Driverless cars could offer governments new forms of control

Autonomous vehicles are set to enable new forms of surveillance and oppression

Imagine a state-of-the-art driverless car zipping along a road with a disabled, 90-year-old passenger. A young mother with a toddler steps onto the road. The car must make a decision: drive into the mother and child and kill them, or swerve into a wall and kill the passenger.

This is a variation of the trolley problem, a thought experiment which dominates academic and popular thinking about the ethics of driverless cars. The problem is that such debates not only dismiss the complexity of the system in which driverless cars will exist, but are also moral red herrings.

The real ethical issues lie in the politics and power concerns with driverless cars.

Governments across the world are taking a deep interest in driverless cars: the German government has produced ethical guidelines for driverless cars, the UK government has promised driverless cars to be on the road by 2021, and the Russian government by the end of 2018. China also has ambitious plans to connect driverless cars to the internet and install sensors in roads and traffic lights by 2025.

Most revealing is the way driverless cars feature in the EU’s White Paper on the Future of Europe, published in March 2017. They form a telling part of a snapshot of how Europe might look in 2025; a future where EU countries have effectively joined to become one federal superstate.

In this scenario, the White Paper says that driverless cars will flourish, flitting unhindered across borders, from city to city.

There’s a reason why governments are so keen on driverless cars – and it’s not just because of the potential economic benefits. They also offer the chance for even greater tracking and greater control of every citizens' whereabouts.

Far from setting us free, driverless cars threaten to help enable new forms of surveillance and oppression.

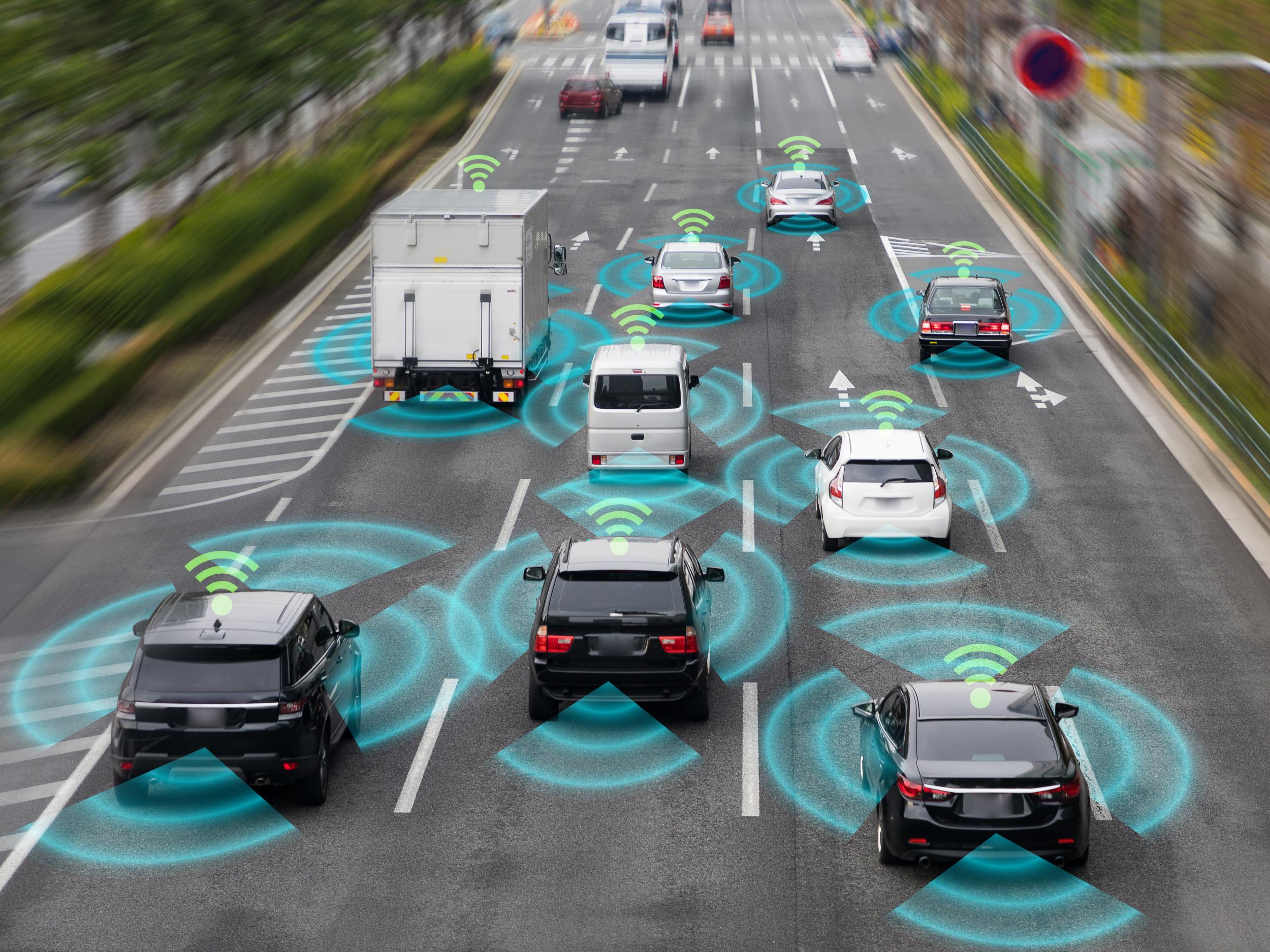

A driverless car is a computer on wheels, the ultimate internet-connected mobile device. Bristling with sensors, it provides a constant two-way flow of information. The car sends information about its performance to the manufacturer.

It receives software updates and control signals about adjustments to its behaviour. The manufacturer, in turn, knows where the car is, what the road conditions and temperatures are, and how the vehicle is performing at a particular speed.

The car’s insurer may receive minute-by-minute information about the vehicles' state, location, speed and the condition of the road it’s on, to vary the insurance accordingly. It could even give a ten minute warning of loss of cover and halt the car.

Meanwhile, government databases will also be likely to know where the car is, whether it is meant to be there and where it’s going – and even, using predictive analytics, where it will go for its next journey.

Smart motorways will manage flows of traffic, slowing down driverless cars as part of a stream of communication between the car and the road. In smart cities, traffic lights will reroute cars into detours according to calculations and predictions on traffic jams, road works, or state requirements.

Markets in fast routes through cities and to central destinations may also be created. Companies may pay for employees to use priority virtual routes. Travel logs may make it quite clear where the driver has gone and when.

Reasons for your journey may be inferred predictably from the landscape, from destinations and from timing.

For more than 130 years, cars have represented ultimate autonomy, individuality and democratic freedom. Our car trips are private and anonymous. We can go where we like and when we like. We don’t have to tell anybody.

And we retain responsibility for whether we obey the law. Driverless cars will bring all of that to an end.

Now manufacturers, governments and city authorities will know where we’re going, what we’re doing and when we're doing it. If anyone doesn’t like what we’re doing, they will be able to stop us, withdraw technical and accident cover, stop us using particular roads or streets, or just shut us down completely. It won’t be the driver that’s autonomous, but the authorities and systems that run and maintain their car.

In the rhetoric of making us safer and reducing risk, power will be taken away and given to central authorities – whether they are cities, governments or commissions. Now the controllers can simply change our route for their own purposes, whether to prevent traffic jams or to clear a route for a dignitary. To render us safe, governments will leave us powerless.

In a democratic state, the growing flow of personalised information towards centralised authority will provide the basis for regulation and enforcement. Its citizens will be the target for behavioural nudges and advertising flowing into the driverless car.

In a dictatorial state, the authorities can stop you going to a demonstration, or stop you going to church.

And such centrally managed systems, which will be essential for the safety of driverless cars, are not only open to the inevitable technology failures of complex systems, but also to hacking and attacks by other states and individuals.

Why hack into one car, when you can hack into a whole city system and bring traffic to a halt, or crash 30,000 cars into each other?

In reflecting on the ethics of driverless cars, we need to move beyond the constraints of the trolley problem and look at a wider agenda that addresses concepts such as autonomy, community, transparency, identity, value and empathy.

Our ethical debate has to address the power shifts, the political responsibilities and the human rights that our vision of driverless cars may require to be sacrificed.

Neil McBride is a reader in IT management at De Montfort University. This article was originally published on TheConversation.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks