The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Want to master the art of being awake in a dream?

Lucid dreaming has become much more popular during lockdown. And people are eager to learn, control and prolong this dream state – but beware the charlatans, warns Steve Boggan

After a lifetime of admiring cheetahs, their grace and speed – yet knowing how deadly they could be – Emily Foster felt strangely unafraid when she came face to face with two of them. One had an injured leg and so she brought it food and water to ease its pain. The other was simply curious and attentive, and so she stroked and petted it, feeling the velvet lushness of its fur, hearing it purr, staring into its eyes.

Ahead of Emily was the glass wall of the cheetahs’ pen and there was a reflection of some text on it. She looked away and then turned to look at the glass again but this time the text was different. And this is when Emily realised she was having her first lucid dream – that is, she was aware and awake, inside the dream, as it happened.

“Everything was really, really clear and the colours were so, so bright and I knew I was in this dream and I was petting these beautiful animals and could look around and see how vivid it all was,” Emily recalls. “It was an amazing adventure. When I woke up, I was so excited – the adrenaline was so amazing. I just couldn’t sit still. It really is the best feeling you can imagine.”

Mastering the art – or, more precisely, the science – of lucid dreaming is not easy, but when they achieve it, lucid dreamers can exercise some control over their dreams. The most accomplished can travel at light speed to the stars, fly high above imaginary cities or live out their wildest sexual fantasies.

Sleep researchers estimate that 55 per cent of people have experienced lucid dreaming at least once but most would probably not know it was a recognised phenomenon. Increasingly, however, lucid dreaming is entering the public consciousness – not least during the pandemic, as bored and curious individuals look beyond Netflix for new diversions.

According to a recent article in WIRED magazine, Google searches related to lucid dreaming saw a significant spike during the first lockdown. Questions related to “How to lucid dream” increased by 90 per cent year on year.

More importantly, however, searches for “lucid dream mask” went up by 250 per cent and this is significant because there is a growing industry in neuroscientific gadgetry claiming to provide short cuts to lucid dreaming, and most involve some kind of mask. The problem is that while certain aspects of this technology are promising, much of it is questionable and researchers claim that some might be dangerous.

There is nothing new about lucid dreaming. Mystics and philosophers have embraced it for centuries. Aristotle is often credited with writing about it first in 350BC in a treatise entitled On Dreams in which he stated: “When one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which tells us that what presents itself is but a dream.”

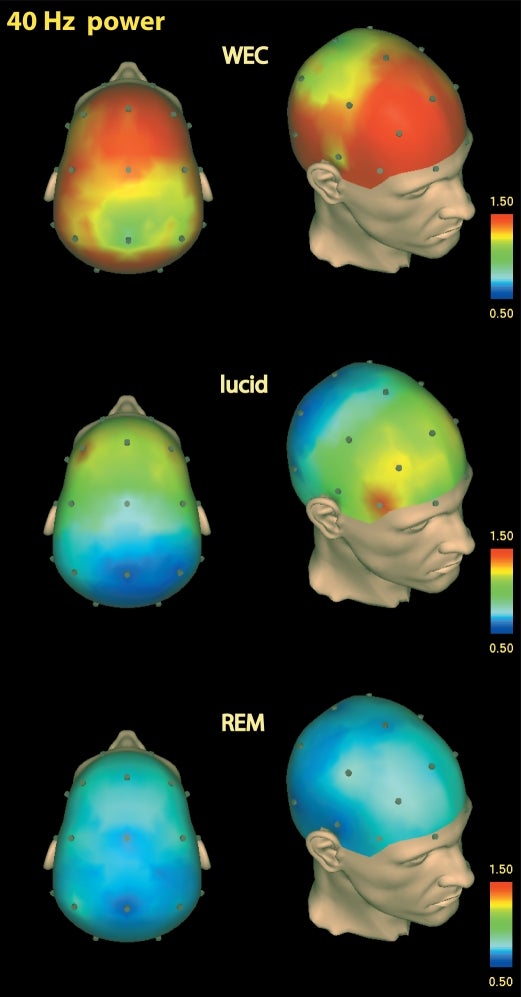

In 1968, in her book Lucid Dreams, the British philosopher and psychophysical researcher Celia Green postulated that lucid dreaming took place in the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleeping, one of the stages of sleep where brain activity is similar to wakefulness and where dreams are most intense.

She was proven right in an astounding experiment conducted by the psychologist Dr Keith Hearne in 1975 at Hull University. Using a piece of equipment called an electrooculogram (EOG), Hearne was able to record a pre-agreed set of eye movements signalled by an experienced lucid dreamer named Alan Worsley while Worsley was lucid dreaming in REM sleep. It was the first time one human being had communicated with another from inside a dream.

In an interview later, Hearne recalled: “It was like getting… signals from another solar system. I was ecstatic but had to keep quiet not to awaken the subject. It was an amazing, mind-boggling situation. I was looking at a communication from a person in another room who was asleep, unconscious, dreaming, yet in his own vivid world in which he was perfectly conscious and interacting with others.

It was like getting… signals from another solar system. I was ecstatic but had to keep quiet not to awaken the subject. It was an amazing, mind-boggling situation

“It was his reality. I was in my reality. A channel of communication had been established between those two realities.”

Hearne’s work was formally recognised and published in the journal of the Society for Psychical Research and subsequently replicated by other sleep researchers. His original ocular signalling chart recordings are on permanent display at the Science Museum in London. So, too, is his Dream Machine, a device he designed in the hope that it would help the subjects in his sleep laboratory to have lucid dreams.

This was the first machine of its kind but it was by no means the last. In the 1990s, the American psychophysiologist Dr Stephen LaBerge produced a device called the DreamLight, and since then, the trickle of lucid dream machines has threatened to become a torrent.

The Dream Machine and the DreamLight worked in similar ways, though the technology incorporated in the DreamLight was much more advanced. When a sleep lab subject was sleeping and dreaming in REM, the devices would alert them to the fact that they were in a dream, thereby making them “lucid” or aware of the fact. The Dream Machine gave them four mild electric shocks to the wrist – a sign which subjects had been told in advance represented four words: this – is – a – dream.

The DreamLight (which was later superseded by a device called the NovaDreamer) tried to induce lucid dreaming by shining lights from the inside of a sleep mask on to subjects’ eyelids during REM sleep. The idea was for subjects to realise that when they saw a light flashing inside their dream – from an imaginary streetlight or a passing car or a moonbeam – they were actually dreaming and so were made conscious of the fact, allowing lucidity to occur.

As well as light and electrical stimulation, subsequent devices used smell and sound to induce lucid dreaming, all with varying degrees of success.

In 2019, just a few months before the first cases of Covid-19 were diagnosed, a group of academics from the UK and Brazil published a paper entitled Portable devices to induce lucid dreams – are they reliable?’ which reviewed 10 pieces of equipment supposedly able to increase the probability of a person having lucid dreams. The academics took a critical look at the pioneering DreamLight and NovaDreamer along with newer models called Aurora, Remee, REM-Dreamer, ZMax, Neuroon, iBand, LucidCatcher, and Aladdin.

The best of these, the ZMax, at $900 (£660), is used in sleep laboratories around the world and utilises lab-standard technology to measure eye movement, brain activity, temperature, breathing and body movement, and for delivering light, vibrations and auditory stimulation. The cheapest, the Remee mask, at $65 (£48), simply has a timer that switches on flashing lights in the hope that its wearer is in REM sleep. This makes it too random for most researchers to take seriously. (I contacted the company that makes the Remee mask but received no response.)

The researchers found that the devices between these two ends of the spectrum either needed more tests, or lacked proof of efficacy, or were unlikely to reach the market because of their makers’ financial difficulties, or were providing electrical stimulation too low to be effective.

In terms of devices able to reliably induce lucid dreaming straight out of the box, I would say there is nothing at the moment

At the time the research report was published, May 2019, of the 10 devices examined, one was no longer available, one could be found only second-hand, four had yet to be released to the market, one could only be “pre-ordered” and just three were on sale. For anyone hoping to enjoy proven gadget-induced lucid dreaming, prospects were not good.

One of the authors of the paper, Achilleas Pavlou, a neuropsychologist and lucid dream researcher at the University of Essex, has since enjoyed promising results by using the ZMax in conjunction with his own research into individual volunteer’s sleep patterns. In his words he “figures out the optimal external stimulus method most likely to achieve success through the use of predictive machine learning algorithms” for the aspiring lucid dreamer and claims to be able to induce them in 55 per cent of cases – a very high success rate.

“There is a growing awareness of lucid dreaming because of films like Inception [where secrets are stolen or implanted by a thief able to access targets’ subconscious],” says Pavlou. “I think it is also becoming much more popular because of social media and the internet. Lucid dreaming is an experience and people are always on the lookout for new experiences.

“There is already a lot of wearable technology on the market measuring sleep patterns to help people improve the way they sleep – devices like [Google’s] Fitbit and the Dreem. But in terms of devices able to reliably induce lucid dreaming straight out of the box, I would say there is nothing at the moment. The ZMax provides a lot of the tools that sleep researchers need, but it requires specific programming and is probably too advanced for the ordinary consumer.

“People find the idea of choosing the dream they want to experience very appealing. This is why they will put their money into companies that go bust or buy into scams that tell them there is an easy way to lucid dream by just wearing a device. The truth is we are not there, but we are getting close. It is only a matter of time.”

The emerging clamour for lucid-dreaming short-cuts is evidenced by the amounts of money being raised by individuals and companies claiming to have them. For example, three of the devices examined in the paper co-authored by Pavlou were funded by money raised from the public on the Kickstarter platform.

iWink, the company behind the Aurora Dreamband, claimed it would make lucid dreaming “easy”. It raised $239,000 (£176,000) in 2013, promising the first devices would be delivered in February 2014. However, the latest update on its Kickstarter page, dated April 2018, says the company is taking “pre-orders” on its website, but the website no longer exists.

In 2017, Inteliclinic, the company behind the Neuroon lucid dreamer, raised $438,000 (£322,000) from almost 2,000 backers. A second Kickstarter campaign for a 450 euro (£400) “sleep tracker” has recently raised £356,000 from more than 2,000 backers. This, too, claims to promote lucid dreaming.

Last year, the $379 (£279) iBand+ Headband was launched following crowdfunding of more than £1m. Describing the device as an “EEG brain-sensing headband”, Arenar, the company behind it, promises unequivocally that it will “improve sleep and induce lucid dreams”, however, its website contains no reference to clinical trials.

Lucid dreaming is a complex skill, and like any other complex skill, it will take time and effort to master. Think of it as learning to playing a musical instrument

I contacted the companies behind the Aurora, Neuroon and iBand+ but none of them responded.

YouTube and the wider internet are full of gadgets, supplements and gurus all promising to induce lucid dreaming – in many cases Tonight! or In minutes! – but purists argue that there is no quick fix, no easy route into them.

Daniel Love – a renowned lucid-dream coach and author of the best-selling book Are You Dreaming? – is sceptical about lucid dreaming technology. When he isn’t flying around planets in his dreams (he is a keen astronomer), he devotes much of his time on his YouTube channel, the Lucid Dream Portal, calling out “charlatans” who make false claims about shortcuts and gadgetry that simply don’t work.

“Anyone promising lucid dreaming at all, promising it fast, promising shortcuts, is lying to you,” says Love. “There are no shortcuts to lucid dreaming at this point. It requires hard work. If you are new to lucid dreaming, don’t worry; it’s not that difficult. But it is nothing that can be turned on just like that.

“There are thousands of videos on YouTube that claim they can teach you to lucid dream, but most of them are over-hyped nonsense. Any video that claims you can lucid dream easily or lucid dream tonight or lucid dream in one minute or five minutes is being dishonest.

"Lucid dreaming is a complex skill, and like any other complex skill, it will take time and effort to master. Think of it as learning to playing a musical instrument. With the right training it will take most people between one to four months to experience their first lucid dream. To become a regular lucid dreamer takes more time and practice. On average, a year of intensive practice is the minimum required to get a real handle on the skill.”

Stephen LaBerge (the American sleep researcher who designed the DreamLight), identified two types of lucid dreams: wake-initiated lucid dreams (WILDs), and dream-initiated lucid dreams (DILDs). These describe the two entry points into a lucid dream. WILDs occur when a person falls asleep consciously entering into dream, so that the lucid dream initiates from wakefulness. DILDs occur when a person becomes aware are that they are dreaming while the dream is already under way, so lucid dreaming initiates from within the dream.

Love says there are “thousands” of unproven techniques to achieve WILDs or DILDs but he claims there are four core principles that have proven success:

• The keeping of a dream journal. This helps you to remember your dreams, become familiar with their nature, watch for patterns, and learn how they differ from waking life. If you’ve been writing about certain recurring dreams, this might help you to recognise one when you’re inside it.

• Performing regular “reality checks”. This involves one of any number of techniques that you perform regularly to check whether you are awake or asleep. For example, throughout the day, whenever anything unusual, illogical, or dreamlike occurs, pinch your nose and try to breathe. When you are awake, you can’t. But if the habit transfers into your dreams, where unusual and illogical events are common, and you pinch your nose in that dream, you’ll be able to breathe and will realise you’re dreaming. Another simple reality check is to critically observe your environment for anything unstable or nonsensical, such as text morphing upon a second read, digital clocks displaying a random or bizarre output, or environmental instabilities such as items changing colour, vanishing, or anything that would be impossible in waking reality. Emily says the changing of text in the reflection in the cheetah’s pen made her realise she was dreaming.

The funny thing about sex in lucid dreaming is that it doesn’t always go the way you plan just because you are lucid

• Interrupting sleep to increase awareness during the night, known as the Wake Back to Bed technique, though this is not recommended on a regular basis. Long-term disruption of sleep patterns can be unhealthy.

• Focusing on something while returning to sleep to maintain conscious awareness. This needs to be used alongside Wake Back to Bed or during any natural awakening. Most people have longer periods of REM during the last four hours of sleep, and so some lucid dreamers set an alarm during this period, wake up and get out of bed for roughly 20 minutes in order to increase mental focus, and then return to sleep to attempt to enter straight into REM sleep while being consciously aware that they are doing so.

These, and other of Love’s methods (here: https://bit.ly/38O8q8h), worked for 33-year-old Emily, who lives in Norway, after about two months of practice. That was in 2019. Since then, she has played with her cheetahs, flown high above skyscrapers and transported herself from apocalyptic dreamscapes into blindingly coloured interstellar nebulae. She once even met a very curious version of herself who kept asking questions; eventually Emily dismissed “herself” and watched as she disappeared into a Matrix-style wall of binary code.

Toni Porrello, a 35-year-old writer and yoga instructor from New York, says learning to lucid dream changed her life. She is now able to experience it two to three times a week.

“The moment of lucidity for me is like when you're watching a movie with a twist and you're like ‘OMG, the killer is HER? Now everything makes sense!’” she says. “And you start to see things differently, noticing all the signs you should have seen before, and your entire perspective shifts. Physically, things become brighter and your body feels light, but it is still so realistic, like you are in waking reality.

“One of my favourite things is eating while lucid dreaming. It's incredible what you can taste. I have eaten clouds, turning them into cotton candy, and I've eaten vegetables I don't like and made them taste like something I do. I've picked berries and tasted the sweetest berry you could ever imagine. It's really incredible.”

Lucid dreamers will tell you that they are most often asked about flying and having sex in their dreams, so I ask Toni if she has had experience of either.

“I have had many experiences with both,” she says. “The funny thing about sex in lucid dreaming is that it doesn't always go the way you plan just because you are lucid. There are always aspects of the unconscious working that aren't in your control. I have had funny situations where certain ‘parts’ didn't work. For example, I once unbuttoned a man's pants to find that he had nothing there – like a Ken doll.

“I seem to be more open to experience anything in lucid dreaming. Recently, I’ve been trying to feel what it's like to be man, and I was able to grow male parts. Then I realised that I wasn't attracted to women, so what do I do with said parts? Needless to say, I was literally caught with my pants down and ended up waking up.”

The most rewarding and beautiful thing you can get out of lucid dreaming is lucid living. Instant gratification would take this away entirely

Emily and Toni say learning to lucid dream involves dedication and practice and hard work. So, wouldn’t they have preferred to bypass the effort and simply let a machine switch them on to lucid dreaming?

“No,” says Emily. “The discipline involved and the things you learn along the way make your waking life more lucid, too. You become much more aware and appreciative of your surroundings and of yourself. The journey has made me a better person. I have always been painfully shy, but now I feel more confident, I’ve grown a thicker skin and am more at ease with myself.”

Toni agrees: “It would be a sad day the day there was a device that worked perfectly to do that because it would take away all the daytime practising and living lucidly, which is the true beauty in lucid dreaming. The most rewarding and beautiful thing you can get out of lucid dreaming, is lucid living. Instant gratification would take this away entirely.”

Several lucid dreaming experts I spoke to said they had concerns over devices worn on sleepers’ heads, not least, because they are powered by various types of lithium batteries, and some concerns have been raised over these. The US-based National Fire Protection Association says of them: “Like any product, a small number of these batteries are defective. They can overheat, catch fire, or explode.” And while this is highly unlikely to happen where devices are responsibly charged, one mishap would be one too many.

Perhaps the last word on lucid dreaming devices should go to the man who made the first one: Dr Keith Hearne. I asked him if modern versions of his Dream Machine could transport the masses into lucid dreaming.

“In all laboratory experiments, there is a huge psychological effect," he says. “In my research, some control subjects who were wired up to the Dream Machine dreamt that they felt the four pulses to the wrist, indicating ‘this – is – a – dream’, and they would say: ‘I felt the pulses and I became lucid’. The problem was that some of these were hooked up to the machine when it wasn’t switched on. So, for them, an empty box that had a few lights and switches would have worked.

“These devices are paradoxical. They aren’t like washing machines that either work or don’t work. These cannot work, and yet work because of the psychological effect, so we can’t be too scathing of them if they work indirectly. The empty box with switches and lights would work for quite a lot of people in inducing lucid dreams. And the more expensive a device is, the more likely some people would be to convince themselves that it will work – and it might work … even if it doesn’t work in the way it was intended.”

And if all this feels rather like trying to catch a butterfly with a thimble, then maybe it is. One thing seems certain, at least for now. If you think you can cross into the world of lucid dreaming – guaranteed – every time you slip a piece of gadgetry on to your head, then perhaps it’s time for another reality check.

Emily Foster is a pseudonym

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks