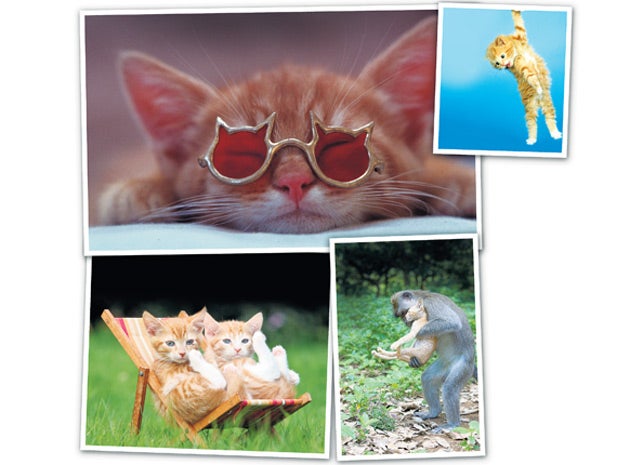

Memes: Take a look at miaow

What links silly cat pictures and Richard Dawkins? Jean Hannah Edelstein meets the academics trying to understand our love of internet 'memes'

Kate Miltner is a fan of lolcats – pictures of cats with daft captions. A big fan. A super fan, even. "I dressed up as a lolcat for Hallowe'en in 2008," she explains. "I was Happy Cat and my boyfriend at the time was a Cheezburger [after the website home of lolcats – I Can Has Cheezburger], and we attached huge-impact font letters to ourselves – I can send you a picture if you want."

But this fancy-dress outing didn't fully satisfy Miltner's interest in the online photos of scampish kittens with annotations in the intentionally stupid dialect known as "lolspeak".

Instead, Miltner decided to follow her passion across the Atlantic from New York, where she'd worked in advertising and digital strategy, into the lecture halls of the London School of Economics. The 29-year-old has just handed in her dissertation to complete the requirements for her MSc from the university's Department of Media and Communications. The focus of her study? Internet memes, ie, often trite, viral images and films. More specifically, her favourite furry ones. Provided she makes it past the examiners, Miltner will soon be qualified to say "I can has master's degree", having completed a qualitative audience study of lolcat users.

Academics working in more classical disciplines may be inclined, well, to LOL at the prospect of her investigations. But Miltner is among a growing cohort of pioneering researchers to be heralding the study of internet memes as a field of legitimate academic enquiry.

And why not? Miltner and her cohorts – such as Patrick Davison, a 28-year-old candidate at the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, and Cole Stryker, a 27-year-old author of a forthcoming book on the memesphere – were once among the first teenage adopters of the web. "The short answer [to why meme research is important] is because these are the kind of cultural interactions that people participate in these days," Davison says.

He was collaborating on independent meme research with New York groups such as Know Your Meme and MemeFactory before he decided "that graduate school would afford me substantially more resources" to do the work he was interested in. "You wouldn't blink twice if someone said they wanted to study the cultural effect of newspapers or books or TV," he says.

Images of gambolling kitties – sorry, "kittehs" – were not what Richard Dawkins had in mind when he coined the term "meme" in The Selfish Gene to describe the application of evolutionary frameworks to the exchange and development of culture in the form of ideas, trends, and behaviour. "Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catchphrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches," Dawkins wrote in 1976. So the study of memes (in case, like many people, you've mainly only seen the word written on a screen, it's pronounced "meems"), a discipline known as mimetics, is not actually new.

But "the term has been hijacked to refer to goofy iconography" in mainstream culture, Stryker explains to me when I speak to him (on Skype, of course).

Stryker's book, Epic Win for Anonymous: How 4chan's Army Conquered the Web, will be published in the UK by Duckworth in November, and it goes deep into the underpinnings of the somewhat notorious 4chan social website: birthplace of the marauding hacking group Anonymous, but also of those adorable kittehs, among other memes.

Stryker is primarily a blogger and isn't associated with a university – "I think that casual bloggers are more interesting than media studies professors" – but Miltner advises me that "he knows the memesphere like no other", and one critic on the social blogging platform Tumblr describes him as "A STRAIGHT UP G", which sounds promising.

Meme research began to flourish, Stryker explains, "around the late 1990s or early 2000s" when "people in the web-content industry were trying to figure out what this new form of culture was all about". He credits Jonah Peretti, the co-founder of The Huffington Post and now founder of BuzzFeed, for making "meme" the working term for viral web content.

Peretti is also behind the key "bored at work" theory – in a nutshell, that a driving factor in the propagation of meme culture is that it gives people short, pleasant bits of entertainment, in contrast with the tedium of the workday. "Any kind of art is alleviation of boredom," Stryker says. "But I think that memes specifically are so prevalent because you have an entire workforce that is tied to a computer in a cubicle... The cost of participating in the memesphere is very low. And... companies are realising it's almost necessary for the workforce" as, he believes, an alternative to "a bullet in the head".

Miltner cites a list of examples that demonstrate what Davison describes as "the growing bleed between web culture and mainstream culture". "Cheezburger Networks, which publishes a collection of websites that focus on different memes, just received $30m in venture funding. People have translated the Bible, Shakespeare and TS Eliot into lolspeak." She is less interested in whether lolcats are what Clay Shirky called "the stupidest possible creative act" and more in why they've struck a chord with audiences. "The way that people share lolcats is different from the way that 'sharing' as a practice/behaviour has been contextualised in the literature thus far, which usually focuses on satisfying self-oriented needs like identity construction and recognition. With lolcats, it was very personal and altruistic."

Stryker also cites personalisation as a key way in which memes differ from other pastimes. "Memes represent a fundamental shift in the ways that humans are communicating," he says. "More so in the way that they are experiencing entertainment... [Memes] bode well for the future of artistic expression, that so many young people are equipped with the tools to not just create culture." "Did people like coming up with, spreading, altering, and laughing at silly insider jokes before the internet?" Davison asks. "Absolutely." The difference is mediation: "made possible by computers, and the incredible speed of transmission made possible by the web".

Miltner's research, which she conducted using a series of focus groups in London, reflects this. "The participants in my groups did mention that the digestibility of lolcats (and memes in general) makes them a good workplace distraction because it doesn't require a great deal of time investment," she says. "To quote one of my participants: 'It's really about the pleasure of seeing the funny picture, reading the cute caption, being satisfied, and then getting back to whatever I'm doing.'"

"To be honest," Miltner continues, "I think that's one of the reasons that they're kind of discounted as having any import – people think 'silly cat picture'." But she refutes this through citing Henry Jenkins – Professor of Communication, Journalism and Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California – who qualifies memes as being "spreadable media": that is, to mutate and transform as they pass through networks, rather than emanating from a central distribution point.

Davison is also quick to dismiss potential detractors of the field. "I think one of the nice things about memes is that they unseat traditional notions of significance," he says. Davison is particularly interested in the development of new research frameworks to process the evolving forms of meme data. "I wrote a paper last term about the challenges presented by attempting to perform a a cultural analysis of YouTube comments," he says. "The researcher who wants to make sense of these comment threads has to be equally savvy in database design as they are in hermeneutics [the study of interpretation]."

Meme researchers may be studying what people are doing when they're messing around, but they're not messing around themselves. "The fact is," Davison says, "it's important to study the cultural interaction people perform when bored because that's when they're performing them. If people only used the internet when they were horny, then we'd be talking about that. But that's not the case. At least, I don't think."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks