expensive, accommodation and travel are cheap and he’s living on about half the €600 a month the university estimated he’d need.

Later in his course, which like many continental European Masters lasts two years, he’ll complete an internship with a Russian university. “It’s not just about the money though. I thought that an international education would look far better on the CV and teach me more about life than continuing education in the UK.”

Weaver looked at universities in Greece, the Netherlands and Germany before choosing Finland, where his aunt and uncle live.

Tampere, which is hosting eight UK postgraduates and has around five applicants for every international place, also offers students such as Weaver free Finnish lessons and an effective support network.

Weaver is blazing a trail that many UK postgraduates will be likely to follow, given the whopping debt they will carry from their undergraduate years. Postgraduate education elsewhere in Europe is heavily subsidised and often costs a fraction of UK prices – and it’s increasingly being taught in English.

While few UK postgraduates have yet to choose continental Europe, they should, says David Hibler, Erasmus programme manager at the British Council. “Large multinational employers expect people to have a career that moves between different countries. Studying abroad allows you to develop a cultural awareness and independence you might otherwise not achieve. It adds another dimension to your CV.”

So thought UK postgraduate Ed Forrest, founder of Educate for Life, which runs an innovative school called Hunar Ghar in rural Rajasthan, India. He’s studying for a two-year Masters in international co-operation in education and training at Paris Sorbonne University and, unusually for an English speaker, he’s chosen a course taught entirely in French. “It feels lovely to be studying and not racking up £5,000- worth of debt. But learning is more than just doing a related course – the best way is to put myself in a learner’s position again. This means I can better relate to children as learners at Hunar Ghar. Language-wise, it’s hard but it’s getting easier.” Each year will cost him just under €500, including a social security payment.

While universities on the Continent may lack the cachet of the UK system, whose institutions regularly rank among the best in the world, what they offer in perspective and value for money is looking more and more appealing. Germany, for instance, which offers free or low-cost Masters programmes, is the most supportive for international students, according to a British Council survey.

As with many European programmes, most German Masters courses last two years. This appealed to Manchester University graduate Ellie Rea, from Edinburgh, who is studying for an MSc in neuroscience at Charité University Hospital, Berlin. She wanted broader laboratory experience than UK courses provided. “I started looking in the UK, but was disappointed by the small scope of programmes on offer. Most involve a single year working on one project. I was thrilled to find a course that suited me [in Berlin].” Unlike some of her peers, she speaks some German. “But half my coursemates seem to be getting on with little or no language.”

EU postgraduates in many German states need pay only enrolment fees each semester. Rea pays €500 a year in total, which entitles her to heavily discounted travel. As with the UK, postgraduate admission isn’t centralised, but the German Academic Exchange Service (www.daad.de) gives a comprehensive overview and details of courses.

Were it not for the low fees or the grant he received from DAAD, postgraduate Andy Murphy says he would probably never have studied beyond his first degree in linguistics.

He receives €750 a month to study for a Masters in linguistics at Humboldt University of Berlin and, unlike most international students, he studies in German. “Do be prepared to be left to your own devices at German universities, although the academic standard is undoubtedly high... It can be quite easy to get lost: you are expected just to know information or find it out for yourself.”

Any would-be postgraduates daunted by the prospect of tackling another language could consider Sweden, which offers hundreds of English-taught Masters, all free, and where many locals speak fluent English. International applicants for Masters in Sweden are up 24 per cent on 2011 and around 800 people from the UK have applied so far this year.

Many hope to go to Lund University, where there has been a 30 per cent increase in UK applicants for Masters courses. The university is a strong research institution in a city popular with students. International candidates comprise half its postgraduate cohort. Applications are open twice a year, once in winter, and again from March to 15 April. See www.studyinsweden.se for more details and scholarships.

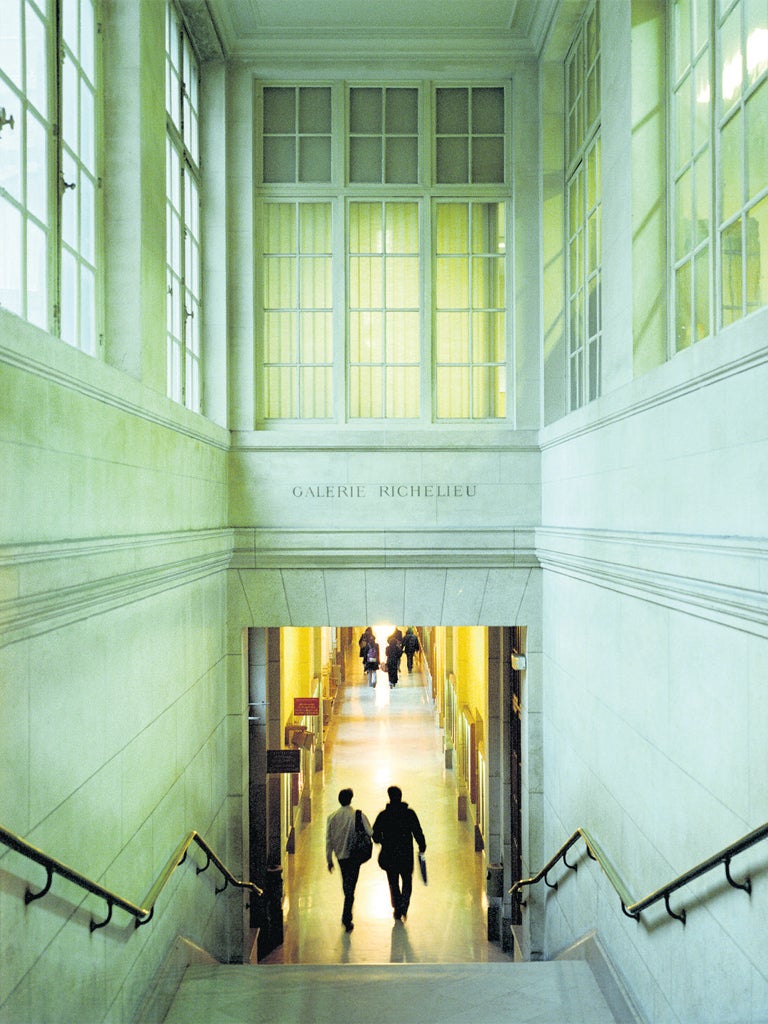

In France, too, where state universities charge a modest €245 for Masters programmes, candidates must apply during March and April, or earlier if they can. Paris draws the most international applicants, but they also look at France’s other large cities, such as Lyon and Bordeaux. A specialised Parisian international university, Sciences Po, is attracting a large share of UK applicants. See www.campusfrance.org to find out more about French higher education and the applications process.

Negotiating the often labyrinthine structure of university hierarchies in other European countries is best done via official government sites.

Many provide comprehensive information, including details on a number of scholarships for international postgraduates. The EU’s Erasmus Mundus (eacea.ec.europa.eu) programme, which funds postgraduate study at European universities, has started awarding scholarships for EU nationals only in the past two years – and just 33 UK students received an award last year. “UK numbers have room to grow,” says Hibler.

While British students aren’t known for an international perspective, costs may force them to adopt one, some educationalists believe. “I don’t think I would have been able to continue on to postgraduate study had I stayed in the UK, largely due to financial reasons,” admits Murphy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks