Are you dead? Morbid app offers solution to the worst outcome of the loneliness epidemic

After witnessing first-hand the tragic consequences of extreme social isolation, which led to a neighbour dying eight years before he was found, Anthony Cuthbertson looks at how technology is offering a small fix to a problem it helped create

Content warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of death that some readers may find disturbing.

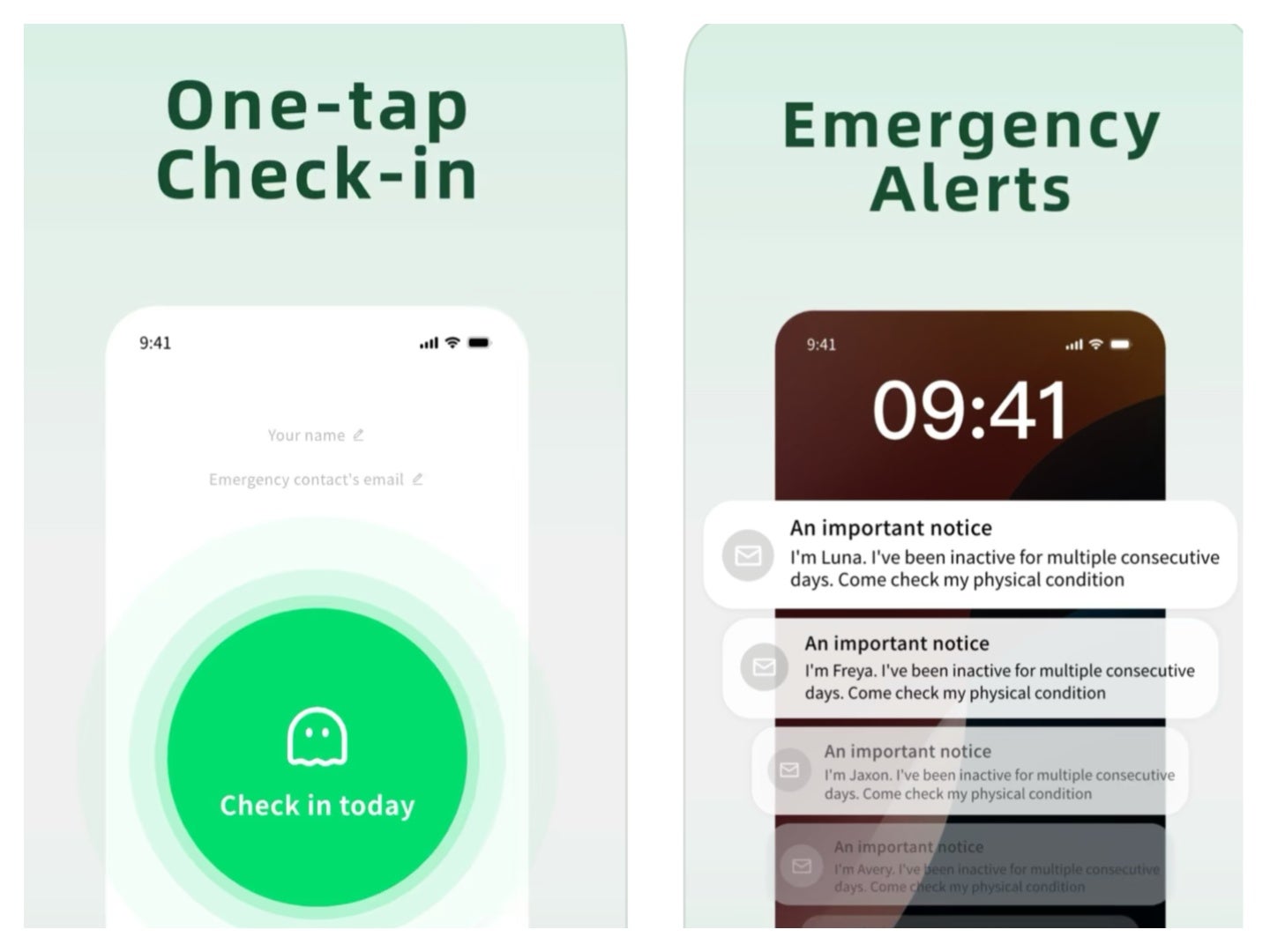

Every two days, you have to push a green button to confirm that you are alive. If you don’t, it triggers an automatic email alert to your appointed emergency contact, informing them of your potential demise. “I’ve been inactive for multiple consecutive days,” the email warns. “Come check my physical condition.”

This is the concept of the Are You Dead? app, which is currently the most downloaded paid app in China. Its popularity is fuelled by a widely reported loneliness epidemic in the country, with projections suggesting there will be 200 million one-person households by 2030.

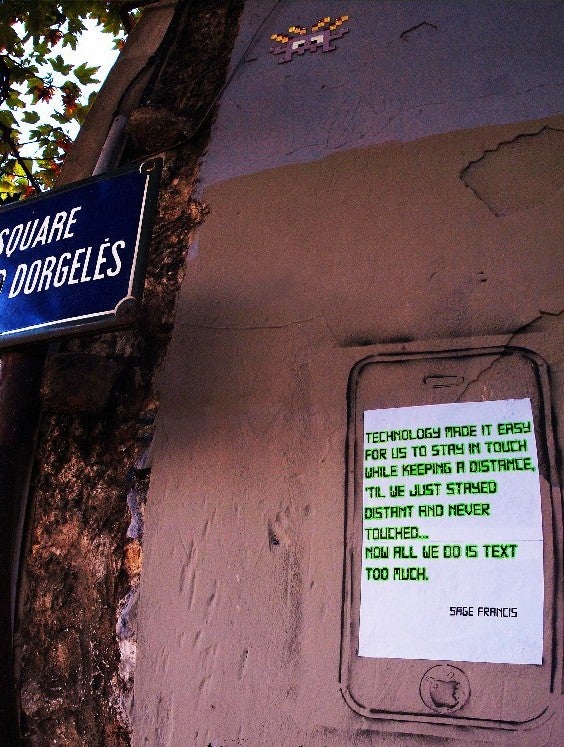

Social isolation is something that has been increasingly studied globally since the 2010s, with researchers pointing to technology and social media as being among the leading factors of reduced real-life relationships. But it is through technology that the makers of the Are You Dead? app are seeking to find some sort of a solution. And it is an app that I wish had been created sooner.

In 2011, I was living on the edge of Paris with my girlfriend and two kittens when tiny flies began to appear in our flat. The cats would chase and trap and eat them, which was funny at first, but we soon began to worry that the clattering of claws on the wooden floorboards was disturbing our neighbours downstairs. So we bought a rug to soften the sound, and some spray to kill the flies – but they kept returning.

Our apartment was on the sixth floor of a building with no lift, meaning I would pass the door of the person living directly below us every time I left or returned home. On one of these trips, I noticed a letter sticking out of their doorframe that EDF had left after coming to read the electricity meter. It remained there for weeks, presumably meaning the occupant was on holiday, or not living there any more. Good, I thought, no one to complain about the noise.

More weeks went by, the flies grew worse, and a strange smell began to fill the top two floors. Naively, we thought it must be rotting rubbish from our absent neighbour. The letter wedged in their door was joined by unpaid EDF bills.

Early one Saturday morning, there was a banging at our door. It was the first time anyone had ever knocked on our door in the eight months we’d been living there, and when I opened it, a policeman was standing there. He asked when the last time we had seen our downstairs neighbour. We never had. He’s dead, the policeman said bluntly. And he had been for a very long time – probably since before we moved in.

The French capital is one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, but this was apparently not a particularly rare case, according to the police. It was, however, an unusually grim one. Our neighbour had decomposed so deeply into his sofa that parts had seeped into the floorboards below and caused a stench that permeated the walls and ceiling. The place was infested with maggots and flies, and even after an extensive clean-up operation by people in hazmat suits, the top few floors of the building continued to smell for months. It was tragic and revolting.

At least 40 people lived in our building, and no one had noticed that our neighbour had died. It was an indictment of modern city living, and one of countless deaths that happen across Paris and other big cities every year. In 2023, a man’s mummified corpse was discovered in a flat that people had presumed empty. He had died by suicide eight years earlier.

There are no official statistics, but such cases of mort solitaire, as they are known in France, are so commonplace that several non-profits have been set up in an attempt to prevent them. Voisins Solidaire is one initiative aiming to create and strengthen neighbourhood solidarity, and has already developed a network of 150,000 volunteers who offer support and company to the socially isolated.

Dr Vivek Murthy, the former surgeon general of the United States, has described loneliness as a “defining challenge of our time”, attributing it to an increased risk of stroke, heart disease, diabetes, cognitive decline, depression and premature death. Last year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released a report that linked 871,000 deaths annually to loneliness – an estimated 100 deaths every hour. One in six people globally is affected by loneliness, according to the report, despite technology offering more ways to keep in touch than ever before.

“Even in a digitally connected world, many young people feel alone,” said Chido Mpemba, who co-chaired the WHO commission behind the report. “As technology reshapes our lives, we must ensure it strengthens – not weakens – human connection.”

The advent of generative artificial intelligence and the growing trend of AI partners and friends, combined with increased urbanisation and an ageing population, may well accelerate the phenomenon. It will take more than an app to fix this social fragmentation, but it could help avoid the worst outcomes.

It is something the founders of the Are You Dead? app appear well aware of, noting in a post over the weekend: “We would like to call on more people to pay attention to the elderly who are living at home, to give them more care and understanding. They have dreams, strive to live, and deserve to be seen, respected and protected.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks