Hanging on the telephone: How did we end up with Handel tinkling down the line?

Being forced to listen to a tinny tune while we wait on hold can feel like purgatory. But who had the idea that there should be a soundtrack at all?

In 2012, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, an Adelaide man was kept on hold with the airline Qantas for 15 hours. As a recorded message affirmed, over and over, that a customer service agent would be with him "soon," he simply stayed on – working, reading, waiting. As he told the newspaper, "I wanted to find out what exactly they meant when they said they would be with me as soon as possible."

Many of us are no doubt plunged into our own philosophical inquiries into the nature of time as we wait – albeit not to such lengths – on hold. (I have found Wittgenstein's query, "Can time go on apart from events?" to be a useful starting point). Hold is the true purgatory of modern existence, a place of temporary damnation, filled not with cleansing fire but a gentle wash of music, punctuated by occasional glimpses ("your call is important to us") of the promised land.

About that music: while recently put on hold – after first enduring the "confession" ritual of pressing telephone buttons to indicate why I was calling – the sounds of Handel's Water Music came through the earpiece of my iPhone. I would not say it came "pouring" through so much as "dribbling"; monaural, faded by distance, troubled by hiccupy signal dropouts.

As I listened, I became aware of the oddity of the situation: Water Music is a work executed by a German-born, England-adopted composer – described by Christopher Hogwood as "difficult, unusual, over-interested in food, independent, larger than life in all sense and short-tempered with it" – for a politically important "water party" on the river Thames in the summer of 1717. (Notes Hogwood: "Handel was writing pure entertainment music – music on the water rather than about water.")

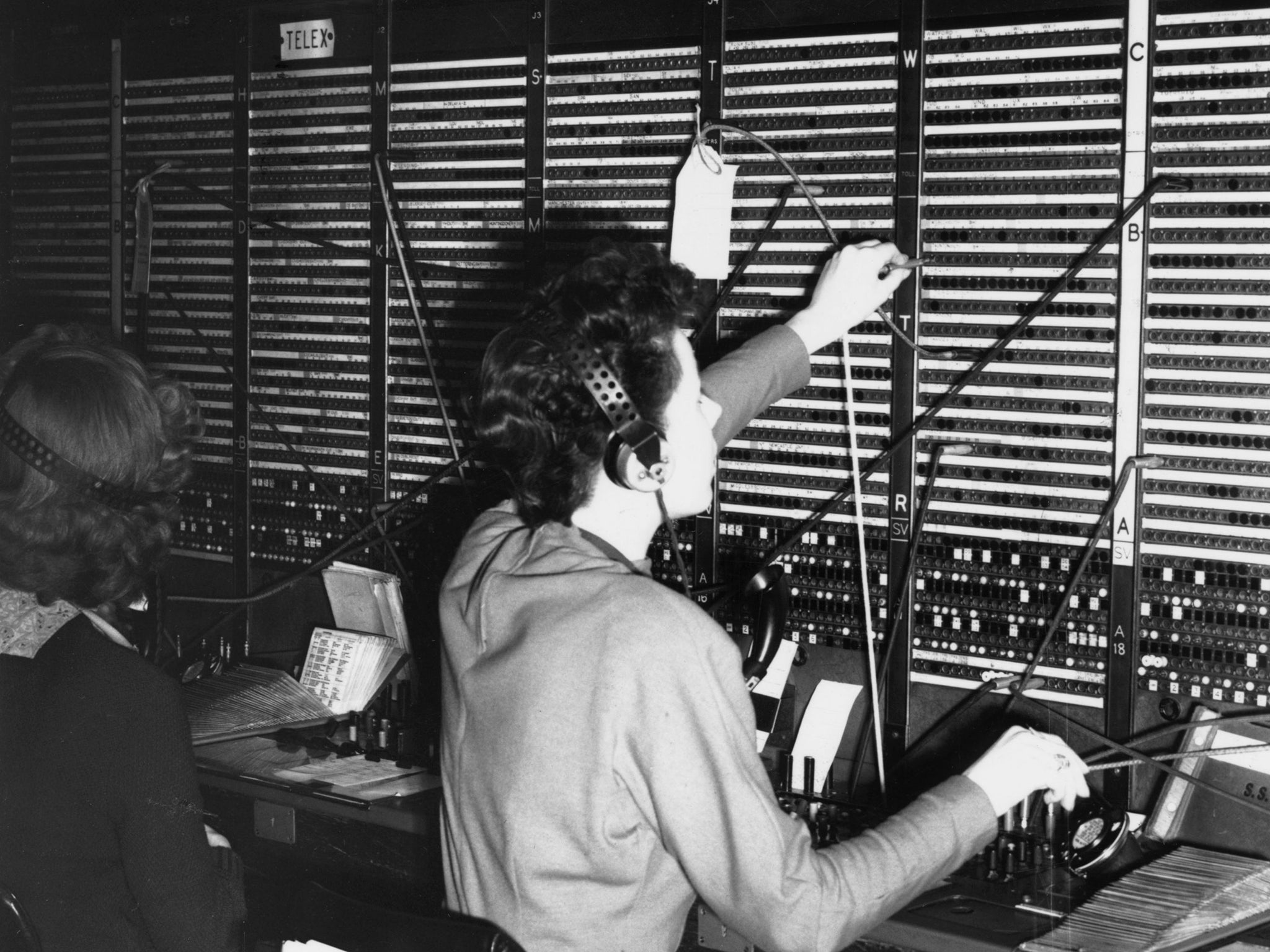

How strange that this 18th-century riverboat dance music should now provide the sonic backdrop to the eventual fulfillment of a 21st-century customer service experience. Handel had written tafelmusik – literally, "table music," for guests at table – but could he have known he was also writing telefonmusik? But then I wondered: Who had the idea that there should be a soundtrack at all? Perhaps surprisingly, given that select late 19th-century audiences in Europe had actually received live opera broadcasts via telephone, the idea of hold music doesn't seem to appear until fairly late in the 20th century.

What we may now forget is that, in the early days, one stayed "on hold" simply to make the call. It probably seemed a small price to pay. Writing about the first transatlantic telephone call from New York to Paris, in 1928, The New York Times described the dizzy experience: "For those who speak for the first time there is no thrill comparable to that which comes with the first signal. 'Your New York call is coming through.' Hold the line. Wait a minute. That minute is a thing of very mixed emotions. One feels that something memorable should be spoken and can think of nothing to say."

Presumably, those emotions became less mixed as the telephone became more familiar, and the person placed too long on hold would have plenty to say. "Wasted, wasted minutes that couldn't be worse," go the opening lines Elizabeth Bishop's 'While Someone Telephones', "Minutes of a barbaric condescension". But there was a more elemental problem with the "silent hold" – there was no way to know if one was still actually "on the line."

But in the spring of 1962, an application appeared in the US Patent Office, humbly entitled "Telephone Hold Program System". "In the course of receiving telephone calls," it began, a bit grandly, before settling into the problem at hand: what to do about that dead silence the caller endured while calls were transferred, their respective parties chased down? Operators were supposed to check in again on callers who had been waiting; but what if they got busy? "In any event," the application went on, "listening to a completely unresponsive instrument is tedious and calls often are abandoned altogether or remade which leads to annoyance and a waste of time and money."

The solution? "It is an object of the present invention to provide a system of the character described which upon actuation of a hold instrumentality, eg, a key or button, will connect the incoming call to a source of programme material, eg, music, thereby to pacify the originator of the call if the delay becomes unduly long, and also to while away the idle time of the caller who is awaiting connection to a certain party or extension."

The patent's filer was a factory owner named Alfred Levy, who, by one account, discovered that, by dint of a loose wire touching a steel girder, his company's telephone system was picking up broadcasts from the neighbouring radio station. When callers were placed on hold, they no longer heard silence, but… music. The world of "music on hold" was born. Eventually, a rival to music arrived – so-called "messaging on hold." Why simply play canned music to listeners when you could promote your business? In the mid-1980s, companies began mixing music with messages; companies such as American Telephone Tapes crafted "sultry voice" announcers who would break into the music "every 40 seconds or so".

Today, it is taken as an article of faith that "silent hold" is commercial death (you probably cannot remember the last time you had a telephone wait unaccompanied by something). Hazily sourced statistics blare from the websites of hold-message companies: "70 per cent of callers put on silent hold will hang up within one minute!" The industry is these days so established that its trade group (the On-Hold Message Association) even has its own award show (last year's winner was a Canadian commercial cleaning company).

Apart from the original intention of signalling that one is still on an active line, the growth of music and messaging on hold was driven by a simple construct of human psychology: the "resource allocation model." As the Journal of Retailing puts it: "Music reduces the negative effects of waiting because it distracts attention from the passage of time, and, as a result, consumers perceive the length of the wait to be shorter than that when there is no music."

The less you pay attention to time, the faster it seems to go. The longer one feels one has waited, the thinking further goes, the lower one's satisfaction with the experience.

And, generally, research has supported the axiom that, when it comes to waiting on the phone, something is better than nothing. A 1997 study in the Journal of Direct Marketing, for instance, found that callers to a fictitious business reported shorter waits (and higher customer satisfaction) when they heard a range of hold music – from Steve Winwood to Handel's Water Music (!) – than when they heard silence.

But, of course, it's not so simple. What happens, for example, if you hear music you don't like? A 1990 study in the Journal of Services Marketing, for example, found that younger people reported their shopping time to be shorter when it was accompanied by Top 40 music; that equation, however, reversed itself for shoppers over 25. And yet music that you like poses another problem, as identified by a study by Nicole Bailey and Charles Areni. "Compared to more anonymous selections," they write, "familiar music is more accessible in memory; hence, more events are associated with the target interval, which expands perceived duration." Of course, even anonymous hold music can go on to become familiar, almost loved – in the famous case of Tim Carleton's "Opus No 1" for the telephone company Cisco, a synth track he recorded in his garage as a teenager that has become the default music for call centres across the world.

Then there are questions of valence. Does the sort of generally happy, upbeat music one hears on hold make waits shorter? A study in Acta Psychologica found that happy or sad music, while it might influence emotion, seems to do little to time (though common sense dictates that if you are going to make people wait, you want them on the happier side). Appropriateness would seem to factor as well – "Walking on Sunshine," for instance, might be a bad choice for a funeral home – though the research is scarce. A 1993 study in the Journal of Music Therapy found that fewer callers to a "protective services abuse hotline" hung up the phone when jazz was played, as opposed to "relaxation music."

But perhaps when it comes to appropriateness, hold music plays by its own rules. A 1999 study by a team of music psychologists solicited callers in response to a newspaper advertisement. When people called, they were simply placed on hold, in one of three conditions: music by The Beatles, "pan-pipe covers" of the same music, or a simple, repeating message. Curiously, the music that got them to hang on the line longest was not the Beatles but the pan-pipe covers – perhaps, the authors speculated, because it "was rated as corresponding more closely with callers' expectations concerning typical on-hold music". Or, per the earlier theory, the more familiar Beatles' tunes made the wait seem longer, thus callers hung up.

Over time, influenced by advances in other forms of queue management, hold technology has advanced. As with rides at Disney, we now expect estimated waiting times (people shown a wait time are up to two times less likely to "baulk," research has shown); companies such as Apple will even let you choose a time for a representative to call you back. A lot of wait time is sneakily siphoned off by interactive voice response systems ("press 3 if you are a calling about an international flight") There are even "tandem queues," for people with multiple issues ("I'll have to pass you off to my supervisor…"). Much maths and psychology goes into making this seem less painful. But at some point, we all have to face the music.

Sound science: why cats and the Rat Pack keep us on the line

Noting that the average British citizen will spend an hour of their life waiting in a queue, researchers Narayan Janakiraman, Robert Meyer, and Stephen Hoch sought to identify the factors that will persuade people to stay on line, and what will convince them to abandon calls completely.

Studies have found that as many as a third of callers who are put on hold when they contact a call centre will hang up and dial again primarily as a result of pure impatience. Tellingly, few benefit from such a strategy because they call back at some time in the future and their total cumulative wait time becomes much longer.

What can be done to mitigate these feelings? Some obvious answers would be to hire and train more phone staff or to reduce call wait times by analysing demand and capacity and then managing it more efficiently.

In their studies, Janakiraman and his colleagues tested an easily implemented small change that showed good results: Simply providing those in line with basic activities for them to engage in while waiting led to a significant reduction in dropped calls.

For example, financial institutions could provide customers waiting on hold with simple tips on money management via their automated voice system.

One person recounted a story of a customer who, on calling his mobile phone provider, was told by the customer service agent that her system was running slow and in order to save him from waiting, she would call him back later. Having already waited some time to get through, this customer wasn't going to give up the connection so easily and instead insisted that he stay on the line and wait.

"Very well Sir," replied the customer service agent, "if that's the case then perhaps you would tell me your favourite song." The customer was completely puzzled by such a random question but answered anyway. Imagine his astonishment when, having replied "'New York, New York' by Frank Sinatra," the customer service agent began singing it to him. The second example comes from our UK editor who told us that after calling the Cats Protection Agency he was put on hold, but rather than hearing music, he instead heard the soothing sounds of cats purring.

This is an edited extract from 'The smallBIG: small changes that spark big influence' by Steve J Martin, Noah J Goldstein and Robert B Cialdini (Profile, £11.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks