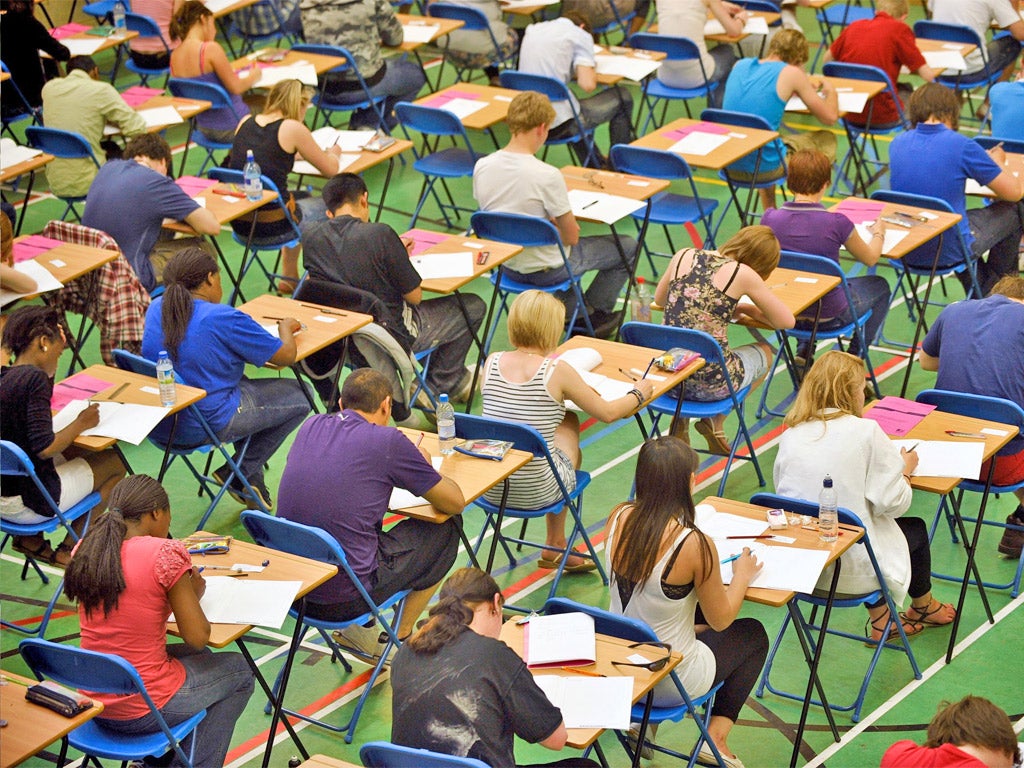

Why are so many more Firsts being awarded than ever before?

The number of students receiving first-class degrees has trebled in 15 years, far outstripping the increase in university population. Jess Denham investigates why

For recent graduates the current employment landscape could hardly seem more barren - even while grades continue to rise. Statistics released by latest reports from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that one in six students leave university with a first class degree, while two thirds achieve either a first or an upper second. The class of 2012 were awarded 61,605 firsts, three times the 20,700 that were awarded in 1999. So is grade inflation to blame, or has the calibre of students and their lecturers simply increased?

The rise in firsts, despite what immediate responses may suggest, is unlikely to be a mere, straightforward case of universities ‘dumbing down’. Bigger issues in British society are at the core, with our dire economic climate a strong possible factor. With high tuition fees and a tough graduate job market, monetary elements have exploded into play as students’ fear of the working world drives them to ditch the pub for the library more often than they may have done previously. Yet they are demanding better degrees in return, placing pressure on institutions to mark up work at the expense of academic integrity. The primary relationship between university and student seems to have shifted from that of teacher and learner to business and customer.

Toby, 22, graduated from Durham in 2012 with a first in Physics and now works in the city. He said, “Students know how well they need to do to secure a first, there is no limit on how many people can achieve one as there was in our parents’ day, and access to past papers makes it much easier to gauge roughly what you need to know. Universities are being far more generous with their marking as students have come to view higher education as a pricey investment and would not take a course where 10 per cent failed.”

A plethora of online businesses offering tailor-made essays for students to download and pass off as their own has raised speculation over the validity of coursework-based assessment, a method fast replacing exams particularly in newer universities. Many tutors offer students the opportunity to read feedback on a ‘first draft’ of coursework, enabling them to improve it before submission and sparking accusations of ‘spoon-feeding’.

However, similar criticism could be targeted at examination methods. In scientific and mathematical-based subjects, questions are designed under strict guidelines. A twenty mark question tends to have eight ‘easy marks’ that everyone ‘should’ achieve to ensure a pass, a few more are offered for fairly manageable textbook work, and then further points for ‘unseen work’ test the application of real knowledge to solve problems, splitting off students deserving of a top degree. Many would argue that instead of just serving as a means to separate first class from second, all questions should be formulated to thoroughly examine people’s detailed understanding of their subject.

Others argue that even if coursework has fuelled grade inflation, it remains a more apt assessment method than traditional exams. Dane, 23, graduated from Roehampton in 2011 with a 2:1 in Creative Writing. Now working as a social media executive, he said: “When you’re relying on exams, the people who cope best under pressure and can store the most short-term information will achieve the best results. Move the focus to coursework and the people who can truly grasp the subject material and sustain effort across a prolonged period of time are going to do better.

“My course had no exams because, as a writing course, the best way to measure it is through assignments. This meant that the final semester of each year was completely blank. Removing exams and replacing them with coursework could help people cope with increased tuition fees as a course that previously took three years could take two.”

Many universities are placing a greater emphasis on using online resources, so that students can work effectively from home on laptops. Some lecturers even use video chat platforms such as Skype and Google+ Hangout to communicate with their students, making learning from your bedroom a viable possibility and encouraging study as a result.

Oxford University proudly retains its traditional standards. A spokesperson commented, “In 2001 the proportion of final year undergraduates gaining first class degrees was around 22 per cent, while in 2011 it was 29 per cent. This compares to reports that nationally the number of first class degrees being awarded has more than doubled. The range of courses Oxford offers has remained the same apart from a handful of courses, and the assessment system continues to be based on final year examinations.”

Bahram Bekhradnia, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute in Oxford said:

"We do not know why more students have been getting firsts. It could be that they are working harder or it could be that they are better taught than in the past. It could be that as the nature of assessment has changed with a greater emphasis on coursework and less on a single summative exam, it has allowed harder working students to do better. Or it could be that marking is less rigorous. I suspect it is probably a combination of these factors."

Universities with the right to award degrees hold the power over their own courses, teaching styles, assessment and classification in a situation widely deemed unfair. Standards are internally controlled and only thinly moderated by external examiners, some of whom give the benefit of doubt to candidates on the cusp of a higher degree. A spokesperson for the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, said, “Higher education institutions are responsible for ensuring that policies- including those that guide grading and award classification- are fair. Our review teams check how they meet their responsibilities, but do not second-guess decisions made about the achievements of individual students”.

While the reasons behind grade inflation are still under investigation, it remains clear that reform is needed. Nicola Dandridge, Chief Executive of Universities UK, has branded the current awards system “a blunt instrument” that fails to provide a detailed report of what students actually achieve at university. Plans to implement a Higher Education Achievement Report (HEAR) hope to provide employers with a well-rounded, accurate impression of graduates that will not merely condense them into a degree classification.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks