Age verification checks for porn sites aren’t working – but there’s a way to fix it

Video games and VPNs are allowing people to easily circumvent the Online Safety Act, with experts blaming a complete lack of trust. There may be a better way to enforce it, Anthony Cuthbertson writes, and it has the backing of child safety charities and adult sites alike

It took until 10am on the day when the UK’s new online age checks came into force for people to figure out an absurd workaround. The rules brought in by the Online Safety Act meant that websites hosting pornographic or adult content were required to “robustly” age-check users, with one popular method being a facial recognition tool that estimates a person’s age from a picture of their face.

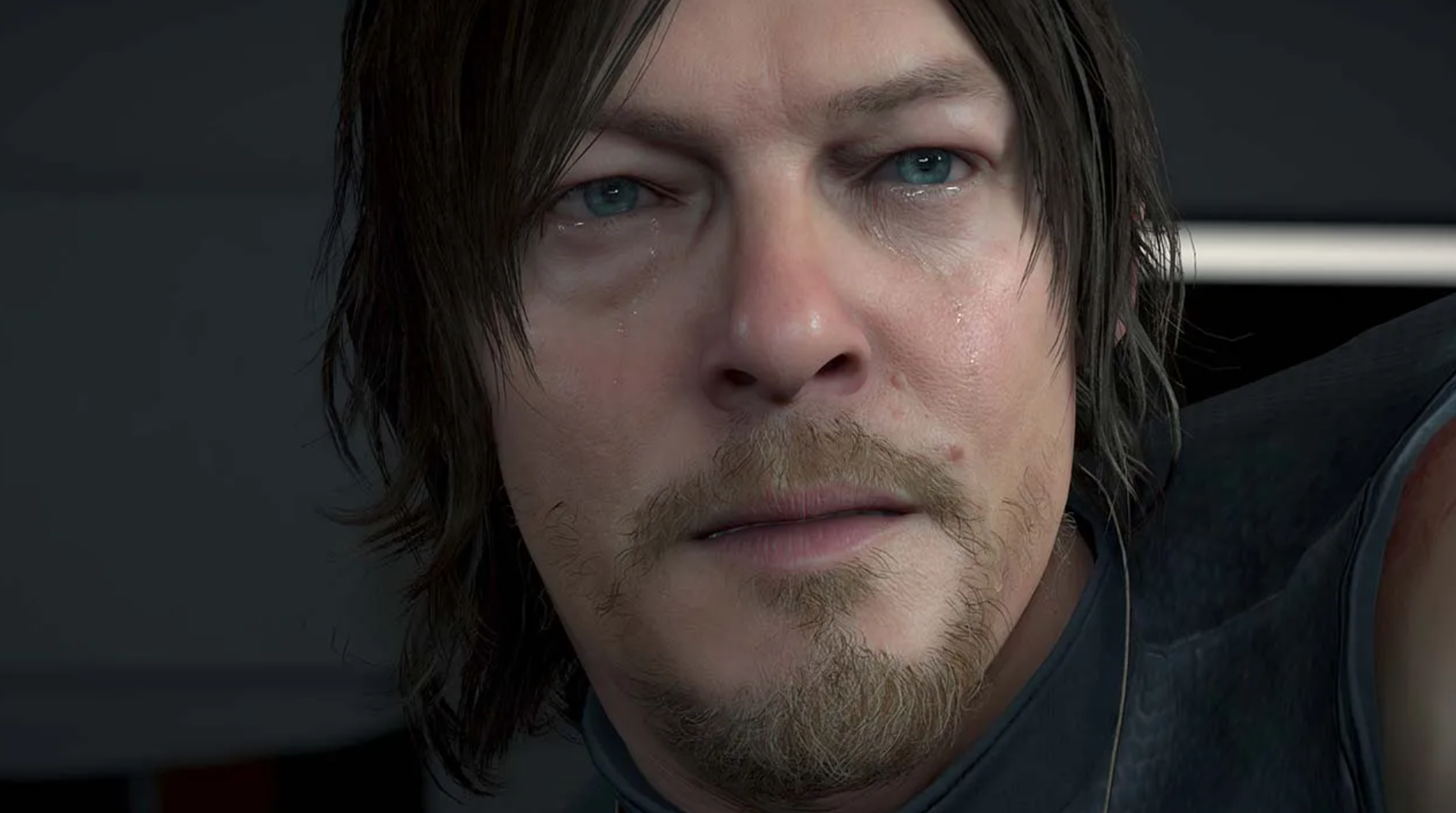

One way to bypass this, it soon transpired, was to fool the software by using an image of a character from a video game. The photo-realistic protagonist of Death Stranding was enough to allow visitors to skirt past the barriers set up by third-party face-scanning systems Persona and k-ID, which were used by Reddit and Discord.

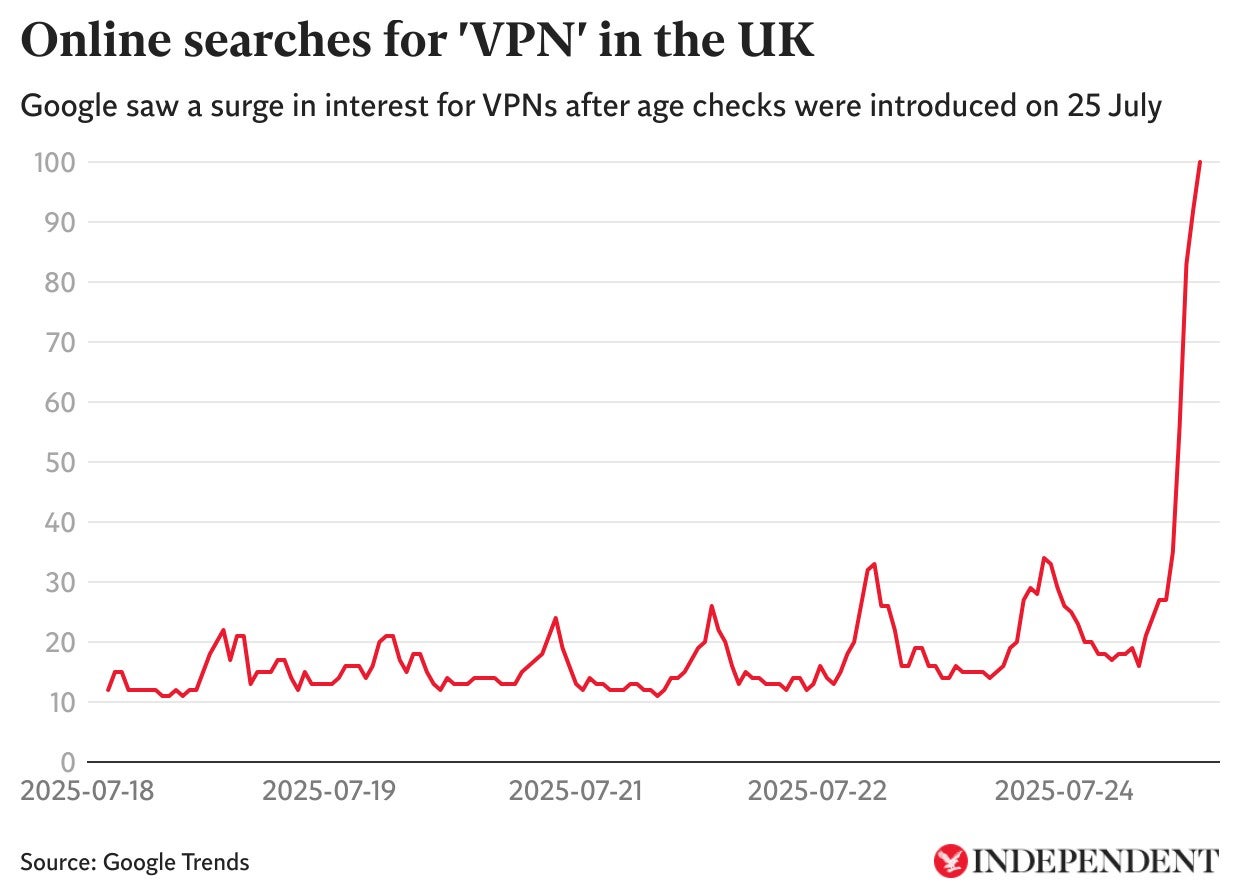

It was not the only way to bypass the newly restricted parts of the internet. There was a sudden surge in demand for virtual private networks (VPNs), as web users sought to spoof their device’s location to countries without the web restrictions.

VPN review site VPNMentor observed a 6,000 per cent increase in demand after the law came into effect last Friday. The company noted that this trend raises critical questions about the effectiveness of the measures designed to protect children’s online safety, as well as the risks involved in complying with them by submitting photos, ID documents or financial data.

When similar laws came into force across more than a dozen US states, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) warned that online age verification exposed every website visitor to privacy and security dangers.

“Records of our personal information tied to details of the adult content we watch, sexual questions we have, or interests or identities we’re exploring could make millions of people vulnerable to harassment, blackmail and exploitation,” Antonio Serrano, advocacy director at the ACLU, said in January.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights advocacy group, has also claimed that this exposes people to hackers and bad actors who might misuse the data for marketing purposes.

The rise in VPN downloads since the UK’s age verification rules came into force has highlighted this mistrust when it comes to sharing personal information in order to access adult websites.

“The issue is psychological as much as technological. It’s trust,” Alex Laurie, a senior vice-president at security platform Ping Identity, tells The Independent.

“People are more comfortable handing over credit card details to gambling sites than sharing personal data to access adult content – even when trusted, third-party verifiers handle the checks and the sites never see the data. Rebuilding trust means rethinking verification entirely.”

The alternative approach would involve placing age restrictions on each individual smartphone, tablet and computer. This would block minors from viewing adult content, while also negating the need to adopt other drastic measures, like banning VPNs entirely.

It would place the onus on multibillion-dollar tech firms such as Apple, Google and Microsoft, who build the operating systems these devices run on, rather than individual websites that may not have the budget or resources to comply with the new regulations.

While primarily aimed at pornography sites, the sweeping blocks have affected everything from hobbyist forums to community support groups on Reddit related to periods, sexual assault and quitting smoking.

Visitors to one electric vehicle forum are no longer able to access the site after its operators chose to block access from the UK rather than risk a hefty fine. Outraged at such consequences of the new law, nearly half a million people have signed a petition to repeal the Online Safety Act, claiming that it is “far broader and [more] restrictive than is necessary in a free society”.

The Wikimedia Foundation, the non-profit organisation behind Wikipedia, has launched a legal challenge against technology secretary Peter Kyle, claiming that the Online Safety Act could force it to verify adult contributors. It contends that this could put its volunteers at risk of “data breaches, stalking, lawsuits, or even imprisonment by authoritarian regimes”, according to a filing with the High Court.

Kyle has described the Online Safety Act as “the biggest step forward in safety since the invention of the internet”, despite the apparent ease with which its provisions can be circumvented. He also dismissed calls to make VPN services illegal, saying that the government is “not considering a VPN ban”.

VPN technology is not primarily designed to access geo-restricted content; rather, it encrypts internet traffic to protect web users from hackers, cybercriminals and government surveillance. Protesters in Turkey have used VPNs to communicate during state crackdowns on social media, while Iranian citizens use them to access Western news outlets and bypass bans on messaging platforms.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, searches for VPNs spiked in occupied regions as Ukrainians sought to coordinate digital resistance without being detected.

While Kyle has dismissed the idea of an outright ban on VPNs, he did say the government would be looking “very closely” at how they are being used. Ofcom has also indicated that it is “assessing compliance” with the new regulations, but neither has mentioned the possibility of device-based age verification. The Independent has reached out to Ofcom for comment.

The proposed system involves a one-time age check through the device’s operating system, with the user’s age then securely stored on the device. Among its advocates is the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children, who put forward the idea in the Digital Age Assurance Act Legislation in 2024.

The device-based approach is also favoured by many of the sites that already have the current age checks in place.

“Keeping minors off adult sites is a shared responsibility that requires a global solution – requiring cooperation between government, tech platforms and adults,” a spokesperson for Aylo told The Independent.

“We continue to believe that to make the internet safer for everyone, every phone, tablet or computer should start as a kid-safe device ... This is the core premise of device-based age verification, which we believe is the safest and most effective option for protecting children and maintaining user privacy online.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks