Could the UK Government shut down the web?

A huge cyber attack or mass civil unrest would give Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt powers to shut down the web. But how is it even possible? Nick Harding finds out

According to David Eagleman, a respected scientist and the author of Why the Net Matters, 21st-century technology obviates the causes that led past civilisations to collapse and because of this, he argues, that the web is crucial to our survival.

It has become such an intermeshed part of society that a world in which the internet suddenly goes down or is switched off is hard to imagine. The Hollywood-sized scenario reads like this: email, telephone and television services would go dark, media organisations become unable to gather and disseminate news, governments struggle to communicate emergency information, commerce grinds to a halt, shops run out of food, the transport system collapses and electricity supplies are be severely disrupted. Within months gangs of feral youths would take over the towns, cannibalising the weak and elderly, while citizens trembled behind barricaded doors, weeping over their useless copies of Call of Duty: Black Ops.

In Britain there are two pieces of legislation which give the Government power to order the suspension of the internet and, in theory, bring about web armageddon. The Civil Contingencies Act and the 2003 Communications Act can both be used to suspend internet services, either by ordering internet service providers (ISPs) to shut down their operations or by closing internet exchanges. Under the protocol of the Communications Act, the switch-flicking would be done by the Culture Secretary. In the eyes of the legislature, Jeremy Hunt is the man invested with the power to send us back to the dark ages.

The chances of this happening are extremely remote, partly because these powers can be used only in times of emergency to protect the public and safeguard national security and partly because consensus governance would act as a check to any nefarious individual ambitions. In theory, the mechanical process of shutting down the internet should be simple. In addition to ordering the nation's main ISPs to cease operation, officials can also close main internet exchanges such as Linx – the London Internet Exchange –which handles 80 per cent of our internet traffic.

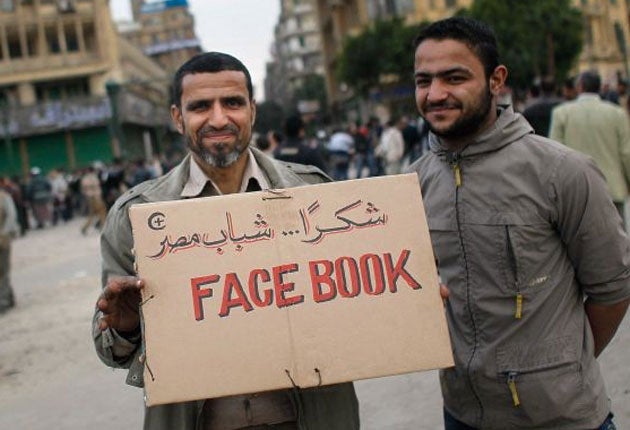

The ISP shutdown process was used recently by the Hosni Mubarak's government in Egypt, ostensibly to stifle the propagation of dissent. On 27 January Egypt was effectively disconnected from the rest of the web after its ISPs were ordered to shut down their services. Shorty after going offline Vodafone Egypt issued a statement explaining: "Under Egyptian legislation the authorities have the right to issue such an order and we are obliged to comply with it."

Egypt's other three big ISPs – Link Egypt, Telecom Egypt and Etisalat Misr – also stopped services. A few days later the final service provider, Noor, went down, taking the country's stock exchange with it.

The pattern has since been repeated in other parts of the Middle East where popular uprisings have occurred. On 19 February Libya went completely offline. In Bahrain reduced web traffic flow was reported between 14 and 16 February.

As the authorities in Egypt discovered, however, the net kill-switch can be circumvented. During the shutdown there, telephone lines remained active and tech-savvy protesters were able to set up information networks using dial-up modems.

Telecomix New Agency, a global affiliation of internet activists, reported: "We set up servers which could answer modem calls via landline. Many of the Telecomix agents who were setting up these systems were not even born when this technology was considered modern. Some touched their first modem in those days. There were no instructions how to set up a computer to make a modem call and connect it to the internet. We had to learn how to do it. Outside Egypt, in France, the Netherlands and Germany, some providers reactivated their modem pools."

Because modems work by dialling a number and swapping data through a telephone line, lists of active dial-up ISP telephone numbers had to be distributed by fax and by hand because email services had been taken down along with domestic internet services. Numbers were also read out over shortwave radio. Even normally apolitical companies made efforts to maintain the flow of information. Twitter teamed up with Google and its newly acquired SayNow company and offered an internet-free way of Tweeting over the phone. Callers could leave voice messages including #tags and their messages were posted online for them.

That repressive governments have been able to use laws similar to those in the UK to implement such draconian crackdowns on the freedom of their citizens has rightly raised questions about whether our politicians have too much power over the internet.

From a legal standpoint, there are safeguards. The section of the Communications Act which allows internet provision to be suspended can be enacted only "to protect the public from any threat to public safety or public health, or in the interests of national security". And there are statutory avenues for recourse should these powers be abused.

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport explains: "It would have to be a very serious threat for these powers to be used, something like a major cyber attack. The powers are subject to review and if it was used inappropriately there could be an appeal to the competitions appeal tribunal. Any decision to use them would have to comply with public law and the Human Rights Act."

Experts such as Dr Peter Gradwell, managing director of business internet provider Gradwell and trustee of the Nominet Trust, believe the fail-safes are adequate.

He says: "The legislation also includes the requirement to make compensatory payments for loss or damage. Would the Government want to foot the bill for switching off a multi- billion-pound industry? If a notice is served on an ISP and ignored, the penalty is only a fine. If the public were massing on the streets of London, I believe that many internet providers would be happy to argue the legitimacy of such a penalty in court."

As long as the balance between freedom of information and protection of the public is maintained, few may argue against having what amounts to a national firewall at a time when cyber warfare is arguably the fastest growing threat to national security.

In the US lawmakers are drafting even more wide-ranging legislation than that available to politicians in Britain. The Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act will give President Barack Obama the ability to declare a state of cyber-security emergency, during which he would have full control over internet networks and could isolate the country and its critical national infrastructure from attack for a period of 120 days.

However, if an eventuality ever arises in which Western governments need to use these powers, they may ultimately prove useless, according to many specialists. While Egypt was relatively simple to switch off, the UK, with its advanced digital infrastructure, would be much harder. It has more than 3,000 independent ISPs, several national mobile operators and at least 10 undersea high-speed fibre cables linking it to all other parts of the world – mainland Europe, Africa and the Americas. Each of these cables is capable of carrying huge amounts of traffic.

If, for example, the Coalition invoked the Civil Contingencies Act and shut down the main exchanges, some mobile broadband operators would still be able to operate. T-Mobile could route traffic via Germany and O2 through Spain. Some dial-up services such as SprintNet, which is used for AOL facilities, could still operate, because its services are routed through the United States.

As Claire Sellick, event director of Infosecurity Europe, explains: "On a practical level, switching off the internet in the UK would be very difficult. Most ISPs have diverse routing, with some – notably mobile broadband operators – routing traffic overseas. It would only be partially effective. Broadband local delivery may be curtailed but dial-up modem, leased line and other access systems would still operate."

The problem comes down to the very nature of the internet in developed countries. It is a mesh of networks. It transcends borders and has no definable beginning or end. As a result of this structure it is almost impossible to isolate all the connections. In the UK, many providers have private interconnections with each other and with other providers in other nations as well as connections to internet exchanges.

In addition the UK also has a diverse alternative infrastructure which could be utilised to carry data. Many cities have wireless and wimax mesh networks in place, there are lots of radio enthusiasts and privately owned optic fibre follows roads, railways, waterways and underground networks.

As Dr Gladwell explains: "Any shutdown would be hugely problematic to start with, but could be easily subverted. If you take down something like Linx it would initially affect lots of people but you would end up with a secondary network being built up quite quickly."

It seems highly likely then, that as happened in Egypt, if the Jeremy Hunt Doomsday scenario were ever come to pass, an alternative network would quickly expand and provide access to the internet for all. Which is a relief.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks