The little-known role Australia played in the mission to land on the moon

When disaster struck Apollo 13, the obstacles were huge, their options limited. As one of our most well known adventures played out in deep space, it was a forgotten station in the Australian outback that was tasked with bringing the crew home, writes Mick O’Hare

Fifty years ago the world was watching rapt as one of humanity’s greatest adventure stories played out. The narrative of Apollo 13 is well known. “Houston, we have a problem” and “Failure is not an option” (neither of which were actually said during the events of April 1970) became the catchphrases of possibly the greatest rescue mission ever undertaken amid a tale of enterprise and determination like no other.

Apollo 13 launched from Kennedy Space Centre en route to make the third moon landing, but 56 hours into the flight one of its oxygen tanks exploded. From that point on it became a matter of getting the three astronauts back to Earth. Alive.

The obstacles were huge – a sick crew member, oxygen leaking into space, breathable air set to run out two days before they could return, inoperative fuel cells, fading batteries, temperatures near freezing, limited water and, to cap it all off, it was possible the command module’s heat shield was damaged in the explosion. The astronauts would simply burn up as they re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere, if they even made it back at all.

That they did was down to the ingenuity of the flight directors, notably Gene Kranz, overseen by Christopher Kraft, director of the Apollo missions, and their team back at mission control in Houston, Texas, and others around the world. It was a tribute to human creativity and resourcefulness, and the intelligence and acuity of those tasked at short notice with solving every problem. The events are immortalised in the eponymous Tom Hanks movie of 1995, from which the slogan “failure is not an option” emerged. It was an apposite choice of words.

Once command module pilot Jack Swigert’s message had come through from Apollo 13 (“OK, Houston, we’ve had a problem here”) the remarkable contingency effort swung into action. The command module (which would carry the astronauts to the moon and back) was useless – its fuel depleted and its oxygen seeping into space. But the astronauts, Swigert plus mission commander Jim Lovell and lunar module pilot Fred Haise, were on their way. In space, you can’t just easily pull on the brakes and turn round.

So the key to survival was to move the astronauts from the damaged command module into the intact lunar module (the lander that would have carried two of the astronauts to the moon’s surface) and then use the latter’s engine and systems to power them all the way to the moon, harness the gravity of the moon to slingshot around the back, and return to Earth. The lunar module, of course, was never designed for such a journey, nor was it ever intended to operate independently with a dead command module attached to it. This meant firing it and occasionally correcting course to make sure they were constantly on track.

Miss the moon and they would be heading off into the void; return to Earth at the wrong angle and the spacecraft could skim off our atmosphere and miss re-entry altogether, or simply burn up as they hit it. Lovell described using the lunar module engine as like “flying with an elephant on your back”.

This much of the story is familiar, but the sudden change in plan from routine moon landing to life-saving operation meant that an unexpected group of people were about to have their moment in the sun (or moon). Technician Hamish Lindsay was sitting at his console at the Honeysuckle Creek space tracking station in the mountains 20 miles southwest of Canberra, Australia.

Honeysuckle Creek had already achieved fame as the communications centre for the Apollo 11 moon landing. Because of the angle of the Earth to the moon, when Neil Armstrong took his “one small step for a man” on 20 July 1969 the footage was broadcast to the world from Honeysuckle Creek and not from mission control in the United States as most people assumed. Honeysuckle Creek had got lucky thanks to the timing of Armstrong’s moonwalk. That day, of course, had been a celebration; all of a sudden it was now a matter of life and death.

Without communications everything would have failed and the Australian team solved that. And their input should not be underplayed, although their story doesn’t get the recognition that perhaps it should

After Apollo 11, changes in communications systems meant that Australia’s role had been diminished. However, Honeysuckle Creek and its partner station Tidbinbilla, also near Canberra, along with the tracking stations at Goldstone in California and Madrid in Spain, were deployed to support Apollo operations and keep a routine check on the spacecraft’s progress. But the damage to the command module meant that communications were going to have to be transmitted from the lunar module with its smaller antenna and weaker signal. Nasa now needed a more powerful antenna for when Apollo was tracking across the southern hemisphere and they knew that the radio observatory at Parkes in New South Wales, 300 kilometres west of Sydney, could provide it. Mission control could not risk losing contact with the astronauts, but unless the Australians could lend a hand they knew it would be extremely difficult.

In his 2001 book Tracking Apollo to the Moon, Lindsay describes a routine afternoon at Honeysuckle Creek on 13 April preparing to measure the speed and distance of Apollo 13 as it sped on its way. But mayhem ensued when oxygen tank two exploded. Lindsay heard Swigert’s message to Houston. Minutes later Honeysuckle Creek got a call from mission control in the US asking how long would it take to get Parkes up and running. The larger antenna at Parkes hadn’t been scheduled for Apollo 13, but now the radio telescope’s bigger 64-metre dish was required. Lindsay’s colleague, the deputy director of Honeysuckle Creek and ex-pat Yorkshireman Mike Dinn, pointed out that Parkes usually needed plenty of warning. He recalls telling Nasa: “It wasn’t scheduled, at which point they told me Chris Kraft would be calling my director. But we knew it was serious as soon as we heard Swigert’s message.”

A clearly rattled Kraft got on the phone. “Look, we have a major problem on the spacecraft. Do what you can to get Parkes up,” he insisted. “Never mind about money.” The Australians jumped to it. Luckily most of the equipment that was needed was still in place at Parkes so the people working at Tidbinbilla, familiar with the equipment Nasa had supplied for Apollo, hastily got on the plane and flew to Parkes. John Saxon, another ex-pat Briton who was operations supervisor at Honeysuckle Creek, adds that “Parkes had a more sensitive antenna and could track deep space more precisely”.

John Bolton was the director at Parkes. “I knew it was serious,” he recalled before his death in 1993. “We had an experiment taking place at Parkes and needed to dismantle it quickly. But fortunately that meant there were lots of engineers on site. It was a remarkable effort, transferring everything to get Parkes up and running in just a few hours. It would normally have taken days.”

Although Parkes would be more effective at receiving Apollo’s weakened radio signals, Honeysuckle Creek was still the link with mission control in Houston. “All messages and information Parkes received from Apollo had to be relayed first to Honeysuckle Creek for processing and then onto Houston,” explains Saxon. Not only that, but Parkes was having difficulty actually locating Apollo. “The signal was weak,” says Bruce Window, one of the supervisors flown in from Tidbinbilla. “And we were just relying on predictions of where the spacecraft should be. It was difficult and then, when we finally picked up the broadcast, the link to Honeysuckle had not yet been activated. I had a telemetry cable in my hand that I was feeding into an ordinary phone line and I was shouting with frustration as I couldn’t get the link to work,” he told honeysucklecreek.net in 2011.

“At first we were forced to use a standard phone line,” says Dinn, “although it was of poor quality.” But another difficulty soon became apparent. Nasa had intended for a used section of the Saturn V rocket (the spent third stage known as S-IVB) that had launched Apollo on its way to follow the spacecraft to the moon and for it to crash-land, creating seismic waves for geologists to study the interior structure of the moon. The lunar module would normally not have been in action at this stage of the mission but it was now occupied by the three astronauts using it as a lifeboat to get home and it was transmitting at the same frequency as the S-IVB. It had not been planned for both to be in operation at the same time. And it was making it very difficult for ground crews to communicate with the astronauts and vice versa.

At this point Dinn and his operatives at Honeysuckle Creek stepped up. Dinn had realised before the mission that if the lunar module was fired up, its signal would interfere with that of the S-IVB. It was prescient. He had previously been involved in planning for two unmanned spacecraft to be on the moon at the same time, both transmitting on the same frequency and what would happen in such a situation. So although the scenario was different, the solution was the same.

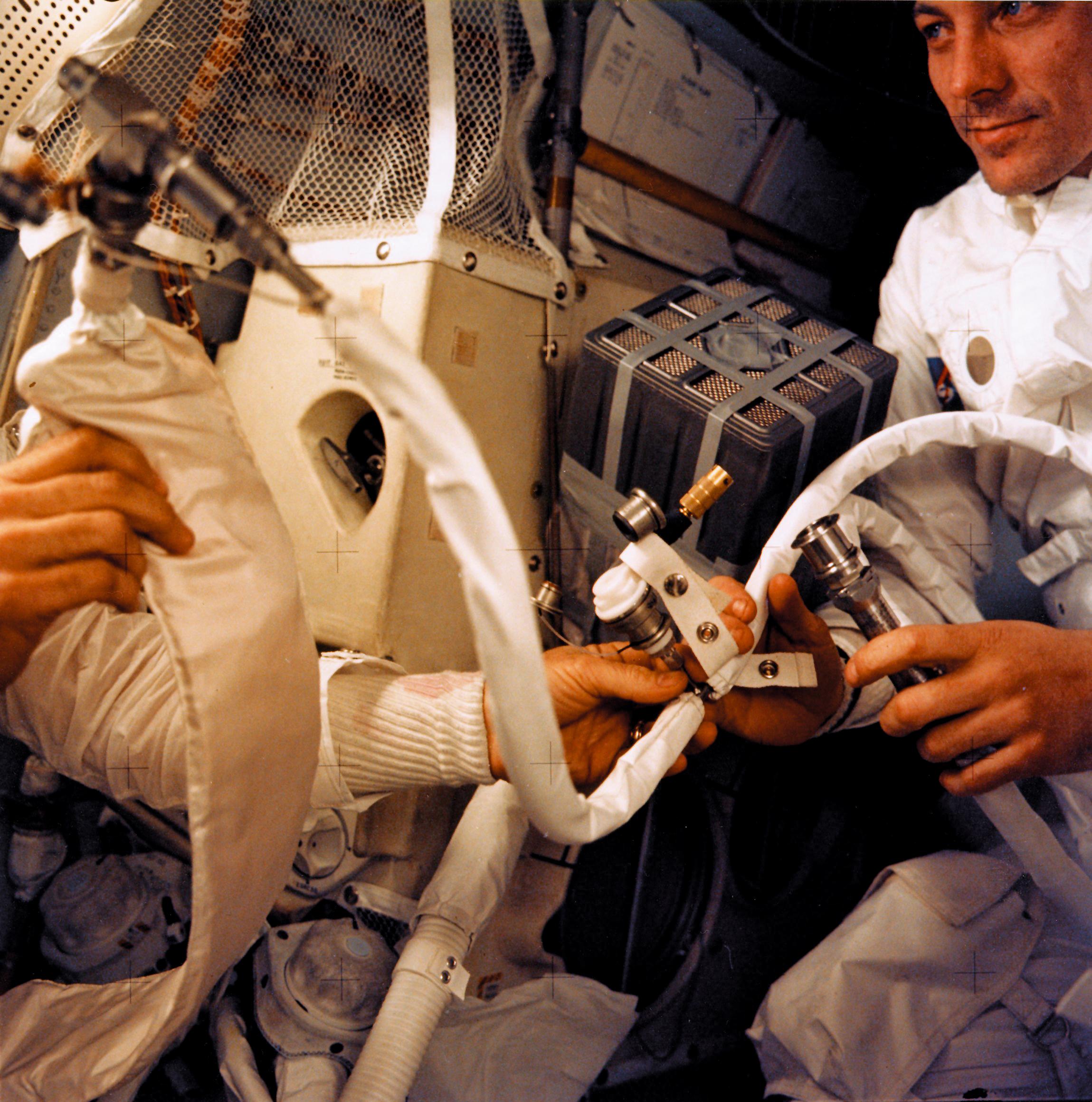

John Mitchell, one of Dinn’s supervisors, arrived at the same plan independently. He figured out that if the lunar module could switch off its signal so that that the S-IVB signal could be isolated, then when the lunar module switched back on the two signals would be separate. Dinn passed on the plan to Houston. “I asked them to turn off the lunar module for five minutes while we isolated the S-IVB signal,” says Dinn. At first, mission control was sceptical and instructed Australia to attempt another fix. The Aussie operatives at Honeysuckle Creek were certain this wouldn’t work. In fact they told Houston that it could wipe out telemetry as well as voice contact. And it did.

So much had to come together to ensure Apollo 13 came home. And it was the sheer will and team effort of people pulling together to find a solution to everything

It was a critical juncture. If the astronauts could not be contacted then the alterations they needed to make to their systems, the changes required to their air filters and the course corrections they had to make could not be given to them. It was a fraught moment and transcriptions of the discussions between Australia and the US highlight the professionally reasoned but often stressful situation the teams were in. Dinn proposed the solution to the Americans again. This time they had no option but to listen to their colleagues in Canberra. After an hour checking the proposals they gave the go-ahead to both the Honeysuckle Creek and Goldstone stations.

But there was one more problem: no one knew if the messages were getting through to the astronauts. If they weren’t, Apollo 13 was likely to continue on its way, unable to receive instructions from Earth – and most likely miss its return orbit around the moon. A message was sent out to the astronauts. Tense moments passed, and then the radio link from the spacecraft vanished. Lovell and his crew had received the instruction. “At that point we were able to tune the S-IVB away,” says Mitchell in Tracking Apollo to the Moon. “Once the lunar module switched back on everything worked fine.”

It was a fair dinkum, all-Aussie fix. The Australian comms link continued to operate all the way to the moon and back. Later that day Kraft told the world’s media that “this is as serious a situation as we have ever had in a manned spaceflight”. It was, but now, thanks to Honeysuckle Creek, he had the reassurance that he could at least speak to the men in peril. While the ingenuity and inventiveness of the minds back at Nasa played their now famous role in the return of Apollo 13 it would not have been possible without the equally fine minds in the southern hemisphere. “All our staff were vital to the success,” says Dinn. “It was an age of analogue equipment and the skills of the operators came to the fore.”

Apollo 13 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on 17 April. And still Honeysuckle Creek played a key role. It was the last station to track the command module before splashdown, and accurate readings were required because of the change in mission plans. The station also had to note where the lunar module – which would normally have been left on the moon’s surface but also entered the Earth’s atmosphere after ferrying the astronauts back home – came down. It had been carrying radioactive material and Nasa was afraid it might come down over land. In the end it crashed into the Tasman Sea.

There was recognition in the Australian parliament when senator Ken Anderson reported the efforts of his compatriots to the nation, while Dale Call, the network director of Nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, offered his personal thanks “for the outstanding support provided by Honeysuckle … which contributed to the safe return of the Apollo 13 crew”. And praise also came from the very top.

US president Richard Nixon sent a personal letter to Australian prime minister John Gorton offering “the people of Australia my deep appreciation for your nations’ assistance”. He conveyed his “personal thanks to all of your people who worked so hard to maintain our communications with the weakened spacecraft as it returned to Earth”. Kraft would later describe Australia’s role as “unique and critical”. And, of perhaps greater reward to the people working at Honeysuckle Creek, Swigert visited them personally the month after he returned from space to offer his thanks.

“So much had to come together to ensure Apollo 13 came home,” says Doug Millard, senior space curator at London’s Science Museum. “And it was the sheer will and team effort of people pulling together to find a solution to everything. But without communications everything would have failed and the Australian team solved that. And their input should not be underplayed, although their story doesn’t get the recognition that perhaps it should.”

And what of Honeysuckle Creek now? The station closed in 1981 as its importance to the space programme diminished. All that remains is its concrete foundation, although its decommissioned antenna is now at Tidbinbilla where the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics has declared it a Historic Aerospace Site. Today anybody visiting would have little inkling of its major role in the Apollo programme that took humans to the moon (or not). Perhaps, considering space is the most remote and hostile outback ever visited by humans, it’s no wonder Apollo 13 needed a bunch of blokes from the back of Bourke to keep it on track.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks