At last, the web goes truly worldwide

For 40 years, the Latin alphabet has been the sine qua non of the internet. Jack Riley and Larry Ryan report on a linguistic revolution in cyberspace

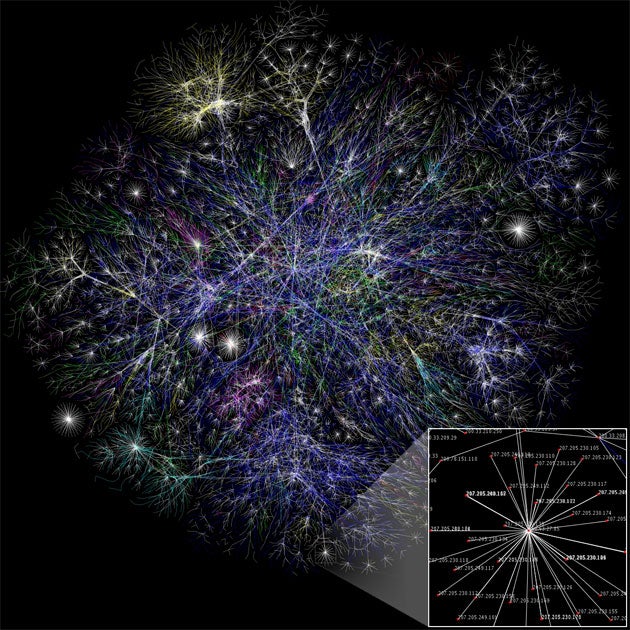

Considering it is known as the "World Wide Web", the internet's reliance on the English language has long been maligned as a hangover from the web's beginnings as a communications tool for the US military.

Yesterday, this dominance was shaken for the first time in 40 years, with the announcement by the internet regulator Icann (the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) that other languages will now be afforded the same online status as English. The Mandarin and Cyrillic alphabets will be the first to be added.

In the appropriately hi-tech South Korean capital of Seoul, the body's chief executive, Rod Beckstrom, announced moves to allow internet domain names (the end of web addresses – .com, .co.uk, etc) to be registered in languages using characters other than the 26 of the Latin alphabet. Heralding the changes as the "internationalisation of the internet", Mr Beckstrom was in grandiose mood. He added: "This represents one small step for Icann, but one big step for half of mankind."

As a result, internet users will be able to enter entire web addresses in their native language for the first time: 100,000 new characters are expected to be added in a multitude of languages including Mandarin, Russian and Hebrew.

The fast-track application for the registration of new languages will open on 16 November, with the first successful applications expected to be adopted by the middle of next year.

The move is just the latest step in a decentralisation of control over the web, hot on the heels of the decision four weeks ago to abandon the periodical reviews by the US government, which many believed helped keep the organisation firmly under the watchful eye of the American establishment.

Ever since the creation of Icann 11 years ago, there have been growing concerns over the sway American administrations have had over the internet, with groups such as W3C, the organisation that oversees the web's continued development, campaigning for greater openness in internet naming conventions to improve global online access.

"Making the World Wide Web really worldwide has long been an aim of ours," said W3C's Richard Ishida.

The development comes at a time that sees America's economic power around the world diminishing. With Chinese web users now outnumbering their American counterparts, commentators will see this change as another step in the gradual de-Americanisation of the internet.

Many brands that are currently considered globally dominant by the West are still struggling to control the market in countries like China and Russia. Google, for example, has a 71 per cent share of the search market in the US, but garners just 31 per cent of online queries in China, where homegrown competitor Baidu has a 63.9 per cent share.

Icann's revised status as an impartial international body is also a concession by its American staff that the US can no longer play a unilateral role in mediating the development of the internet.

It will hope that by offering greater representation to countries from emerging Asian economies like China, South Korea and India, the role of the West can be scaled back without the kind of tumultuous disagreements threatened by those who have long lobbied for the US's role to be cut back. Mr Beckstrom said of the growing influence of Asian governments, technology companies and audiences: "The first countries that participate will not only be providing valuable information of the operation of IDNs in the domain name system. They are also going to help to bring the first of billions more people online – people who never use Roman characters in their daily lives."

For British internet users, one potential impact is the possibility of an upsurge in the number of virus and "phishing" sites (which try to steal sensitive information like identities or bank details) following the registration of these new domains using the multiple alphabets.

Despite recent guidelines from organisations seeking to stem the proliferation of scam websites, representatives from anti-virus companies yesterday expressed concern at the new avenues of opportunity for internet criminals.

"This is a pivotal point," said Tony Osborn, of internet security firm Symantec. "There will be far more sites that you cannot trust. With any new technology we have to rise to those challenges. There will be a period of time where we need to understand the dangers."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks